Matthew 13:53–58; Mark 6:1–6; Luke 4:14–30

Open to the Unexpected

James Tissot

The Brow of the Hill near Nazareth (L'escarpement de Nazareth), 1886–96, Watercolour over graphite on paper, 214 x 133 mm, Brooklyn Museum; Purchased by public subscription, 00.159.72, Brooklyn Museum of Art, New York, USA / Bridgeman Images

The Brow of the Hill

Commentary by David Brown

In contrast to Matthew’s account of Jesus’s rejection at Nazareth, Luke’s divergences from Mark’s account are substantial.

One is a quite different narrative placement for the incident. Mark locates it in the middle of Jesus’s ministry, whereas Luke uses it to set the scene for the ministry as a whole, with Jesus using words drawn from Isaiah (Luke 4:18–19) to inaugurate his new role. Also, compared with Matthew and Mark, Luke’s account keeps family references to a mere ‘Is not this Joseph’s son? (Luke 4:22; contrast Mark 6:3, Matthew 13:55–56). In their place comes a lengthy comparison with earlier treatments of the prophet Elijah (Luke 4:24–7). Finally, a dramatic conclusion is added (vv.29–30), in which the people attempt to kill Jesus by throwing him over a nearby hill.

James Tissot (1836–1902)—a French society painter who lived in London between 1871 and 1882—seems to refer to this last incident in this painting. Tissot experienced a dramatic visionary conversion in the Paris church of Saint-Sulplice in 1885 and painted over 350 small watercolours of the life of Christ over the course of the following decade. He exhibited these to great acclaim in Paris, London, and New York, and they were acquired just before the turn of the century by the newly opened Brooklyn Museum in New York. Two of these watercolours were devoted to Luke’s version of Jesus’s visit to the Nazareth synagogue. One shows Jesus’s unrolling of the scroll from which he will then read. This other one shows what ensues: his near lynching.

In The Brow of the Hill Tissot engages with Luke’s decision to conclude the story in this way. We may mistake the calmly meditative figure in the centre of the scene for Jesus, whom Tissot always dressed in white—but he is not. Rather, he is used as a foil to the crowd, who gesticulate madly at the mysterious escape of Jesus from their midst: in itself, its own kind of miracle.

References

Dolkart, Judith F. (ed.). 2009. James Tissot: The Life of Christ (New York: Merrell)

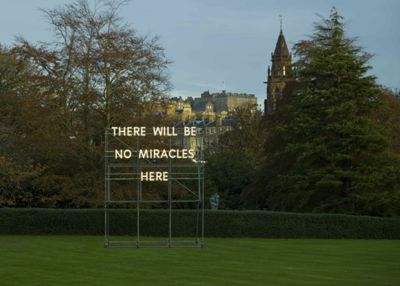

Nathan Coley

There will be no Miracles Here, 2007–09, Electric lights, scaffolding, Dimensions variable, Scottish National Gallery Of Modern Art [Modern Two]; Purchased with assistance from the Art Fund and the Patrons of the National Galleries of Scotland 2011, GMA 5138, ©studioNathanColey Antonia Reeve

There Will Be No Miracles Here

Commentary by David Brown

One issue that perplexed the early church was why, if Jesus really was the fulfilment of the Hebrew scriptures (as they believed), his own people rejected him. This episode offers one explanation: those closest to something are often unable to perceive its significance. Indeed, in Mark 6:4 we find a popular proverb being quoted to that effect: ‘[a] prophet is not without honour, except in his own country’. Meanwhile the previous verse indicates that it is precisely because the people know Jesus’s family well that they doubt that he could have any larger importance. The result is that in Nazareth Jesus ‘could do no mighty work’ (v.5).

Nathan Coley’s (b. 1967) installation There will be no Miracles Here (2007–9) now stands prominently in the grounds of the Scottish Gallery of Modern Art (Modern Two) in Edinburgh. Its inspiration came from a situation at the opposite extreme to that envisaged in Mark: too many miracles. This radiant announcement echoes and subverts a seventeenth-century royal proclamation aimed at curtailing the stream of pilgrims to the French village of Modseine which had laid claim to frequent miracles. These claims were to stop, by order of the King.

