Judges 14

Samson and the Lion: Of Honey, Heaven Sent

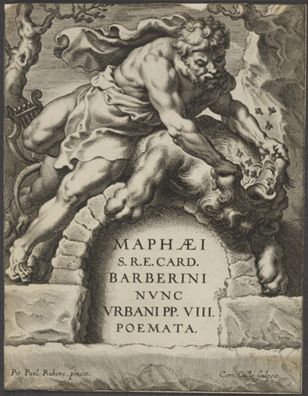

Cornelis Galle I after Peter Paul Rubens

Samson strangling the lion, frontispiece to an edition of the poems written by Urban VIII before his pontificate 'Maphaei S.R.E Cardinalis Barberini Nunc Urbani P.P. VIII Poemata', 1634, Engraving, 176 x 137 mm, The British Museum, London; 1858,0417.1249, Photo: ©️ The Trustees of the British Museum / Art Resource, NY

Ex ore leonis

Commentary by Laura Popoviciu

Cardinal Maffeo Barberini’s (the future Pope Urban VIII’s) collection of Latin poems inspired by biblical themes appeared in fifteen editions during his lifetime. Among these, the one published in Antwerp in 1634 includes a frontispiece with a striking illustration of Samson and the lion, designed by Peter Paul Rubens and engraved by Cornelis Galle I. Why did Rubens choose this iconography for his design, and how does it relate to the content of the publication or the author of the Poemata?

Rubens had already explored the subject of Samson’s fearless encounter with the young lion in a 1628 painting (now in Madrid). Here, he captures the moment when Samson revisits the lion he has killed. As he touches the animal, forcing its jaws open, bees spring out of its mouth.

In the context of the Poemata, the presence of bees invites multiple interpretations. For example, their triangular grouping above Samson’s muscular left arm in this engraving evokes the positioning of the heraldic bees on the coat of arms of the Barberini family.

They also have specifically christological associations. Since antiquity, scientists, philosophers, and theologians have attempted to explain the myth of the spontaneous generation of bees from the corpses of animals, a phenomenon known as bugonia. The apparently miraculous generation of life could function as a metaphor for virgin birth and also for resurrection. A painting, now untraced, is listed in the Barberini inventories with the title Virgin and Child with ‘bees coming from mouth of Madonna’. And Samson’s subjugation of the lion, and the subsequent generation of bees, has been interpreted as a prefiguration of Christ’s triumph over death, and the new life that follows from it.

The visual and textual material relating to the biblical story complement each other in the Poemata. In a poem dedicated to his deceased brother Antonio, Maffeo writes that ‘like Samson, [Antonio] receives sweet honey from the mouth of a slain lion’ (Barberini 1634: 254). The gift of honey thus becomes an emblem and foretaste of the life of heaven.

The associations could be political as well as personal. As an emblem of the resurrected Christ, the virtuous bees reinforce the divine right to papacy, guiding Maffeo’s mission as Pope Urban VIII. His military quest to extend the papal dominions and gain his own independence from Italy has moral echoes of Samson’s mission to free the people of Israel from the Philistines.

References

Barberini, Maphaei. 1634. Poemata (Antverpiae: ex officina Plantiniana Balthasarus Moreti)

Judson, J. Richard and Carl van de Velde. 1978. ‘Book Illustrations and Title pages’, in Corpus Rubenianum, 21.1 (London and Philadelphia: Harvey Miller), pp. 283–87

Lavin, Marilyn Aronberg. 1975. Seventeenth-century Barberini documents and inventories of art (New York: New York University Press), pp.53, 555, Doc. 405 (1636)

Reichman, Eric. 2012. ‘The Riddle of Samson and the Spontaneous Generation of Bees: The Bugonia Myth, the Crosspollination that Wasn’t, and the Heter for Honey That Might Have Been’, in Essays for a Jewish Lifetime: Burton D. Morris Jubilee Volume, ed. by Menachem Butler and Marian E. Frankston (New York: Hakirah Press), pp. 1–12

Bill Woodrow

Fingerswarm, 2000, Bronze with gold leaf, 58 x 35 x 31 cm, Royal Academy of Arts, London; 08/2850, ©️ Royal Academy of Arts, London; Photographer: Paul Highnam

The Next Move

Commentary by Laura Popoviciu

Three bronze fingers emerge from a golden conglomerate. There is no protective equipment to be seen, and no indication of who would dare to penetrate this swarm of bees from within and (in one case) reach out towards the pot of what might be honey: plentiful, nourishing, sweet.

Bill Woodrow’s sculpture Fingerswarm is part of a series he began to develop in 1996 after attending a beekeeping course during which he held a swarm in his bare hand: ‘it was a very light, delicate touch’. It was also, he said, ‘warm’ (RA Collection).

