Judges 3

Ehud and Eglon

Works of art by Brothers Dalziel, Ford Madox Brown, Unknown French artist [Paris] and Unknown Artist

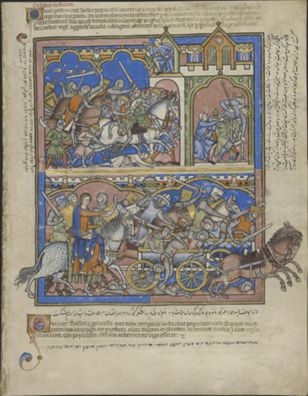

Unknown French Artist [Paris]

Ehud, a Clever Leader; Deborah, a Prophetess: Old Testament miniatures with Latin, Persian, and Judeo-Persian inscriptions from the Crusader Bible (The Morgan Picture Bible), c. 1244–54, Illumination on vellum, 390 x 300 mm, The Morgan Library & Museum, New York; Purchased by J.P. Morgan (1867–1943) in 1916, MS M.638, fol. 12r, Photo: The Morgan Library & Museum, New York

Having the Guts

Commentary by Brandon Hurlbert

The Morgan Bible, better known as the Crusader Bible, is an illuminated manuscript including over 300 scenes from the books of Genesis, Exodus, Joshua, Judges, Ruth, and 1–2 Samuel on 46 folios. Produced in Paris during the reign of King Louis IX (1214–70), many elements (buildings, battle scenes, and clothing) reflect its medieval and crusader context.

Three sets of inscriptions in Latin, Persian, and Judeo-Persian, surround each page and relate the illuminations to the biblical story. These inscriptions were added later. Their languages reflect the multiple previous owners of the Crusader Bible. From Paris, it eventually came into the possession of Cardinal Bernard Maciejowski (1548–1608) in Kraków, Poland, who then made a gift of the book to Shah ‘Abbas of Safavid Persia (1571–1629). After the sack of Isfahan (1722), it fell into the hands of an unnamed Persian Jew whose inscriptions sometimes correct the Latin, revealing a familiarity with the Hebrew Bible and/or Jewish tradition. For instance, the Latin inscription follows the Vulgate and makes clear that Ehud is ambidextrous. The Judeo-Persian inscription, however, follows the Hebrew Bible and makes no mention of this.

Folio 12r is the first scene from the book of Judges. It begins with Ehud’s assassination of Eglon, king of Moab (Judges 3:12–30), and Deborah’s story (Judges 4), which continues onto the next page.

Starting in the top register at bottom right, Ehud holds in his left hand an object, likely a reliquary or a pyx (an object holding consecrated eucharistic bread). These probably symbolize Ehud’s secret divine word to Eglon (Judges 3:19–20); in Christian terms, he holds the ‘Word’ which is Christ. Ehud uses his right hand to stab Eglon, whose intestines spill outward in gruesome detail.

Ehud is pictured again at centre emerging from an upper storey window to summon his troops to battle with a horn in one hand while holding the bloodied dagger with which he stabbed Eglon in his other.

The larger scene on the left shows Israel defeating the Moabites, which the Persian inscription mistakes as a rescue mission for Ehud. Ehud fled Eglon’s palace after the assassination and returned with an army to defeat the Moabite occupiers (vv.28–30). The fleeing Moabite soldiers are depicted in similar ways to their king, stabbed with their intestines exposed. The illumination enthusiastically captures the violence and gore that makes the biblical story so memorable.

References

n.d. ‘Inscriptions, The Crusader Bible’, available at https://www.themorgan.org/collection/crusader-bible/inscriptions [accessed 21 November 2023]

Leson, Richard et al. 2019. ‘MS M.638, Fol. 12r’, available at https://www.themorgan.org/collection/crusader-bible/23 [accessed 21 November 2023]

Weiss, Daniel Howard, and William Noel. 2002. The Book of Kings: Art, War and the Morgan Library’s Medieval Picture Bible (Lingfield: Third Millenium club)

Brothers Dalziel, after Ford Maddox Brown

The Death of Eglon, from 'Dalziels' Bible Gallery', 1865–81, Wood engraving on India paper, 151 x 186 mm (image), The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; Anonymous Gift, 1926, 26.99.1(51), www.metmuseum.org

Grasping the Point

Commentary by Brandon Hurlbert

The Dalziels’ Bible Gallery was published in 1881 and featured 62 wood engravings depicting various scenes from the Old Testament. Beginning the project in 1862, the Dalziel brothers commissioned over a dozen established artists to produce original artwork for their illustrated Bible. The book received glowing reviews but ultimately was a financial failure due to its high price, large size, and the lack of accompanying text.

