Numbers 35; Deuteronomy 4:41–43; Joshua 20

Cities of Refuge

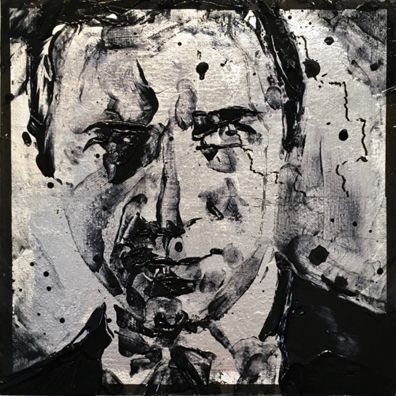

Carlo Gianferro

Gjion Biamishtea, 2014, Photograph; © Carlo Gianferro

Blood Feud

Commentary by Caleb Froehlich

The appointment of the cities of refuge in Numbers 35, Joshua 20, and Deuteronomy 4:41–43 was to provide the accidental killer a relief from living in the shadow of a blood avenger’s looming threat. Although it may be difficult for us to fully grasp the significance of this relief for an accidental killer living in ancient Israel, we may gain some insight by glimpsing an accidental killer’s fate within a contemporary context where such relief is distant and often unattainable.

This photograph by Italian photographer Carlo Gianferro is one of seven portraits made for an online article entitled ‘Albania: The Dark Shadow of Tradition and Blood Feuds’. Each portrait documents the conditions of the life of Albanians who have been forced into their own personal prisons by an ancient code of retaliation. Gjion Biamishtea, man portrayed here, accidentally killed a girl and now confines himself to a house in Vraka, near Shkodër, fearing that the girl’s family will find him and avenge her death with a retaliation killing (Mattei 2016).

The moment Gianferro’s photograph captures is one of dispirited melancholy. Biamishtea exhales smoke from his cigarette, shrouding all his facial features save the emptiness in his eyes. These wisps underscore his lifeless existence. No longer having a place in society, it is as if his very identity as a person is fading away. He almost recedes into his dilapidated environs.

If the lives of accidental killers in ancient Israel were at all comparable to the conditions that Biamishtea and other Albanians like him endure on a daily basis, then the relief afforded by the cities of refuge was more than simply escaping the feud. It was an opportunity to begin life anew, to restore a sense of personhood in society unfettered by the previous tragedy.

References

Mattei, Vincenzo. 2016. ‘Albania: The Dark Shadow of Tradition and Blood Feuds, 14 May 2016’, www.aljazeera.com, [accessed 11 February 2020]

Ai Weiwei

Arch, from the series 'Good Fences Make Good Neighbors', 2017, Galvanized mild steel and mirror polished stainless steel, Washington Square Arch, Washington Square Park, Manhattan; © Ai Weiwei. Photo: Ed Rooney / Alamy Stock Photo

Complex Hospitality

Commentary by Caleb Froehlich

Arch was the signature work of Ai Weiwei’s ‘Good Fences Make Good Neighbors’ (on view 2017–18), a multisite exhibition concerned with the global refugee crisis, consisting of over 300 installations throughout New York City. Occupying the centre of the Washington Square Arch in Manhattan, this thirty-seven-foot-tall steel cage contained a reflective passageway in the form of two silhouetted human figures united in an embrace (Baume 2019: 19, 27, 32–33). In combining the form of embracing figures (suggesting openness and welcome) with that of a fence or cage (suggesting prohibition and exclusion), Ai powerfully conveyed the paradox of national borders.

This paradox is further expressed by the relationship between Arch and the monument it ‘occupies’. Drawing upon the long history of the Triumphal Roman arch, the Washington Square Arch is intended to celebrate the military might and victories of the United States Empire and its military hero/‘Emperor’ George Washington. The placement of Ai’s sculpture within this triumphant symbol of national territories and strength raises the question of how strong borders may or may not be compatible with welcoming borders, mirroring the tensions played out at the gates of the cities of refuge.

