Daniel 3; Additions to Daniel: The Prayer of Azariah and the Song of the Three Jews

The Fiery Furnace

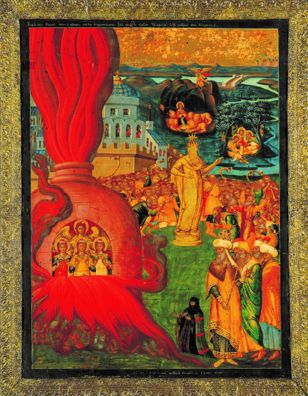

Konstantinos Adrianoupolitis

The Story of Daniel and the Three Youths in the Fiery Furnace, Second half of 18th century, Icon, 63 x 48 cm, "Benaki Museum of Greek Culture, Athens; ΓΕ 3034, © 2020 Benaki Museum, Athens

In the Shelter of the Most High

Commentary by Peter S. Hawkins

This eighteenth-century icon by Konstantinos Adrianoupolitis gives a highly detailed rendition of Daniel 3. In the left foreground we see an immense furnace, its flames soaring beyond the picture’s borders. Inside are the three young Hebrews, identical, with their arms extended in thanksgiving and prayer—figures of undaunted piety. Close behind them is an angel embracing them with his protective wings; in front of them, overcome with an overflow of fire, are the Babylonian servants who consigned the Hebrews to the flames.

To the right of centre is the golden statue erected by the emperor; at the lower right Nebuchadnezzar is juxtaposed with his idol and flanked by courtiers in sumptuous garments and headgear. Crowds of men meant to represent ‘all the peoples’ focus their gaze intensely on the idol, which is serenaded by an orchestra of horn, pipe, lyre, trigon, harp, drum, ‘and every kind of music’ (Daniel 3:7). While the multitude turns from all directions to worship the golden statue, Nebuchadnezzar is fixated on the men within the blazing furnace. They look directly at the viewer with the same serene smile we see on the angel’s face.

Konstantinos Adrianoupolitis might well have left it at that; instead, he gives us an abundance of detail beyond what is offered by the Scriptures. City dwellers jam the ramparts to take in the spectacle below them. Painterly images of the ‘works of the Lord’ (Song of the Three Jews 35; Daniel 3:57 LXX), mountains and a river, limn the horizon. A figure in monastic garb—presumably the icon’s donor—kneels in front of the emperor so as to look beyond him, to venerate the faithful Hebrews in the furnace.

The painter also places Daniel 3 within a wider narrative. In the distance at the upper right of the composition, we see the prophet Daniel called to vision by an angel; below, he is shown in the lion’s den, its ravenous beasts smiling broadly at the holy man who crosses his hands in prayer. Beneath that vignette and to the right, we see the three young Hebrews studying a scroll of Scripture and surrounded by stringed instruments of praise. It is as if they are preparing for the Benedicite that they will later sing in the furnace: ‘Give thanks to the Lord, for he is good, for his mercy endures forever’ (Song of the Three Jews 67; Daniel 3:89 LXX). A fragment of that Song is inscribed in the upper border of the icon, calling the viewer to thanksgiving as well.

Unknown artist

The Three Hebrews in the Furnace, c.250–300 CE, Fresco, Catacomb of Priscilla, Rome; Scala / Art Resource, NY

A Baptism of Fire

Commentary by Peter S. Hawkins

Found in the third-century Roman catacombs of Priscilla, this paleo-Christian wall painting shows the three young Hebrew men of Daniel 3 thrown into a fiery furnace by the Babylonian emperor Nebuchadnezzar. Their crime was refusing to worship an immense golden idol traditionally thought to represent the monarch himself.

Whereas the biblical account is full of detail, the mural is selective in what it shows. It gives us the faithful believers—Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego—but only a suggestion of the furnace flames and nothing of the servants who commandeered them, the courtiers who gathered to watch their incineration, or the emperor who ordered it. Instead, the focus is on those who risked death trusting in God for deliverance; who, even if martyred, vowed to obey the prohibition of the first commandment (Exodus 20:3):

Be it known to you, O king, that we will not worship your gods nor adore the golden statue which you have set up. (Daniel 3:18 NRSV)

Interest in the Hebrews extends to their exotic clothing, which is itemized in Daniel 3:21. Although the exact meaning of the terms is debated, they are rendered in translation as tunics, trousers, hats, and ‘other garments’. Attention is also paid to their erect posture, open hands, and extended arms uplifted in the orant or prayer gesture. Might they together be singing the Benedicite thanksgiving hymn found in the Greek addition to Daniel 3 (Song of the Three Jews 23–68; Daniel 3:51–90 LXX).

