1 Maccabees 1:1–9

The Marvellous King the Bible Could not Ignore

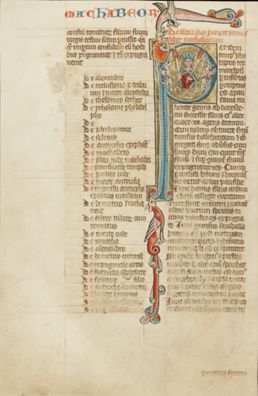

Unknown artist, Austria

Alexander’s Flight to the Heavens with Griffins, from Peter Comestor’s Historia Scholastica, c.1300, Manuscript illumination, The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles; MS Ludwig XIII.1, fol. 222v, Digital image courtesy of the Getty's Open Content Program

Not Even the Sky is the Limit

Commentary by Claudia Daniotti

Placed under the heading ‘De alexandro Incipit primus liber machabeorum’, this picture from a codex of Peter Comestor’s twelfth-century Historia Scholastica is unrelated to the text it illustrates, for the episode depicted is not recounted by Comestor or anywhere else in the Bible. It shows a crowned Alexander sitting in a casket drawn by two griffins, which—enticed by the meat placed on the two skewers held by Alexander above their heads—are lifting him up in the air.

In the Middle Ages, ‘the Flight to the Heavens with Griffins’ was by far the most famous of all the marvellous adventures told in the Alexander Romance, a text which, in its many versions, played a paramount role in the transmission of the myth of Alexander.

In the Romance, the ancient conqueror is transformed into a fabled hero and fearless explorer, who travels to the end of the world among monsters, dangers, and wonders beyond belief. For this Alexander, not even the earth was enough. Having explored the ocean in a purpose-built submarine vessel, he was taken by the desire to explore the heavens—a task he carried out in his griffin-powered flying machine, only to be sent back to the earth by a divine being (which some versions of the Romance identify with the Christian God).

The Getty Alexander is a remarkable example of the astounding popularity that the episode of the Flight enjoyed in medieval Europe, when it was represented in nearly every artistic medium, including tapestries, sculpted reliefs, floor mosaics, and misericords. As Chiara Frugoni once noted, for the illuminator of the Getty manuscript, given the task of providing a visual commentary on the scriptural passage in 1 Maccabees 1 concerning the Macedonian, the choice was obvious: ‘[it] is, must be, Alexander with the griffins, who was regarded as inseparable from his most famous and widespread adventure’ (Frugoni 1973: 227; own translation).

References

Frugoni, Chiara. 1973. Historia Alexandri elevati per griphos ad aerem: origine, iconografia e fortuna di un tema (Rome: Istituto storico italiano per il Medio Evo)

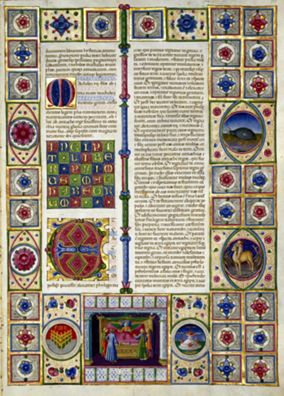

Taddeo Crivelli

Alexander Summoning His Generals to His Deathbed and Dividing His Empire Among Them, from the Bible of Borso d’Este (vol. 2), 1455–61, Manuscript illumination, Biblioteca Estense Universitaria, Modena; MS Lat. 423, fol. 110r, Courtesy Biblioteca Estense Universitaria

Dividing Lands and Spoils

Commentary by Claudia Daniotti

This lavishly decorated two-volume Bible comprises over six hundred richly illuminated sheets and is rightly considered the most precious book of the Italian Renaissance. Today in Modena, it was created between 1455 and 1461 for Borso d’Este, the Duke of Ferrara, by a team of artists led by Taddeo Crivelli and Franco dei Russi.

Placed in the lower register of folio 110r, in the second volume of the Bible, this illumination signals the opening page of the First Book of Maccabees and is an almost literal depiction of an event recorded in verses 5–6 of chapter 1: Alexander the Great summoning the Diadochi, his generals and successors, to his deathbed and dividing his empire among them. The last deed performed by the Macedonian conqueror in his short life is highlighted here on account of the fateful consequences it had. It resulted in the creation of the Seleucid Empire and eventually led to the dominion of Antiochus IV Epiphanes over Judaea. And from that ensued the events that are recounted in the First and Second Book of Maccabees: Antiochus’s persecution of the Jews and the Maccabean Revolt that followed it.

