Daniel 6:1–28; Additions to the Book of Daniel: Bel and the Dragon 14:31–42

Daniel in the Lions’ Den

Unknown artist

Daniel in the Lion's Den, 3rd century, Wall painting, Anonymous Catacomb of via Anapo, Rome; akg-images / De Agostini Picture Lib. / V. Pirozzi

Daniel under Persecution

Commentary by Sung Cho

Christian iconography may have existed since the emergence of Christianity, but no extant images precede the third century.

Key to establishing this as the earliest point in the chronology was Antonio Bosio’s 1578 discovery of the third-century catacomb on Via Anapo in Rome. The anonymous cemetery consists of a main gallery opening onto shorter secondary branches with cubicles and niches. One of the five frescoed cubicula distinguishes itself with depictions of Jesus alongside the Old Testament figures of Noah, Moses, and Daniel.

In this wall painting, Daniel stands nude with arms raised as if in mid-prayer. Typologically, this posture may also signify Christ crucified. Though his visage is effaced, his physique suggests vigour, despite the biblical account narrating this event as taking place late in his life. The equivalent work in the fourth-century catacombs of Marcellinus and Peter does preserve Daniel’s face intact, and it is indeed youthful.

On both sides of Daniel are lions looking up at him submissively. The man dwarfs the beasts so that they are reduced to the size of domestic pets, more or less knee-high. The background is minimal and streaked with brown, enough to suggest a den or a cave.

While this work may belong to the infancy of Christian art, it adds much value to understanding an epoch. The date of its creation is near the decade of the Decian and Valerian persecutions of the 250s. The Christian communities of Rome could see parallels in the faithful Daniel who also faced trouble from authorities.

It is also helpful to contextualize this wall painting in its cubiculum. As it stands among reminders of God’s provision (the Good Shepherd, the miracle of the loaves, Moses bringing forth water from the rock) and his power over death (Raising of Lazarus), it also communicates the power of prayer for protection.

References

Croix, G. E. M. de Sainte. 2006. Christian Persecution, Martyrdom, And Orthodoxy, ed. by Michael Whitby and Joseph Streeter (Oxford: Oxford University Press)

Killerich, Bente. 2015. ‘The State of Early Christian Iconography in the Twenty-first Century’, Studies in Iconography 36:99–134

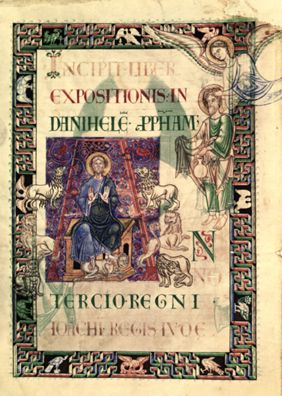

Unknown artist, School of Citeaux

Daniel in the Lion's Den fed by the prophet Habakkuk, from Saint Jerome’s ‘Explanatio in Prophetas et Ecclesiastes’, Early 12th century, Manuscript Illumination, Bibliotheque Municipale, Dijon; MS 132, fol. 2v, akg-images / Erich Lessing

All Things Under his Feet

Commentary by Sung Cho

The commentaries of Jerome, dating back to late fourth and early fifth centuries, are key milestones in the history of Christian biblical exegesis. His works on the Old Testament, such as the expositions of Ecclesiastes and the prophets, are especially noteworthy. Jerome displays his scholarly erudition, explaining in Latin the relevant Hebrew, Aramaic, and Greek sources.

Jerome’s treatment of Daniel 6 is typical of this approach as he explores certain words and phrases like ‘upper room’ in verse 10. As for Daniel 14, one of the Greek additions to the book, he only comments on verse 18 as there is no underlying Hebrew or Aramaic text.

Jerome’s commentaries on the Prophets and on Ecclesiastes are preserved in an early twelfth-century Burgundian work. It contains a visual representation of Daniel in the lion’s den. To the right of Daniel, and in mid-air, is the angel lifting Habakkuk by his head as he carries sustenance to the prophet, as recounted in 14:31–42. Daniel himself sits (v.40) with his hands raised in prayer. He is surrounded by six lions, three on each side of him.