According to Numbers 35, Joshua 20, and Deuteronomy 4:41–43, when the accused killer arrived at the city gate, he was to present himself before the elders of the city who would conduct a trial to determine the context of the killing. If the court found that he had killed his victim intentionally, he would be handed over to ‘the avenger of blood’ who had the right to execute him; if the court found that he had killed his victim unintentionally, he would be admitted into the city of refuge and live there until the death of the then officiating high priest.

The immersive symbolism of Arch embodies the complexity of the hospitality inherent within the sanctuary practices of the cities of refuge. Although these cities offered welcome and protection to anyone who had killed someone, including the ‘stranger’ and the ‘sojourner’ (Numbers 35:15), such welcome and protection was highly dependent upon a requisite process intended or designed to ascertain the killer’s motive (Bagelman 2016: 78–79). Arch, of course, does not cross-examine its visitors in this manner, but its imagery draws out the inherent tensions of the gateway, evoking the same contradictions which characterize the sanctuary practices detailed in these biblical passages.

References

Bagelman, Jennifer J. 2016. Sanctuary City: A Suspended State (New York: Palgrave Macmillan)

Baume, Nicholas. 2019. Ai Weiwei: Good Fences Make Good Neighbours (New Haven: Yale University Press)

Monica Lundy

Bela Lugosi, 2017, Mixed media on panel overlaid with silver leaf, 5.25 x 5.25 cm, Collection of the artist; © Monica Lundy; Photo: Courtesy of the artist and Nancy Toomey Fine

Rising Stars

Commentary by Caleb Froehlich

The provisions for a refugee who found sanctuary in a biblical city of refuge are summed up in the simple words ‘and live’ (Deuteronomy 4:42). In Talmudic tradition, this meant more than simply being protected from blood vengeance. It meant that refugees were entitled to all the amenities that would allow them to live as a productive member of the community, including opportunities for education and employment, even the eligibility to receive honours (Babylonian Talmud Makkot 10a).

These provisions are illuminated by Monica Lundy’s portrait Béla Lugosi (2017). Included as part of the 2017 exhibition series ‘Sanctuary City: With Liberty and Justice for Some’, a yearlong tribute to American immigrants which took place in Los Angeles, San Francisco, and Berkeley, California, this portrait celebrates the Hungarian actor Béla Ferenc Dezső Blaskó. Béla fled his homeland during the Hungarian Revolution of 1919 migrating to the United States, where, taking the name ‘Lugosi’ in honour of his birthplace, he became an iconic figure in American horror films. He is best known for his role as Count Dracula in Tod Browning’s classic 1931 film (Rhodes 1997: 3–38).

Lundy chose to paint Béla’s face on silver-leaf to play with the notion of the ‘silver screen’, a phrase synonymous with the era of Hollywood in which Béla reached the height of his career. Her use of messy drips and finger smudges to define his brow nose, and cheeks over this opulent backdrop conveys both a distress and dignity, representing Béla’s struggle as an immigrant and his success in the film industry.*

We might imagine a similar portrait being created to honour a refugee who lived in one of the biblical cities of refuge. According to Talmudic readings, the provisions and supports available in the city would allow a refugee to rise high—even, perhaps, achieving heights like those scaled by the modern-day celebrities commemorated in the ‘Sanctuary City’ exhibition.

References

*I want to thank Monica Lundy for taking the time to discuss her painting with me via email

Pleasant, Amy. 2017. ‘Artist’s Mobilize: With Liberty and Justice for Some … An Exhibition Honoring Immigrants, 19 January 2017’, www.huffpost.com, [accessed 11 February 2020]

Rhodes, Gary Don. 1997. Lugosi: His Life in Films, on Stage, and in the Hearts of Horror Lovers (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company)

Carlo Gianferro :

Gjion Biamishtea, 2014 , Photograph

Ai Weiwei :

Arch, from the series 'Good Fences Make Good Neighbors', 2017 , Galvanized mild steel and mirror polished stainless steel

Monica Lundy :

Bela Lugosi, 2017 , Mixed media on panel overlaid with silver leaf

Face-to-Face

Comparative commentary by Caleb Froehlich

Numbers 35, Joshua 20, and Deuteronomy 4:41–43 record the appointment of six Levitical cities as ‘cities of refuge’ to ensure that if there was an accidental killing, the accused killer could flee to one of these cities and be protected from the menace of the ‘avenger of blood’, living there until the death of the high priest, after which he was free to return to a normal lifestyle.

