1 Corinthians 11:17–33

Discerning the Body

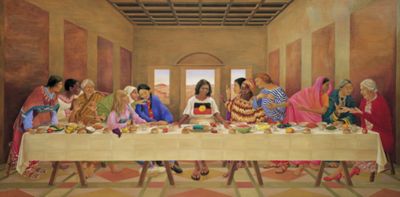

Susan Dorothea White

The First Supper, 1988, Acrylic on panel, 120 x 240 cm; ©️ Copyright Agency. Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York, 2021; Photo: Courtesy of the Copyright Agency

‘I Hear There are Divisions Among You’

Commentary by Joelle A. Hathaway

Lack of social and spiritual unity at the Lord’s Table is the central concern Paul is confronting in 1 Corinthians 11:17–33. Australian artist Susan Dorothea White’s painting The First Supper illuminates painful gender, racial, and ethnic divisions that exist in both the church and Australian society.

The composition of The First Supper is modelled on Leonardo da Vinci’s mural of The Last Supper (1492–97/8) depicting the moment after Jesus’s declaration ‘Truly I tell you, one of you will betray me’ (Matthew 26:21 NRSV). White’s painting challenges ‘the acceptance of the image of thirteen men … as a celebrated symbol of a patriarchal religion’ (White 1988). Instead, we are presented with an image of ethnic and racial diversity.

The woman who occupies the place where Jesus sits in Leonardo’s original is an Australian Aboriginal woman, gesturing welcomingly towards the traditional food of her people (witchetty grubs, a blue-green emu egg, nuts, and quandongs [a desert fruit]). The twelve ‘disciples’ are women in traditional dress (except the white woman), from around the world. They represent the various peoples who have become part of Australian society. The woman sitting in the position of Leonardo’s Judas is the only person of white European descent; in front of her is a hamburger and Coke, representing the commodification and economic exploitation central to the colonial project. Paul’s admonition to the Corinthians might seem applicable to her (for all the other women have a bread roll and a glass of water, in common with each other):

When you come together, it is not really to eat the Lord’s supper. For when the time comes to eat, each of you proceeds to eat your own supper… (vv.20–21 NRSV)

This work was painted partially in response to the Australian Bicentennial of 1988, which was a celebration of the 200th anniversary of the arrival of English settlers to Australian shores. Many Aboriginal people saw this as a celebration of white invasion and the devastation of their culture. This conflict is referenced by the Aboriginal Christ-figure’s shirt, which displays the Aboriginal Land Rights flag. Also visible through the window on her right side is the sacred Aboriginal site Uluru, which had recently been returned by the government to the Aboriginal people.

The supper is ‘first’ in that the arrival of English settlers is the ‘first’ moment of a more diverse Australia, but also of a more divided one.

References

White, Susan Dorothea. 1988. Artist’s notes on The First Supper, available at http://www.susandwhite.com.au/enlarge.php?workID=94 [accessed 1 October 2020]

Graeme Mortimer Evelyn

Reconciliation Reredos, 2011, MDF and paint, St Stephen's Church, Bristol, UK; ©️ Graeme Mortimer Evelyn, Image courtesy the artist

‘Proclaim the Lord’s Death Until He Comes’

Commentary by Joelle A. Hathaway

When Jamaican-British artist Graeme Mortimer Evelyn was commissioned to design a contemporary altarpiece for the high altar of St Stephen’s Church, Bristol, he became the first Black British artist to complete such a commission in Europe. The work was to respond to the city’s commemoration of the bicentenary of the 1807 Act to Abolish the Slave Trade and to reflect on the concepts of creation, Imago Dei, reconciliation, and hope (Higgins 2011: 1).

Evelyn’s work was designed to be incorporated in a preexisting nineteenth-century reredos, around a central stone relief of the Lamb of God. His four large fibreboard panels replaced four Victorian ones that were made of tin and that (having become corroded) were beyond repair. Each of Evelyn’s panels was hand-carved in relief and then painted in bold colours—black, red, yellow, green, and blues.