Yet at another level the Gospel proclamation and this royal announcement address situations not all that different. Both are managing expectations. If the authorities in France feared losing control of a situation of heightened religious excitement, the Gospel feels the need to offer an explanation of an anomalous situation that is its concern: why was Jesus rejected in his home town? Why was there no ‘mighty work’?

In an earlier work, the Lamp of Sacrifice (2004), Coley recreated 286 places of worship in Edinburgh in cardboard. The artist’s title alludes to John Ruskin’s positive view of Christianity laid out in The Seven Lamps of Architecture (published 1849). However, the presentation of churches in this way probably raised questions for a general viewer. What was the value of what was being presented?

Similarly, in the absence of any background knowledge, viewers are interrogated about the status of the statement ‘There are no miracles here’. They must decide for themselves what the meaning and legitimacy of such a declaration might be.

References

Morrison, Ewan. 2017. Nathan Coley (Edinburgh: National Galleries of Scotland)

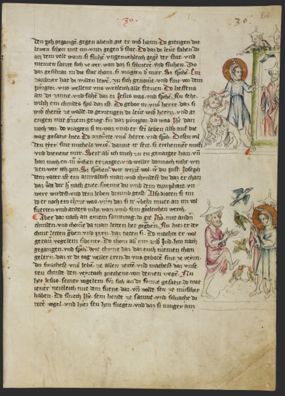

Unknown German artist

Jesus Raises the Clay Birds of his Playmates to Life, from Klosterneuburger Evangelienwerk, c.1340, Illumination on parchment, 380 x 275 mm, Schaffhausen, Stadtbibliothek, Switzerland; Gen. 8, fol. 28r, https://www.e-codices.ch/en/list/one/sbs/0008

Jesus Raises the Clay Birds

Commentary by David Brown

The Gospel of Matthew’s account of Jesus’s rejection at Nazareth largely follows the Gospel of Mark’s. But in Matthew 13:58, Mark 6:5’s ‘he could do no (ouk edynato) mighty work there’ becomes ‘he did not do (ouk epoiēsen) many mighty works there’. This departure from Mark’s version is often interpreted as ‘correcting’ Mark’s suggestion of a lack of power in Jesus. In fact, Mark 6:5 actually does mention some healings, so Mark may intend to imply (as some early interpreters like Origen Commentary on Matthew 10.19 thought) that miracles require two elements: divine power and a faithful response to recognize them.

It is often assumed that the apocryphal gospels of Jesus’s infancy took a quite different line, in making him a constant and effective miracle worker from the very beginning. Among the best known of these miracles is the transformation of sparrows the young Jesus had made from clay into real birds (recounted in the Infancy Gospel of Thomas). Indeed, so popular was the story that it not only appears twice in the Qur’an (3.49; 5.110) but also acquired semi-canonical status within Christianity, as can be seen from its appearance in the anonymous fourteenth-century vernacular harmonized gospel text from which this illustration is drawn.

More recent scholarship has disputed an obsessive preoccupation with miracles as the explanation of why these scenes of infant wonder-working appealed to so many. For one thing, such miracles were presented as generating just as much hostility as the adult encounter in Mark 6 and parallels—an episode without accompanying miracles. The reprimanding adult in this manuscript illustration is evidence of that. So perhaps their real motivation can be seen to lie in allowing Jesus to identify with common human concerns, as in this instance with a children’s game of the time.

In some ways, then, these miracles ask to be read alongside the Gospels’ references to Jesus’s expression of human emotions such as compassion and anger or his eating and drinking with ordinary folk—one more way of endorsing John’s declaration that ‘the Word became flesh and dwelt among us’ (1:14).

References

Davis, Stephen J. 2014. Christ Child: Cultural Memories of a Young Jesus (New Haven: Yale University Press)

Origen. Commentary on Matthew. 1896. The Ante-Nicene Fathers: Vol. 9—Recently Discovered Additions to Early Christian Literature, ed. by Allan Menzies (Buffalo: Christian Literature), p. 426

James Tissot :

The Brow of the Hill near Nazareth (L'escarpement de Nazareth), 1886–96 , Watercolour over graphite on paper

Nathan Coley :

There will be no Miracles Here, 2007–09 , Electric lights, scaffolding

Unknown German artist :

Jesus Raises the Clay Birds of his Playmates to Life, from Klosterneuburger Evangelienwerk, c.1340 , Illumination on parchment

A Prophet in His Own Country

Comparative commentary by David Brown

‘Can anything good come out of Nazareth?’ (John 1:46). If one of Jesus’s future disciples, Nathanael, had such a low opinion of Jesus’s home town, we may ask whether its inhabitants thought any better of it. Could anything wonderful emerge from the place? If so, what would it possibly look like?