These provisions were a significant improvement on the prior tradition of blood vengeance, or the duty of the closest relative of a murdered victim to avenge the murder. Where this tradition maintained that the relative had the right to slay the accused with impunity, regardless of whether the accused was actually culpable of murder, the cities of refuge brought to light the extenuating circumstances of the accused so that he might be considered innocent of murder.

In a setting where the accused was essentially rendered ‘faceless’, his identity defined entirely by one tragic occurrence, the cities were opportunities for justice. They were places of hospitality and rehabilitation, looking beyond the stigma. They were places for face-to-face encounter.

All three artworks under consideration here play with the notion of face-to-face encounter. While each uses the encounter to highlight different aspects of the refugee experience in today’s socio-political climate, they also serve as a fitting analogy for considering the provisions of the biblical cities of refuge from the perspective of sanctuary-seekers.

Carlo Gianferro’s photograph, for example, conveys the self-imposed anonymity of a sanctuary-seeker living outside the protection of the cities of refuge. It captures a moment in the life of Gjion Biamishtea, an accidental killer who now lives in isolation for fear of retribution from the victim’s family, not unlike blood vengeance in ancient Israel. However, this portrait frustrates our attempts to empathize with Biamishtea and his circumstances. Most of the identifying features of his face are quite literally obscured by wisps of smoke. Whatever shame, anxiety, guilt, or fear he may be feeling can only be hinted at through his eyes which, ironically, look down and away. We are confronted with a nearly faceless ‘killer’.

By contrast, Monica Lundy’s painting Béla Lugosi places its subject’s face in full view. Here we see a representation of the possible heights a sanctuary-seeker may achieve with the supports available to him in one of the cities of refuge. The portrait commemorates the life and accomplishments of Béla Ferenc Dezső Blaskó, an American immigrant who became a Hollywood icon. Its monumentality, conveyed both through its silver backdrop and its extreme close-up of Béla’s confident expression, belies its smudgy quality and small scale. We could interpret this portrait as signifying the difficulties and seeming insignificance Béla endured as an immigrant in the United States, but it is also an evocative expression of his accomplished stardom as a result of the efforts he and others expended to enable him to prosper in his new setting.

Ai Weiwei’s immersive sculpture Arch differs from Gianferro’s and Lundy’s portraits in that it did not have a face as part of its structural composition. Instead, visitors encountered their own faces reflected in the embrace of two human silhouettes as they passed through the sculpture’s opening.

Through this face-to-face encounter, Arch placed its visitors under a scrutiny which resembles the requisite process sanctuary-seekers went through to be admitted into the cities of refuge. The sculpture may not have conducted a trial to determine whether visitors were innocent of murder, but it did provoke a reflective examination which might have awakened those passing through its middle to consider the question of belonging—who belongs here and to whom does this city belong? The same question lay behind the deliberations at the gates of the cities of refuge.

In both the trial at the city gates and the reflective examination at the sculpture, however, the willingness to accept the other was emphasized. Residents in the cities of refuge, most of whom were not accused killers, were charged to welcome the ‘stranger and the sojourner’ into their communities (Numbers 35:15). Much in the same way, Arch held welcoming the stranger at its centre. The faces visitors encountered in the mirror of the sculpture’s embracing figures prompted them to see sanctuary-seekers not as faceless ‘illegals’ amassed at fences and gates, but as persons like themselves, with loved ones, fears, hopes, dreams, and aspirations, entitled to all the amenities that would allow them to flourish as members of their own communities.

References

Bagelman, Jennifer J. 2016. Sanctuary City: A Suspended State (New York: Palgrave Macmillan)

Commentaries by Caleb Froehlich