Although the accompanying text states that the Diadochi were the same age as Alexander (‘[they] had been brought up with him from youth’; 1 Maccabees 1:6), they are depicted here as young courtiers, while Alexander is portrayed as an aged, white-bearded king. This iconography is openly in contrast with the fact that Alexander died very young, but is well attested in the fifteenth century, when Alexander tended to assume the physical attributes of wisdom, most notably a beard.

In addition, his appearance in the Borso Bible may reflect the description of him as a sickly, weak man that is given in 1 Maccabees 5: having conquered and subdued most of the known world, Alexander ‘fell sick and perceived that he was dying’.

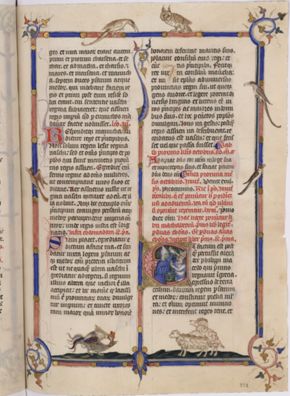

Unknown artist, Avignon

Alexander Killing Darius, from the Breviary of Pope Martin V, c.1360s–70s, Manuscript illumination, Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Vatican City; MS Vat. lat. 14701, fol. 251r, ©️ 2023 Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana

The Murder That Never Was

Commentary by Claudia Daniotti

Framed by the initial E illuminated on a manuscript page, a brutal assassination is happening before our eyes: two fully-armoured, helmeted warriors are facing each other, the man on the left plunging his sword into the face of the one on the right, who is wearing a crown that identifies him as a king.

The attacker on the left can surely be identified as Alexander the Great, and the warrior on the right as the King of Persia, Darius III, whose blood-covered face leaves us in no doubt as to his imminent death.

Yet the murder represented in this image, which marks the beginning of the First Book of Maccabees in the Breviary of Pope Martin V (r. 1417–31), never in fact happened. Rather, it is the result of an interesting misinterpretation of the text it illustrates. In the Latin version of the Vulgate, the text of Maccabees begins by saying that Alexander ‘percussit’, i.e. ‘defeated’, Darius (1 Maccabees 1:1). Between the fourth and the twelfth century, authors commenting or relying on this passage, such as Jerome (c. 347–419/420), Rabanus Maurus (c.780–856), and Honorius of Autun (c.1080–c.1140), misinterpreted the verb ‘percussit’ as ‘occidit’, giving rise to the idea that Alexander ‘killed’ Darius and transmitting to some later writers the notion of Alexander being directly responsible for Darius’s death.

Ancient sources do tell us that Darius was murdered; not, however, by his enemy Alexander, but rather by his own satrap and kinsman Bessus, who briefly usurped his throne before being executed on Alexander’s orders.

The erroneous idea that Alexander was Darius’s killer continued to have currency in medieval exegetical works and encyclopaedic compilations throughout the Middle Ages. Despite this, however, it is notable that in the visual tradition pictures of Alexander murdering Darius are rarely found. This makes the image in the Breviary of Pope Martin V (now in the Vatican Apostolic Library) all the more extraordinary, on account of both its beauty and rarity.

Unknown artist, Austria :

Alexander’s Flight to the Heavens with Griffins, from Peter Comestor’s Historia Scholastica, c.1300 , Manuscript illumination

Taddeo Crivelli :

Alexander Summoning His Generals to His Deathbed and Dividing His Empire Among Them, from the Bible of Borso d’Este (vol. 2), 1455–61 , Manuscript illumination

Unknown artist, Avignon :

Alexander Killing Darius, from the Breviary of Pope Martin V, c.1360s–70s , Manuscript illumination

Weaving Together Pagan and Sacred History

Comparative commentary by Claudia Daniotti

The First Book of Maccabees opens with a section devoted to the life of Alexander the Great (356–323 BCE). The son of Philip II of Macedon and Olympias, Princess of Epirus, Alexander became king at the age of twenty, set out on his journey to Asia at twenty-two, conquered the Persian Empire from Egypt to India in less than ten years, and died suddenly in Babylon in June 323 BCE, shortly before his thirty-third birthday. It is not surprising that the memory of such an exceptional life found its way into histories and cultures far and wide, so much so that Alexander is the only really towering figure of Graeco-Roman classical antiquity to be mentioned in the Bible (or at least, those versions of the Bible in which the deuterocanonical literature is included). Incorporated into the scriptural text despite being only tangentially related to its narrative—in a sense, this is a story he does not ‘belong’ to—he thus secures a permanent place in Jewish and Christian sacred history.