The figures radiate a sense of calm, as if confident of their rescue. The fire in which they stand poses no apparent danger: it appears more like garden foliage than flame. Above them hovers a dove bearing an olive branch, perhaps a visual reminder of the Noah story and its deliverance (Genesis 8:11). In Daniel there is a fourth figure in the fiery furnace, who has (according to Nebuchadnezzar) ‘the appearance of a God’ (Song of the Three Jews 25; Daniel 3:92 LXX); here, however, that protective divine presence, otherwise taken to be an angel or Christ, suggests the Holy Spirit, who at Jesus’s baptism descends from heaven ‘like a dove’ (Matthew 3:16; Mark 1:10; Luke 3:22).

References

Walton, Ann. 1988. ‘The Three Hebrew Children in the Fiery Furnace’, in Medieval Mediterranean Cross-Cultural Contexts, ed. by Marilyn J.Chiat and Kathryn L. Reyerson (St. Cloud, MN: North Star Press of St. Cloud), 57–66

Unknown artist, France

Censer depicting the Hebrews in the Fiery Furnace, c.1160–65, Cast brass, chiselled and gilded, h. 16 cm; d. 10.4 cm, Palais des Beaux Arts de Lille; A 82, Photo: Stéphane Maréchalle, © RMN-Grand Palais / Art Resource, NY

Let my Prayer be Counted as Incense

Commentary by Peter S. Hawkins

Although the story of the three young Hebrews in the fiery furnace is a familiar trope of divine deliverance, its iconographic use on a censer seems to be unique. This mid-twelfth-century spherical incense burner, made for use in the liturgy, is a masterpiece from the Moselle valley in France. Its two hemispheres are decorated with dense foliage and fantastic creatures. An angel or perhaps a figure of Christ crowns the censer’s summit, seated on a pedestal and offering protection; below him, in a circle, sit the three Hebrews, each of whom is named by an inscription below his image, and each of whom strikes a distinctive pose. Here, as in the Greek addition to Daniel 3, it is Abednego (named Azariah) who alone is shown in the orant posture of thanksgiving, for it is he who stands in the fire and prays aloud, ‘Blessed art thou, O Lord, God of our fathers… (Prayer of Azariah 3; Daniel 3:26 LXX).

This emphasis on individuality is reinforced by a first-person Latin text that runs across the circumference:

I, Rénier, give this censer a sign so that at the hour of death you may grant me a funeral similar to yours, and in the belief that your prayers will rise like incense to Christ. (trans. by Palais des Beaux Arts de Lille)

Scholars speculate variously that this Rénier may have been a donor, the artist himself, or perhaps someone who both made and gave the work to a monastic community (Gearhart 2013). The gift’s stated purpose is to signify his salvation, offering prayers to help him to, as the inscription says, ‘rise like incense to Christ’.

With smoke issuing forth from the censer amid the images of the faithful Hebrews and their guardian angel or indeed Christ himself, the object’s purifying function and its artistic form come together in an extraordinarily complex way. In a billowing cloud of incense, we see their deliverance in the present moment and anticipate Rénier’s as well. It is as if all the figures were sitting on coals while yet 'the fire did not touch them at all’ (Song of the Three Jews 27; Daniel 3:50 LXX).

References

Gearhart, Heidi C. 2013. ‘Work and Prayer in the Fiery Furnace: The Three Hebrews on the Censer of Reiner in Lille and a Case for Artistic Labor’, Studies in Iconography, 34: 103–32

Konstantinos Adrianoupolitis :

The Story of Daniel and the Three Youths in the Fiery Furnace, Second half of 18th century , Icon

Unknown artist :

The Three Hebrews in the Furnace, c.250–300 CE , Fresco

Unknown artist, France :

Censer depicting the Hebrews in the Fiery Furnace, c.1160–65 , Cast brass, chiselled and gilded

Faithful in the Flames

Comparative commentary by Peter S. Hawkins

As in the stories of Daniel in the lions’ den and Jonah in the belly of the ‘great fish’, the moral of this episode is simple: deliverance is at hand, for God spares those who keep the faith.