On the face of it, Woodrow’s sculpture teases us into an idealized narrative—an innocent (sweet, even) scene of discovery and creaturely cohabitation—only to caution us gently about the dangers of climate change. In looking at the carefully shaped bees, and despite their apparent multitude, their stillness invites us to reflect on their decline. Woodrow’s provocation to us as viewers is to learn from the past about how to care for the future—a fine balancing act, like that of the three fingers.

We can anticipate the swarm’s next move as one that might, in key respects, replicate that of the bees emerging out of the lion’s mouth. A simple tap, just like that of the instructor on the beekeeping course when he transferred the swarm onto the sculptor’s bare hand, and the bees might suddenly relocate.

Acts of transferral are also part of this sculpture’s history. In 2000, Fingerswarm was included in an exhibition organised by the Victoria & Albert Museum, London which placed contemporary sculptures in six different households on a rotational basis across a period of six months. Described as a ‘contemplative encounter’, this initiative sought to mediate the experience of living with a work of art, and, in the case of Woodrow’s sculpture, to enhance the symbiotic relationship between humans and bees. Invited to reflect on this experience, only one participant connected Woodrow’s sculpture with Samson’s story:

I imagine a whole body inside it, not just an arm. ‘Out of the strong came forth the sweet’. A riddle that Samson used when he found the honey inside the lion.

It was there, perhaps, in that household, that the delicate swarm found itself at least partially ‘unriddled’, disclosing new aspects of its discreet yet transformative message.

References

Kelly, Julia and Jon Wood. 2013. ‘The Beekeeper’, in The Sculpture of Bill Woodrow (Farnham: Lund Humphries), pp. 166–85

Painter, Colin. 2001. Close Encounters of the Art Kind: Work by Tania Kovats, Langlands and Bell, Sarah Lucas, Keir Smith, Richard Wilson, Bill Woodrow (London: Victoria & Albert Museum)

Wood, Jon. 2002. ‘Bill Woodrow interviewed by Jon Wood’, National Life Stories Collection: Artists’ Lives, (London: British Library), parts 29–30

n.d. ‘Fingerswarm, 2000’, RA Collection: Art. Available at: https://www.royalacademy.org.uk/art-artists/work-of-art/fingerswarm [accessed 10 July 2023)

Susan MacWilliam

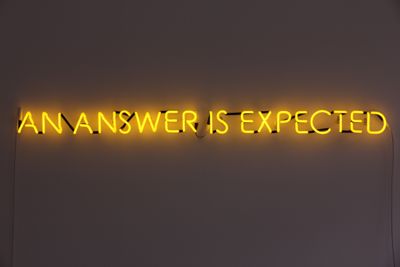

AN ANSWER IS EXPECTED, 2013, Yellow gold neon, Collection of the artist; ©️ Susan MacWilliam, Courtesy of Susan MacWilliam

Unriddled with Taste

Commentary by Laura Popoviciu

Imperative and incisive, Susan MacWilliam’s neon work is a thought-provoking piece. Capitalized letters radiating honey-coloured light emit a puzzling demand: ‘AN ANSWER IS EXPECTED’. What is it that we are being urged to answer with such urgency? Where do we begin to search for the answer?

MacWilliam’s yellow-gold neon is part of a wider body of work comprising sculpture, video, and photography, and investigates extra-sensory perception and telepathy.

The field of parapsychology was pioneered by the American botanist Joseph Banks Rhine (1895–1980), among others, as an alternative to conventional ways of seeking answers and proof. MacWilliam’s interest in Rhine’s experimental research led to a residency at the Rhine Research Centre and Parapsychology Laboratory, housed at Duke University, in 2011. A 1934 telegram found in the archives with a note demanding ‘AN ANSWER IS EXPECTED BY THE SENDER OF THIS MESSAGE’ inspired the title of this work.

The publication which resulted from MacWilliam’s archival research includes transcripts of recorded interviews with Rhine’s group of researchers in the 1970s. One statement made in 1978 by Louisa, Rhine’s wife, stands out:

What you really want to do is find out the answer to this question. This question. This question of whether there is anything more to the human spirit, to the human individual than his physical body. (MacWilliam 2017: 24)

The question is as challenging in its own way as Samson’s riddle addressed to the Philistines: ‘Out of the eater came something to eat. Out of the strong came something sweet’ (Judges 14:14).

Samson’s riddle—formulated to disguise meaning—derives from a private experience revealed by the Spirit of the Lord, and accessible to him alone. Anyone seeking to answer it without having shared Samson’s experience—and in the absence of telepathic power—must surely take on an impossible task.

Yet the eventual rejoinder offered to Samson by the Philistines shows they have found it out. Threatened with death, Samson’s wife has extracted the secret from him and revealed it to his enemies.

This apparently life-saving answer is offered teasingly as a further question—almost another riddle: ‘What is sweeter than honey? What is stronger than a lion? (Judges 14:18).

But it is no riddle for Samson, and—for the Philistines—it is the very opposite of a life-saving answer. Indeed, the consequences of accessing it through deception, and without the guidance of the Spirit of the Lord, are devastating.