At the beginning of 1 Maccabees 1 (vv.1–7) an account of Alexander’s military career appears, from the destruction of the Persian Empire and the defeat of many kings, to his death and the partition of his kingdom among his generals, with a final mention (vv.8–9) of the reigns of the Diadochi (Ptolemy who ruled in Egypt, Seleucus in Asia, Lysimachus in Thrace and, after a long and bitter war, Cassander in Macedon). This summary of Alexander’s life is included as a prelude to the story of the disreputable Antiochus IV, the successor of Alexander’s general Seleucus and persecutor of the Jews, whose infamous deeds are told in the Books of Maccabees.

As predecessor of bloodthirsty Antiochus, Alexander is presented here as a ferocious man whose conquering, killing, and plundering was stopped only by a sudden death. Notably, the account in 1 Maccabees was the basis for the theological conception of Alexander throughout the Middle Ages—alongside two allegorical prophecies of Daniel (7:6 and 8:1–26) as interpreted by St Jerome, who saw in them an allusion to Alexander and his kingdom. The negative view of Alexander found in Maccabees and in Jerome’s Daniel is important, albeit not dominant, because it underpins the approach of many of the biblical commentaries, chronicles, and universal histories written in the Middle Ages, particularly in Germany.

From a visual point of view, the beginning of the First Book of Maccabees is a privileged place in illuminated manuscripts, where images of Alexander can be found. No survey of these occurrences exists, but the examples chosen and discussed here give a glimpse into that particular branch of visual depictions of Alexander that relates to biblical texts. Decorated initials marking the opening of 1 Maccabees usually present a generic portrait of Alexander, often with his horse Bucephalus, such as in the magnificent Bibbia bizantina (c. 1175–1200) of the Biblioteca Guarneriana (San Daniele del Friuli, north-east Italy). Albeit less frequently found than portraits, narrative scenes are more interesting for us, because they shed light on the impact that the text of Maccabees had on Alexander’s visualization in medieval traditions.

In the Bible of Borso d’Este, the fateful division of the empire (a subject almost unique in iconography) becomes an opportunity to turn the dying Alexander into a wise old king and his generals into the perfect courtiers of Renaissance Ferrara—the court for which this manuscript was commissioned and where Alexander was regarded as the ideal prince to look up to and emulate.

Occasionally, the interplay between written text and visual imagery gave rise to odd pictures that twist historical facts, such as Alexander killing Darius from Martin V’s Breviary. The (mistaken) notion of Darius’s death at the hands of Alexander is the result of a textual misinterpretation, which contradicts every account of Darius’s death we possess. This version of the episode remained a rare iconography in medieval Europe; but it is a remarkable example of the direct influence of Maccabees on Alexander’s visual tradition.

In contrast to this odd rendition of Darius’s murder, the Maccabees account in Peter Comestor’s manuscript gives pride of place to Alexander’s legendary adventure par excellence—his Flight to Heaven with Griffins. The story was marked by a profound ambiguity, which led it to be regarded either as an iconic, ideologically-charged image of power or as a symbol of Alexander’s overweening pride, not least in connection with Christ’s Ascension to Heaven, of which this seemed a blasphemous imitation.

The enigmatic 1 Maccabees 1:3 comes to mind: ‘When the earth became quiet before him, he was exalted, and his heart was lifted up’.

References

Cary, George. 1954. ‘Alexander the Great in Mediaeval Theology’, Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes, 17.1/2: 98–114

Manzari, Francesca, 1995. ‘Da Avignone a Roma: committenza e decorazione di alcuni codici liturgici’, in Liturgia in figura: codici liturgici rinascimentali della Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, ed. by Giovanni Morello and Silvia Maddalo (Rome: Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana and De Luca), pp. 59–65

Pfister, Friedrich. 1958. ‘Dareios von Alexander getötet’, Rheinisches Museum für Philologie, 101: 97–104

Commentaries by Claudia Daniotti