The gaze of the inner two figures draws the viewer’s eye to the Lamb of God carving and to the stained glass above, where Christ is enthroned. They underscore the commission’s concern with how a path of reconciliation is opened between creatures and God, and how the image of God is restored in them.

The figures in the outer panels are looking outward and forward: that in chains on the left signifies ‘Creation’, enslaved to sin but undergoing liberation; that on the right, Stephen (first Christian martyr and patron saint of the church) to whom heaven is opened. He embodies hope. The rays from all four panels draw one’s eye down to the eucharistic altar below, and out to the city beyond.

Just as Bristol’s history played a key role in the work’s conception, it is central to what the work invites continued reflection upon. The city was a major harbour for the English side of the transatlantic Slave Trade. As the harbour church, St Stephen’s blessed every merchant vessel before its voyage, including the slave ships. It benefitted from the merchants’ donations, and served as the burial site for Africans living in Bristol in the era of the Trade.

This reredos calls attention to the issue of social inequality that Paul is critiquing in 1 Corinthians 11:17–33. He writes to the Corinthians in verse 28: ‘examine yourselves, and only then eat of the bread and drink of the cup’. Evelyn’s work calls the church to examine its racial past and the ramifications of that past on the Lord’s Supper in the present.

References

Higgins, Tim. 2011. Reconciliation Reredos, pamphlet for St Stephens Bristol, UK, p. 1

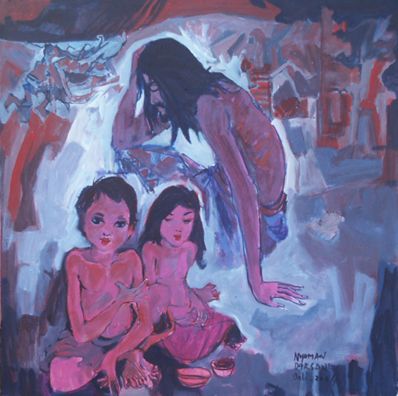

I Nyoman Darsane

Empty Stare, 2004, Acrylic on canvas, 82.55 x 73.66 cm, Collection of artist; ©️ I Nyoman Darsane; Photo courtesy of the artist

‘You Humiliate Those Who Have Nothing’

Commentary by Joelle A. Hathaway

On more than one occasion, contemporary Balinese artist Nyoman Darsane has depicted Jesus sharing a space with two children. This example, entitled Empty Stare, was painted in the year of the Indonesian tsunami in 2004, whose devastating effects accentuated the inequality and destitution that afflict innumerable vulnerable people in that region (Pongracz 2007: 26).

The viewer is confronted by the gaze of two hungry and poorly clothed children. The boy’s knee and an empty bowl have been pushed to the front of the picture plane so that they appear to be sharing the same space as the viewer. Positioned behind the boy and girl sits a dejected Jesus with his head in his hands. He is clothed in a comparable way to the children.

The painting emphasizes Jesus’s solidarity with the poor, and in particular the ‘little ones’ (Matthew 18:6) among them, for whom he has special compassion.

In 1 Corinthians 11:21 Paul chastises the Corinthians for the way the rich are going ‘ahead with [their] own supper’ (NRSV). In doing so, they are ‘show[ing] contempt for the church of God and humiliat[ing] those who have nothing’ (1 Corinthians 11:22). This is the sort of division to which these children attest.

Empty Stare addresses the Bible’s messages about need, want, and exclusion to contemporary society. Paul’s stark claim is that those who profane the ritual body at the Lord’s Supper by neglecting the poor ‘eat and drink judgment upon themselves’ (v.29). The claim has a powerful visual charge added to it by the way that the children in Darsane’s composition, with their empty bowls and empty hands, are on the very threshold of the painting; almost in our own space. The impression that we might be bringing judgement on ourselves by the way we relate to them becomes vivid.

