John 1:32–39

Agnus Dei

Unknown English artist

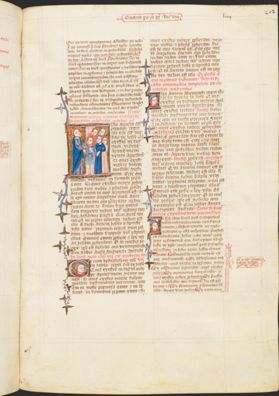

Christ speaks to the multitudes about John the Baptist, from a 'Commentary on the Gospels' by William of Nottingham, 14th century, Illuminated manuscript, Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford; MS Laud Misc. 165, fol. 202r, Photo: © Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford

A Priestly Baptist

Commentary by Melanie McDonagh

This illumination is from a mid-fourteenth-century manuscript (William of Nottingham’s commentary on Clement of Lanthony’s gospel harmony, Unum Ex Quattuor). After being owned by James Palmer (who wrote part of it), it was acquired by Thomas Arundel (1353–1414), Archbishop of Canterbury.

This particular image relates not to the Gospel of John but to the passage in Matthew 11:7 in which Christ addresses the multitude about John. I include it here to show that at whatever stage the Baptist is depicted by artists, we are likely to find him with his lamb.

It is because the Lamb of God is the Baptist’s description of Christ in John 1:36 that it becomes one of his own defining symbols. Along with his camel hair and bare feet the lamb is one of his most recognizable visual attributes. Here it is enclosed in a medallion—to which he points with his finger as we are told he pointed to Christ with the words, Ecce Agnus Dei (‘Behold, the Lamb of God’).

In medallion form, the Agnus Dei is also suggestive of the Eucharist—the Ecce Agnus Dei from John 1:36 is recited at Mass at the point the priest raises the consecrated host. This association between the words of John the Baptist and the sacrament itself is, I think, one reason why the Baptist is often associated with the Eucharist. It is borne out in a hostile account of a Corpus Christi procession by Thomas Naogeorgus, translated by Barnaby George: ‘St John before the bread doth go, and pointing towards him / Doth show the same to be the Lambe that takes away our sinne’ (Hutton 1994: 129).

John here is not dressed in his traditional camel’s hair—interestingly, given that in the passage being illustrated Christ explicitly says that John did not dress in soft clothes (Matthew 11:8)—but his identity is nevertheless apparent from his bare legs and feet, which refer to his wilderness existence.

Note that John here, at centre, is smaller than Christ, whom we see on the left. This may refer to John’s pronouncement (John 3:30) that ‘he [Christ] must increase and I must decrease’. Several medieval commentators (for instance, Ryan 1993: 336) observe that this was borne out by their deaths, with Christ raised on the cross, and John diminished by a head.

References

Hutton, Ronald. 1994. The Rise and Fall of Merry England: The Ritual Year 1400–1700 (Oxford: Oxford University Press)

McDonagh, Melanie. 2001. ‘Devotion to St John the Baptist in England in the Middle Ages’, PhD dissertation, University of Cambridge, pp. 183–86

Ryan, W. G. (trans.). 1993. Jacobus de Voragine: The Golden Legend, vol. 1, (Princeton: Princeton University Press)

Unknown English artist

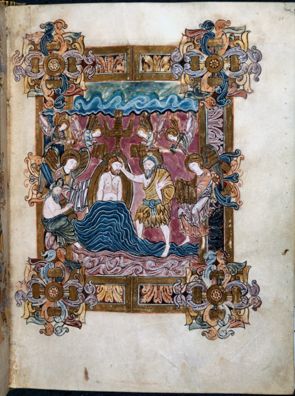

The Baptism, from The Benedictional of St Æthelwold, 963–84, Illuminated manuscript, 290 x 225 mm, The British Library, London; Add MS 49598, fol. 25r., © The British Library Board (Add MS 49598, fol. 25)

Making (a) Way

Commentary by Melanie McDonagh

This illumination is from the celebrated Benedictional of St Æthelwold, produced at Winchester or Thorney for the personal use of the bishop by the scribe Godeman.

Godeman describes how Æthelwold, ‘whom the Lord had made patron of Winchester’, commanded that the book should have ‘many frames well adorned and filled with various figures decorated with many beautiful colours and with gold’ (fol. 4v–5).

This illumination confirms that description, with its shimmering gold leaf, vibrant colours, exuberant imagery, and flowing lines. Its subject recalls John 1:32–33 in which the Baptist describes how he saw the Holy Spirit descend ‘as a dove’ and come to rest on Christ. The other three Gospels make plain that this descent took place during the baptism of Christ.

As often in this scene, angels wait upon Christ with towels or perhaps robes. John is shown dressed in animal skin (a typical interpretation of Mark 1:6 and Matthew 3:4’s references to ‘camel hair’, and an effective visual shorthand for signalling the identity of this desert-dwelling saint). He is touching Christ with his right hand—and this, as we shall see, is important—while his raised left hand displays its open palm. The Baptism was celebrated on the feast of the Epiphany in addition to the coming of the Magi, and in the Benedictional this illumination precedes the benediction for the Epiphany. (The image before it—fol. 24v—is of the Magi.)

The horned figure on the left in the posture of a river god probably represents Moses (Lester 1973: 32–33). As the embodiment of the Old Law that was being replaced by the New, in Christ, he is planted firmly on the left bank of the Jordan, whose waters he pours out.