References

Eynikel, Erik. 2006. ‘The Riddle of Samson: Judges 14’, in Stimulation from Leiden, vol. 54, ed. by Hermann Michael Niemann and Matthias Augustin (Leiden: Peter Lang), pp. 45–54

MacWilliam, Susan. 2017. An Answer is Expected (Washington DC: Connersmith)

_______. 2019. Modern Experiments (Banbridge: F. E. McWilliam Gallery & Studio)

Cornelis Galle I after Peter Paul Rubens :

Samson strangling the lion, frontispiece to an edition of the poems written by Urban VIII before his pontificate 'Maphaei S.R.E Cardinalis Barberini Nunc Urbani P.P. VIII Poemata', 1634 , Engraving

Bill Woodrow :

Fingerswarm, 2000 , Bronze with gold leaf

Susan MacWilliam :

AN ANSWER IS EXPECTED, 2013 , Yellow gold neon

‘Eat honey, my son, for it is good’

Comparative commentary by Laura Popoviciu

Eat honey, my son, for it is good (Proverbs 24:13)

Animated by an extraordinary strength, Peter Paul Rubens’s Samson rips the lion’s jaws open, asserting himself over the inanimate, cold carcass. On the contrary, Bill Woodrow’s swarm requires a cautious and delicate handling, and we may imagine the bees seductively warm to the touch.

Both acts are performed with bare hands: while Samson’s hands take away, the bronze fingers offer support.

A sense of expectation—as though for a long-awaited answer—attends both artworks as they give hints of what each receptacle contains. The contents of the bronze pot next to Woodrow’s swarm (into which the finger dips) can only be grasped once we draw near it. We become like Samson approaching the lion’s carcass. A mystery of transformation is about to begin; new life emerges in the form of bees and their sweet viscous honey. Just as Susan MacWilliam’s honey-coloured neon lights up like the sun against a dark background—bearing witness to human curiosity and the quest for proofs—the cave-like interior of the lion’s body yields up its golden secrets.

Samson’s name in Hebrew derives from shemesh which means ‘the sun’, and the place of his birth, Zorah, translates as ‘the place of wasps’. In his Poemata, Maffeo Barberini wrote an epigram dedicated to the sun and the bee that reads: ‘In coating with wax the lighted torches, the bee, like the Sun, dispels the shadows with light’ (Barberini 1634: 143).

The process of ‘coating with wax’ also played a central role in the making of Woodrow’s sculpture. First, the artist made a prototype of the swarm using plasticine. Then, he made a wax mould from the basic shape. Finally, he used the traditional lost-wax method to create the bronze sculpture: by pouring molten metal into the mould, the hot liquid displaced the wax by evaporating it.

The fingers and small pot (made separately and attached later) also depend on the use of wax, which coats the surfaces that are to be cast, fitting itself to their shapes. The little honeypot’s shape is reminiscent of that of the crucible used by the sculptor to pour the molten wax into the mould as a preliminary stage in the process of obtaining the bronze version. As it solidifies, the wax seals forever the gesture of the finger dipped into honey.

Some of the tensions as well as intersections which define the association of these artworks help to place Samson as a figure of contrasts, as someone who sits at the crossroads of cultures. He is an Israelite who mixes with the Philistines. He seeks to intensify such encounters by demanding a Philistine wife despite his parents’ advice against it. As a Nazirite, he is not to come into contact with a corpse nor with wine; yet we find him in the vineyards of Timnah and scooping honey out of the carcass of a lion. We find him at his wedding feast promising festal garments to the Philistines in exchange for a correct answer to his riddle.

When Samson presents the riddle, we can, certainly imagine him stating ‘AN ANSWER IS EXPECTED’, commanding the Philistines to come up with the solution in seven days. This answer arrives through deceptive means before the end of the last day. When the sun sets (a moment that is echoed whenever the light of MacWilliam’s neon work goes off), Samson’s wrath against the Philistines begins to show.

The three artworks chosen here to help explore the text of Judges 14 can be viewed as an allegorical feast of the senses: Samson follows his eyes to confront the lion, he smells, touches, and eats the honey, and finally—with burning ears—he hears the answer to his riddle.

Then—like the bees who must reconfigure and relocate—he makes his next move.

References

Carozza, Gianni, 2019. La parola è più dolce del miele. Le api e il miele nella Bibbia e nella tradizione Cristiana. (Padova: Edizioni Messagero)

Eynikel, Eric and Tobias Nicklas (eds). 2014. Samson: Hero or Fool? The Many Faces of Samson (Leiden: Brill)

Franke, John R. (ed.). Joshua, Judges, Ruth, 1–2 Samuel, Ancient Christian Commentary on the Scripture, vol. 4, (Illinois: InterVarsity Press), pp. 147–50

Commentaries by Laura Popoviciu