Ford Madox Brown (1821–93) was responsible for this engraving along with two others in the project (‘Joseph’s coat’ and ‘Elijah and the Widow’s Son’). Each showcases his pre-Raphaelite style in its attention to detail and its desire to depict the subject matter with a degree of historical realism rather than in the adoption of classical or stereotypical poses. Brown drew inspiration from newly discovered archaeological findings from Assyria and Egypt displayed in the British Museum. Yet, as Donato Esposito has shown, Brown based many of the elements in this design (Eglon’s jewellery, the throne, floral patterns) on illustrations in Layard’s Nineveh and Its Remains (Esposito 2006: 280).

Brown has chosen to depict the moments before Eglon’s death. Ehud points upward, suggestive of his secret word from God (Judges 3:19). Eglon’s hands clutch the sides of his throne as he prepares to stand. Ehud’s left hand grasps the handle of the knife hidden beneath his clothes, leaving the viewer in a state of tension. Several details add verisimilitude, but most are only of the ‘Orientalist’ imagination—a naive and often paternalistic view of non-Western cultures as ‘exotic’ and unchanged across time and place. So, Ehud’s sandals are left at the door in accordance with ‘Eastern customs’. The inscriptions on the wall and dais resemble cuneiform but are nonsense. The flowing robes are suggestive of Bedouin dress.

Other details suggest biblical and theological reflection by the artist. The key Ehud will use to secure his escape hangs on a hook in the far left (Judges 3:23). The serpent armband and the serpent entwined sceptre, apparently dropped by Eglon, represent the Moabite king as Israel’s physical and spiritual enemy.

References

Esposito, Donato. 2006. ‘Dalziels’ Bible Gallery (1881): Assyria and the Biblical Illustration in Nineteenth-Century Britain’, in Orientalism, Assyriology and the Bible, ed. by Steven W. Holloway (Sheffield: Sheffield Phoenix Press), pp. 267–96

MacCulloch, Laura. 2012. ‘“Fleshing Out” Time: Ford Madox Brown and Dalziels’ Bible Gallery’, in Reading Victorian Illustration, 1855–1875: Spoils of the Lumber Room, ed. by Paul Goldman and Simon Cooke (Farnham: Ashgate), pp. 115–35

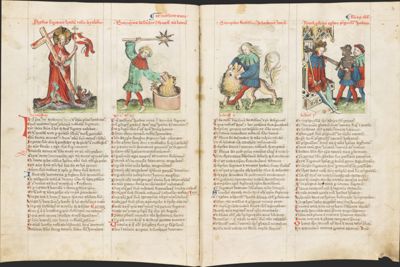

Unknown Artist

Samson tears the lion apart; Ehud kills King Eglon; Christ defeats the devil; Banaias kills a lion, from Speculum Humanae Salvationis, 1427, Manuscript illumination, Benedictine College, Sarnen, Switzerland; now in Benediktinerinnenkloster, Hermetschwil; Cod. membr. 8, fols 29v &30r, ©️ Bretscher-Gisiger Charlotte / Gamper Rudolf, Katalog der mittelalterlichen Handschriften der Klöster Muri und Hermetschwil, Dietikon-Zürich 2005, S. 158-161, Courtesy Benediktinerkollegium, Sarnen

Getting it in the Neck

Commentary by Brandon Hurlbert

The Speculum Humanae Salvationis (‘The Mirror of Human Salvation’) is a late medieval work that was widely reproduced in Europe during the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. Written anonymously sometime between 1309 and 1324, copies of the text generally feature 42 lessons in which a scene from the New Testament (usually from the life of Christ) is figurally linked with three episodes from the Old Testament, Apocrypha, or historical legends. These are accompanied by an explanation of the typological significance between them, usually in Latin, which could be used to instruct monks and priests. The pictures accompanying these texts, however, were designed to be sufficient on their own for the instruction of the less educated and often illiterate laity.