The narrative in Daniel 3 is, by contrast, elaborate. It gives us crowd scenes, a dialogic back and forth, ‘every kind of music’, a detailed description of clothing as well as of instrumentation, and a dramatic reversal of expectation. An artist approaching this story has much to go on.

That said, an artwork’s focus might be on narrative essentials alone, as in the wall painting in the third-century catacomb of Priscilla. There we see only the three young Hebrews in the flames, with a divine presence hovering just above them and offering protection. In the catacomb’s funerary context, the image goes to the heart of the matter: death does not have the last word. In the late-Byzantine icon, on the other hand, there is a welter, even a superfluity, of visual ‘information’. The icon writer takes an expansive view, a fuller account than the one given in Daniel 3. Rather than opening a window onto heaven, the icon illustrates and extends the text.

But what text are we working with? The Hebrew Bible, and the Protestant Scriptures that follow it, give the events of the story as seen from outside the flames, and in prose. By contrast, the Scriptures of the Orthodox (working from the Greek Septuagint) and Roman Catholics (drawing on the Latin Vulgate) take us inside the conflagration, and into poetry. Between Daniel 3:23 and 3:24 they offer a suite of verses with two psalms or odes that record the prayers of the young men in the flames. One, known as the ‘Prayer of Azariah’ (Abednego), is a penitential plea for deliverance (vv.24–45 LXX); the other, the in-unison ‘Song of the Three Jews’ (vv.51–90 LXX), blesses God, as in Psalm 148, for the manifold gifts of creation.

The Song is commonly identified by its opening word in the Latin, Benedicite. It became a fixture in liturgies both East and West, but is especially important in Orthodox churches, which not only commemorate the deliverance on a fixed feast day (17 December), but also use the Song both in evening offices throughout the year and in the liturgy of Holy Saturday. (There is also evidence of a late-medieval liturgical drama, a Service of the Furnace, observed in Hagia Sophia and elsewhere; Lingas 2010.)

All the works in this exhibition assume the expanded version of Daniel 3. For this reason, we can imagine that whenever the three Hebrews are shown in the prayer position they would have on their lips, ‘Blessed art thou, O Lord, God of our fathers, and to be praised and highly exalted for ever (Song of the Three Jews 29; Daniel 3:52 LXX). Some representations make this explicit by including the opening words of the Benedicite within the work, so that the text, regularly sung in church, comes easily to mind when venerating the picture or, in the case of the medieval censer, when using the object liturgically to sanctify. The upper border of the icon, for instance, reads:

In times past, the three children did not fall down and worship the golden image, the Persian idol, but chanted in the middle of the furnace: O God of our fathers, blessed are you.

The fourth ‘man’ in the iconography of Daniel 3 is identified both as ‘an angel of the Lord’ (Prayer of Azariah 26; Daniel 3:49 LXX) and ‘like the Son of God’ (Daniel 3:25 NRSV; v.92 LXX). He is pictured in various ways. In the catacombs, he is ‘like’ a dove and therefore more like the Holy Spirit than the Saviour. At the apex of the twelfth-century medieval censer, he is more obviously readable as an angel (even if missing his telltale wings)—although given his greater size, seated position, and facial expression, he also has more than a passing resemblance to Christ, who was often thought to be the fourth man in the furnace. In the icon we see a winged angel embracing the three Hebrews, whose halo bears a christological cross embedded faintly in gold—a reflection of the ‘Son of God’ he was often taken to be. In every case, the Daniel image suggests the joy of a divine rescue, as if each one, though silent, gives voice to the Benedicite refrain, ‘bless the Lord: praise and exalt him above all for ever’.

References

Lingas, Alexander. 2010. ‘Late Byzantine Cathedral Liturgy and the Service of the Furnace’, in Approaching the Holy Mountain: Art and Liturgy at St Catherine’s Monastery in the Sinai, ed. by S. Gerstal and R. Nelson (Turnholt: Bepols), pp. 179–230

Commentaries by Peter S. Hawkins