The seventh lion (v.32), prostrate directly beneath Daniel and serving as his footstool, deserves the most attention. This central placement of the subdued lion beneath Daniel evokes images of humankind as the viceroy of God over creation. This evocation of the royal role of the human relates the image simultaneously to the past, to the future, and to the present.

First, a connection is made to the intended order of creation at its very beginning (Genesis 1–2; Psalm 8:6): humanity exercising dominion over all things. Next, as it relates to the future, Daniel also prefigures Christ who takes his seat in heaven as his enemies are made his footstool. Eventually, all will be subject to him, even the last enemy, death (Psalm 110:1; 1 Corinthians 15:20–28). Finally, there is the most obvious direct link to Psalm 91:13 which comforts and emboldens all who take refuge in God in the here and now: ‘You will tread on the lion and the adder, the young lion and the serpent you will trample under foot’.

References

Archer, Gleason L. (trans.). 2009. Jerome's Commentary on Daniel (Euguene: Wipf and Stock)

Fretheim, Terence E. 2005. God and World in the Old Testament. A Relational Theology of Creation (Nashville: Abingdon)

Unknown Armenian artist

Daniel in the Lion's Den and the Three Youths in the Fiery Furnace, 915–21, Stone relief, Holy Cross Church, Aght'amar, Turkey; akg-images / Erich Lessing

Even the Lions Submit to Him

Commentary by Sung Cho

Located on Aghtamar Island, in eastern Turkey’s Lake Van, is the Cathedral of the Holy Cross. It was one of various construction projects of Gagik I Artsruni, who reigned over the kingdom of Vaspurakan during the first half of the tenth century. It served the purposes of the Armenian Apostolic Church, was later the seat of the Catholicosate of Aghtamar, and more recently has become a museum attraction.

The portrayal of Daniel 6 in the relief of the eastern façade is notable for multiple reasons. First, this story rarely appears in Armenian written sources, as the prophetic material in Daniel received more attention than its narratives.

Second, left of it is the trio of Shadrach, Meschach, and Abednego from Daniel 3, facing and surviving the ordeal of the fiery furnace. They stand shoulder to shoulder and pray with hands raised like Daniel.

Third, the artist harmonizes parts of Daniel 6 and 14. Above Daniel are benefactors arriving to help him, based on the Greek addition to Daniel (in particular, here, Daniel 14:31–42). In the later passage, as a consequence of defeating Bel worshippers and the dragon (Additions to Daniel: Bel and the Dragon), Daniel is again thrown into the lion’s den. While imperilled, the prophet Habakkuk makes a cameo appearance, bringing Daniel food originally intended for reapers in Judea. He covers the great distance and locates the den in Babylon speedily because the angel of the Lord takes him by his head and carries him by his hair.

Fourth, below Daniel are two lions on both sides of him. As expected, the beasts submit to the man, but their servility is heightened here. Instead of looking up at Daniel, they are inverted with their heads down, licking his feet. The earliest extant evidence of this tradition comes from a third-century text (ex. Hippolytus of Rome, Commentary on Daniel 3.29.3). In this, Hippolytus accentuates themes from Daniel which evoke hopes of the resurrection and of a restored created order as the lions submit to Daniel, a type of the second Adam (1 Corinthians 15:42–49).

References

Dulaey, Martine. 1998. ‘Daniel dans la fosse aux lions: Lecture de Dn 6 dans l'Église ancienne’, Revue des sciences religieuses 72: 32–50

Schmidt, T. C. 2022. Hippolytus of Rome’s Commentary on Daniel, Gorgias Studies in Early Christianity and Patristics 79 (Piscataway: Gorgias)

Thompson, Robert W. 2019. ‘Armenian Biblical Exegesis and The Sculptures of the Church on Ałt‘amar’, The Church of the Holy Cross of Ałt‘amar Politics, Art, Spirituality in the Kingdom of Vaspurakan, ed. by Zaroui Pogossian and Edda Vardanyan, Armenian Texts and Studies 3 (Leiden: Brill)

Unknown artist :

Daniel in the Lion's Den, 3rd century , Wall painting

Unknown artist, School of Citeaux :

Daniel in the Lion's Den fed by the prophet Habakkuk, from Saint Jerome’s ‘Explanatio in Prophetas et Ecclesiastes’, Early 12th century , Manuscript Illumination

Unknown Armenian artist :

Daniel in the Lion's Den and the Three Youths in the Fiery Furnace, 915–21 , Stone relief

Key Constants

Comparative commentary by Sung Cho

Daniel 6 closes the first of two or three major sections of the book. Chapters 1–6 contain tales of kings, of Daniel, and of Daniel’s friends.