In the earliest copies, these pictures took the form of illuminated miniatures which were hand drawn with pen and appear to be standardized along with the text. Later fifteenth-century editions utilized woodcuts and moveable type which led to an even greater degree of standardization.

This manuscript was produced in 1427 and is likely of Swiss origin. Its illuminations are hand drawn with pen, and deviate noticeably from the biblical story and other versions of Speculum (e.g., in the inclusion of a mysterious third figure who is either helping Ehud or trying to prevent the assassination).

The illumination we see here at top right is the last in a series that signifies Christ’s defeat of Satan. The intervening two pictures in the sequence are of Beneniah, defeating a lion in a pit (2 Samuel 23:20) and Samson killing a lion (Judges 14:5–6). The Latin text accompanying the final illumination highlights the fatness of Eglon and his large belly, which symbolize the Devil’s hunger as he had ‘swallowed up all mankind’. Ehud’s victory prefigures Christ’s salvation and the Christian’s struggle with sin.

The picture, however, tells a different story from the text that accompanies it. Here, Eglon, seated on a throne, appears average size. Ehud is garbed in armour and uses both hands to grasp a broadsword. The depiction is an outlier among the other manuscripts which usually feature Ehud holding up Eglon’s hand while stabbing him in the belly. Here, Eglon is stabbed through the neck as blood pours out, thus mirroring the first picture in the series (at top left).

References

Köpf, Ulrich. 2011. ‘Speculum Humanae Salvationis’, in Religion Past and Present, online version, available at http://referenceworks.brillonline.com/entries/religion-past-and-present/speculum-humanae-salvationis-SIM_025659# [accessed 21 November 2023]

Nielsen, Melinda, (ed.). 2022. An Illustrated Speculum Humanae Salvationis: Green Collection MS 000321 (Leiden: Brill)

Wilson, Adrian, and Joyce Lancaster Wilson. 1984. A Medieval Mirror: Speculum Humanae Salvationis, 1324–1500 (Berkeley: University of California Press)

Unknown French Artist [Paris] :

Ehud, a Clever Leader; Deborah, a Prophetess: Old Testament miniatures with Latin, Persian, and Judeo-Persian inscriptions from the Crusader Bible (The Morgan Picture Bible), c. 1244–54 , Illumination on vellum

Brothers Dalziel, after Ford Maddox Brown :

The Death of Eglon, from 'Dalziels' Bible Gallery', 1865–81 , Wood engraving on India paper

Unknown Artist :

Samson tears the lion apart; Ehud kills King Eglon; Christ defeats the devil; Banaias kills a lion, from Speculum Humanae Salvationis, 1427 , Manuscript illumination

An Ambiguous Assassin

Comparative commentary by Brandon Hurlbert

Rounding off the prologue of the book of Judges (Judges 1:1–3:6), the opening verses of Judges 3 introduce the foreign nations remaining in the land who will test Israel and their devotion to YHWH.

The stereotypical Judges cycle detailed in Judges 2:11–23 begins with Othniel’s narrative. Israel first turns to idolatry, and then is oppressed by a foreign king. They cry out to the Lord, who raises up a judge (Othniel) to deliver them. The story concludes with the death of the Judge and a notice that the land was quiet.

The third judge, Shamgar (Judges 3:31) represents a different style of narration—probably due to the book’s complex compositional history.

Between these two short accounts lies the narrative of Ehud and Eglon. Following Othniel’s death Israel had again turned to foreign gods. YHWH first raises up Eglon, the king of Moab, who oppresses Israel for eighteen years, before also raising up Ehud as Israel’s deliverer. The story appears quite simple: Ehud gains an audience with the king with a promise of a divine word. After assassinating Eglon with his concealed dagger, Ehud locks the door and flees while the servants wait for their king to finish his business. Ehud rallies the troops and seizes the river crossing against the Moabite army.