While the word Mark uses for miracle in this passage is simply the common Greek word for ‘power’ (dynamis), our own word ‘miracle’ in its original Latin sense (miraculum) conjures up better the issue that Mark wishes to confront in his account of this incident: that recognizing significance is partly dependent on prior attitude, a readiness to respond to individuals and events at the very least with surprise, or in more spectacular cases with awe and wonder (the root meaning of the Latin word).

Nathan Coley’s light-and-text installation was first placed on the outskirts of the city of Stirling in central Scotland. Whether its citizens read the notice as no more than an endorsement of the unsurprising reality in which they lived or felt summoned to challenge Coley’s ambiguous message, I do not know. For some, perhaps, the work had the air of some kind of sad leftover from a carnival or fairground. An empty structure that might once have supported or witnessed something marvellous but was now abandoned.

Thanks to its subsequent central placement on the approach to a modern art gallery, visitors now find themselves encouraged to question the nature of modern and contemporary art in light of its statement. Such art often makes its mark through provocation and the unexpected. By this measure, Jesus’s whole life as recounted in the Gospels can also be likened to a work of art; he too provokes and surprises, challenging his audiences to discover more than what they believe they already know. But, whether it is the modern art gallery or Jesus that we face, our own expectations come under scrutiny too. Are we expecting too much or too little—from either?

In the Infancy Gospel of Thomas from which the story of the clay birds is derived, Joseph is represented as repeatedly attempting to deter Jesus from his miraculous deeds—unlike in other apocryphal infancy gospels (such as Pseudo-Matthew) which have Jesus’s parents in perpetual awe at the child’s behaviour. In this episode, he is joined by a Jewish neighbour in objecting to Jesus’s making clay birds on the sabbath. The illustration diverges from its text in not foregrounding Joseph: the conical Jewish hat and absence of halo suggest that the figure objecting to Jesus’s actions is a generically representative ‘Jew’. But whether in the form of parents or other adults, authority figures are shown (by text and image) not always to be right. In an expansion of those described by the Gospels as opposing Jesus to include neighbours and even family, there is an open invitation to us to think again about our assumptions.

James Tissot was fond of representing the miraculous (over thirty examples are to be found in the collection of watercolours in Brooklyn), so it is perhaps not altogether surprising that he makes the events of Jesus’s return to Nazareth something of a miracle too, with ‘the brow of the hill’ transformed into a vast gorge. While the Lukan narrative may foreground the wrath of the people of Nazareth, Tissot focuses instead on their puzzlement: how could Jesus have successfully escaped their clutches? Wonder at the mystery of the man has thus become of central importance in this composition.

Some of his friends doubted the sincerity of Tissot’s conversion. But if genuine, as seems plausible, we may see in it an openness that successfully reverses the pattern set by Mark. For the Evangelist those surrounding us in formative years can inhibit new perceptions. Tissot—despite his somewhat wild adult life—seems to have remained at least open to the ideas he had learned in his youth (his mother had been a devout Roman Catholic). Parents may not always be right, but maybe sometimes they are.

All three artworks may therefore challenge us to read the text, not principally as a condemnation of the narrowness of the people of Jesus’s home town, but rather as an encouragement—addressed also to us—to be open to the unexpected, to be ready to revise our expectations, and to find the wondrous still at work and, maybe, near at hand.

A similar challenge may face today’s Church. New interpretations of where revelation is pointing it continue to emerge, even when, like the people of Jesus’s Nazareth, the Christian community is tempted to think it has all the answers.

References

Elliott, J. K. (ed.). 1996. The Apocryphal Jesus: Legends of the Early Church (Oxford: Oxford University Press), pp.19–30

Commentaries by David Brown