References

Pongracz, Patricia C. 2007. ‘Religious or Aesthetic Lessons? The Bible Illustrated by Asian Artists’, in The Christian Story: Five Asian Artists Today, ed. by Patricia C. Pongracz, Volker Kuster, and John W. Cook (New York: Museum of Biblical Art), pp. 26–27

Susan Dorothea White :

The First Supper, 1988 , Acrylic on panel

Graeme Mortimer Evelyn :

Reconciliation Reredos, 2011 , MDF and paint

I Nyoman Darsane :

Empty Stare, 2004 , Acrylic on canvas

‘Eating Worthily’

Comparative commentary by Joelle A. Hathaway

Considering what it means ‘to come together’ as Church in today’s tumultuous world is an urgent necessity. These three contemporary works of art were chosen as small windows onto the pressing issues of global poverty, gender discrimination, and ethnic and racial oppression. Read in conversation with Paul’s concerns for the celebration of the Lord’s Supper in 1 Corinthians 11:17–34, they invite us to consider various challenges to the unity of the body of Christ.

1 Corinthians 11:27–28 is often read as an exhortation to individuals to consider their worthiness to receive the Eucharist. For, it says, whoever eats the bread and drinks the cup in ‘an unworthy manner’ (NRSV) or ‘unworthily’ (KJV), will be ‘answerable to’ (NRSV) or ‘guilty of’ (KJV) ‘the body and blood of the Lord’. Separated from the larger context of 11:17–34 it may seem to be speaking about individual sin, but this interpretation truncates the radical communal thrust of Paul’s argument.

This section begins with Paul’s condemnation of the events he hears are occurring at the Lord’s Supper in Corinth: that some members are gorging on large portions of food and drink while the poor members go hungry. In this division between rich and poor, the rich are showing contempt for the Lord’s table and humiliating their poor brothers and sisters. This is the key injustice that Paul is concerned to confront.

The ‘body’ that the Corinthians are called to discern and examine is the body of Christ: the social body of the Church as it is shaped and animated by the Spirit which Christ bestowed on it. As Paul has argued in the previous section, the Church is ‘one loaf’ (1 Corinthians 10:16–17 NRSV), and eats and drinks ‘for the glory of God’ (v.31). His use of the words of institution is designed to emphasize that it is the Lord’s supper the Corinthian congregation is eating. It is a perpetual commemoration and proclamation of the death that has won for them entrance into a new spiritual, social, and political reality. The point of the meal is lost in the division between rich and poor. The Corinthians are unable to witness to the salvation that makes them one; this is their guilt (Fee 1987: 560–61).

Instead, Paul calls them to ‘wait for one another’ (vv.33–34). Gordon Fee expands the nuance of this phrase to include ‘receive’, ‘welcome’, and ‘accept’ one another (1987: 567). Waiting for one another to eat the meal and eating the same meal is important, but this waiting is intended to signify a deeper reception and hospitality of the other.

What does it mean, then, to eat worthily in our current economic, social, and political climate? The three works of art address this question in different ways. The First Supper takes a famous and beloved image of Jesus with his disciples and turns it on its head. It invites Christian viewers to ask: who is welcomed at the table?; who is offered leadership?; how can the church concretely reckon with exploitative colonial histories? If one is white: what does it mean to see oneself in the seat of Judas, the betrayer?

The poignant image of Empty Stare confronts the viewer with those who are hungry while they—the ‘rich’ in the Corinthian church to which Paul was writing—potentially go forward with their lives without waiting for or welcoming the poor. In this image Jesus is on the side of the excluded. He sits in solidarity with those who have been pushed to the margins of society—even to the margins of the Church—and calls for the Church to be in solidarity as well.

Reconciliation Reredos brings the question more specifically to the eucharistic table. Located directly behind the high altar, this brightly coloured work confronts us with a division (the legacy of slavery), proffers hope for reconciliation (the Lamb of God), and points toward an enactment of Christian hospitality with one another in the eucharistic elements of the body of Christ.

Coming together to eat the Lord’s Supper worthily, so that it is a true proclamation of unity in Christ, will require the Church actively to confront the powers of this world that divide people by race, nation, ethnicity, and socio-economic status. Only when we are truly able to accept, receive, and welcome one another will our communions truly witness to the Lord’s Supper.

References

Fee, Gordon. 1987. The First Epistle to the Corinthians (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans), pp. 560–61, 67

Commentaries by Joelle A. Hathaway