In recent interpretations, two elements of the narrative have been understood as extremely significant: Ehud’s left-handedness and Eglon’s body. Ehud is characterised as a Benjaminite and a ‘man bound in his right hand’ (Hebrew: ish itter yad-yemino). This description could mean several things: it could be an idiom for left-handedness; it could imply a social and/or physical disability; or it could indicate Ehud is of an elite warrior class (warriors would often bind their dominant hand to improve their combat ability with their offhand). A left-handed ‘Benjaminite’ (which means ‘son of the right’) may additionally point to Ehud’s ironic and underhanded characterization. The ambiguity of this word is represented in the various ancient translations. The Targum (Aramaic) and the Syriac versions suggest that Ehud is disabled, while the Greek versions read ‘ambidextrous’ (amphoterodexion), an interpretation which is followed by the Old Latin and Vulgate. This may explain why both the Crusader Bible and Speculum have chosen to depict Ehud as using both hands, as they would have relied on the Vulgate.

Eglon’s body is described as ‘very fat’ (Hebrew: bari meod), which has been understood by many modern readers to indicate obesity. The description in its narrative context is thus often understood to be comically obscene and grotesque. Even though the phrase may actually mean a king who is ‘well-built’, it is not surprising that a satirical reading which mocks Moab vis-à-vis its corpulent king has become dominant.

Along with its humorous depiction of the servants, the text appears to relish its depiction of the violence and gore of the episode, with imaginative descriptions of fat closing over the blade and sh*t covering the floor (modestly rendered in the NRSV ‘and the dirt came out’; Judges 3:22). The consequent odours may explain why the servants thought he was relieving himself (v.24). The Crusader Bible and Speculum likewise focus on the violent act, even if they do not pay close attention to the details of the text. As guts spill out and blood splatters across the pages, it is the gore that is the subject of these depictions.

In stark contrast, Ford Madox Brown’s engraving focuses only on the potential for violence. Eglon’s size is implied, but not overstated. Eglon begins to rise from his throne while looking at Ehud. Even as Ehud offers a word of God, the viewer’s eye is drawn to the concealed dagger, about to be unsheathed. By freezing the action just before the explosion of gore, Brown opens up the narrative for ethical reflection—is Ehud’s assassination of Eglon congruent with the way of YHWH? Furthermore, Brown’s (misguided) attempt to situate Eglon within the ancient Near East rather than the contemporary medieval world of the Crusader Bible and Speculum arguably humanizes the villain by providing him with a more defined and ‘realistic’ backdrop.

Interestingly, it is Eglon’s deed, rather than Ehud’s, that is central in ancient and medieval Jewish interpretation. Ruth Rabbah 2.9 explains that because Eglon stood to hear God’s word, God granted kingship to Eglon’s descendants via his daughter Ruth. In this tradition, as in Brown’s engraving, Eglon is not reduced to a mere villain.

These perspectives and depictions reveal that, by contrast with modern readers, not everyone considered Ehud’s left-handedness and Eglon’s size to be of central importance to the story.

Like the great art it inspired, this narrative resists over-simplification and may provoke deep ethical and theological reflection on the nature and necessity of violence to effect liberation.

References

Christianson, Eric S. 2003. ‘A Fistful of Shekels: Scrutinizing Ehud’s Entertaining Violence (Judges 3:12–30)’, Biblical Interpretation, 11.1: 53–78

Gunn, David M. 2005. Judges Through the Centuries (Malden: Blackwell Publishing

Sasson, Jack M. (ed.). 2009. ‘Ethically Cultured Interpretations: The Case of Eglon’s Murder (Judges 3)’, in Homeland and Exile: Biblical and Ancient Near Eastern Studies in Honor of Bustenay Oded (Leiden: Brill), pp. 571–95

Stone, Lawson G. 2009. ‘Eglon’s Belly and Ehud’s Blade: A Reconsideration’, Journal of Biblical Literature, 128.4: 649–63

Commentaries by Brandon Hurlbert