There are bewildering complexities in Daniel. They include its languages (Hebrew, Aramaic, and—in the additional material—Greek) and its prophetic/apocalyptic content (mostly in the second section, chapters 7–12, but not limited to that). Against this background, the story of Daniel in the lion’s den in chapter 6 stands out as a straightforward narrative account.

As he did with Chaldean kings, Daniel serves Darius the Mede and distinguishes himself in kingdom administration. Jealous rivals trick Darius to enforce an ordinance that requires all to pray to the king on pain of death—i.e. violators are thrown into the lion’s den (6:7–9). As anticipated, Daniel does not waver from his discipline of prayer and Darius is forced to execute Daniel. Daniel survives the night and testifies that God sent his angel to protect him. The king retrieves Daniel, throws his accusers into the den, and decrees that Daniel’s God be revered.

There is a similar story in the Greek supplementary material of Daniel. In chapter 14, Daniel convinces Cyrus that Bel and the dragon are mere idols and not living gods like his true God. The Babylonians threaten the king and his household, force him to hand over Daniel, and throw him into the lion’s den for seven days (14:29–31). Once again, the lions do not harm Daniel. Also—to sustain him during that week—the angel of the Lord speedily transports Habakkuk from Judea to Babylon, carrying him by the crown of his head. In the hand of the prophet are stew and bread originally intended for reapers, now given to Daniel. Again, Daniel emerges from the den, his king rejoices, and his enemies are fed to the lions. Common themes of piety and persecution as well as overlaps in their details have facilitated harmonization of the two stories in visual representations.

The key constant in the two accounts is Daniel’s confrontation with ravenous lions. This image of devotion has had ubiquitous appeal across different religious traditions (Jewish, Christian, Islamic, Hindu) in various parts of the world. With minimal changes, artists who depict this scene have been able to communicate profound truths in visual form.

Christological themes have been particularly evocative in the Church’s traditions of interpretation. For example, in Demonstrations 21.18, Aphrahat (c. 280–367 CE) likens Daniel’s enemies to the enemies of Jesus; the lions’ pit to the pit of Sheol; and the grief of Darius to the grief of Pilate. Other overlaps include the shaming of Daniel’s and Jesus’s enemies after the two men’s respective vindications.

As for visual commentaries, pre-Constantinian Roman Christians in the Catacomb in the via Anapo could see in the figure of Daniel a model of Christ-like suffering and prayer as he raises his arms in a cruciform pose. Also appealing to Christian readers have been the Psalmist’s references to his enemies as lions in Psalm 22 (vv.12–13, 19–21) since Jesus cites the first words of this psalm on the cross (see also Psalm 7:1–2; 17:12; 35:17; 57:4; 58:6).

The link between Daniel and Christ is made not just in connection with the Crucifixion, when Jesus was, like Daniel, encircled by his foes. When works of visual art show us the ferocious beasts now making obeisance to the triumphant hero, as they do in the façade relief on the Aghtamar Cathedral of the Holy Cross, they anticipate post-resurrection scenes. Just as the risen Jesus receives worship from those who take hold of his feet (Matthew 28:9), Daniel receives honour from the beasts who kiss his feet.

Finally, there are anticipations of Christ on the throne. The twelfth-century artist of the Burgundian St Jerome’s Commentary on the Prophets and Ecclesiastes is careful to employ details from Daniel 14 in its description of the later ordeal with Cyrus, rather than the earlier one with Darius which occurs in Daniel 6. The later account states that Daniel ‘sat’ and ‘seven lions’ were in the den. The humiliation of the seventh lion in being used as a footstool may have encouraged believers to anticipate a time when all enemies would be placed beneath Christ (1 Corinthians 15:25; Ephesians 1:22; Hebrews 1:13; 10:12–13).

References

Newsom, Carol A. 2014. Daniel: A Commentary (Westminster: John Knox)

Commentaries by Sung Cho