Moses, we recall, never got to cross this river (Deuteronomy 3:23–29). Yet he was vouchsafed a vision of God (Exodus 33:11; 34:5–7). The Baptist too sees the divine mysteries: ‘I saw the Spirit descend…’ (John 1:32); ‘I have seen … that this is the Son of God’ (v.33). And here we see the Spirit in the form of a dove descending on Christ.

References

Lester, G.A. 1973. ‘A Possible Early Occurrence of Moses with horns in the Benedictional of St Æthelwold’, Scriptorium, 27: 1

McDonagh, Melanie. 2001. ‘Devotion to St John the Baptist in England in the Middle Ages’, PhD dissertation, University of Cambridge

Unknown artist [Paris]

John the Baptist Testifying the Nativity to the People, from a Franciscan Misssal, Mid-14th century, Illuminated manuscript, Bodleian Libraries, The University of Oxford; MS Douce 313, fol. 17r, Photo: © Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford

The First Witness of the Trinity

Commentary by Melanie McDonagh

This depiction of John the Baptist preaching to the people and pointing to the infant Christ in the manger is from a mid-fourteenth century Franciscan missal produced in Paris. It is illuminated in grisaille (shades of grey) with coloured tints, reflecting contemporary taste for monochromatic work, which could be executed relatively economically.

In the margin is the symbol of John the Evangelist, the eagle, referring us to that Gospel. The baby is attended by the beasts traditional in Nativity scenes—and of course it was St Francis who first gave us the manger scene with its ox and ass.

An illumination that appears prior to this one in the manuscript (folio 10) also depicts John preaching—he is shown standing at the Jordan, as we might expect from the Gospel accounts. (In medieval accounts, he is classed as preacher as well as prophet and martyr.) The familiarity of that scene contrasts sharply with the apparent oddity of this one. According to the Gospel of Luke, John the Baptist was six months older than Christ. Here, he appears alongside the Christ child as adult.

This is a conscious anachronism. It can be read as a fleshing out of John 1:33–34, ‘And I have seen and have borne witness that this is the Son of God’.

The Son of God was manifest in flesh as the infant Christ. The Baptist sees and knows and (uniquely in John’s Gospel) witnesses to this ‘lamb’, who is to ‘take away the sin of the world’. And because it is a destiny Christ bore from his birth, John is here shown pointing to him as a baby. (Earlier in the story, at the Visitation, commentaries and images describe the unborn John greeting the foetal Christ.)

This in turn reflects one of the privileges of the Baptist according to Christian tradition, namely, that he was the first to whom the doctrine of the Trinity was revealed (McDonagh 2001: 82). John saw the Spirit as dove and heard the Father’s voice (God the Father is shown speaking to John from heaven both here and on fol. 10). But in this illumination the point is even more explicit. The word ‘Deus’ on the band refers not just to the Father but to the infant below. We are pointed by the Baptist to the triune God present in both the infant Christ and the Father in Heaven.

Unknown English artist :

Christ speaks to the multitudes about John the Baptist, from a 'Commentary on the Gospels' by William of Nottingham, 14th century , Illuminated manuscript

Unknown English artist :

The Baptism, from The Benedictional of St Æthelwold, 963–84 , Illuminated manuscript

Unknown artist [Paris] :

John the Baptist Testifying the Nativity to the People, from a Franciscan Misssal, Mid-14th century , Illuminated manuscript

The Pointing Finger

Comparative commentary by Melanie McDonagh

John 1 establishes John the Baptist’s unique character as a prophet unlike any other, the prophet of the present tense; not foretelling the coming of the Messiah, but actually identifying him in the flesh. Viewed in this way, John functions as an intermediary between the old dispensation and the new, between the Old Testament and the New Testament. Augustine describes him as a ‘threshold’ between them, quidem limes veteris et novi Testamenti (Sermon 293, col. 1328; see also McDonagh 2001: 22).

The most notable body part of John the Baptist in the view of medieval commentators was his finger. From the time of Augustine onwards, John is invariably described as pointing with his finger at Christ when he acknowledges him as the Lamb of God. Because of this he was considered to be plusquam propheta (‘more than a prophet’; Matthew 11:9): he does not merely prophesy about the one who is to come in the future, but is able to acknowledge him in person, and express that recognition with a gesture.

The importance of the finger is such that when Julian the Apostate had the bones of the Baptist burned at Sebaste (the head had gone elsewhere), the one part of him that survived—according to the account in the Golden Legend—was that finger.

No surprise, then, that pointing fingers have such prominence in two of the artworks here, and that pointing is the characteristic posture of the Baptist in countless books of hours, paintings, statues, and tapestries, almost all of which show him bare-legged, usually wearing a camel skin, indicating either Christ or his symbol, the lamb.

In the illumination from the Unum ex Quattuor manuscript, the lamb is contained in a medallion. This, resembling a consecrated host, is suggestive of an important element of the medieval cult of the Baptist—his association with the Eucharist. Usually the association is in terms of the head of the Baptist on the plate, representing the paten (the York breviary, in the fourth lesson for the feast of the Decollation, reads: Caput Johannis in disco: signat corpus christi quo pascimur in sancti altari, translated as ‘the head of John on the plate signifies the body of Christ by which we are fed on the holy altar’; Lawley 1883: col. 517). It seems that there is not just a symbolic reason for the association between the Baptist and the Eucharist; there is a liturgical link because priests at Mass still pronounce the words of John, Ecce Agnus Dei (‘Behold, the Lamb of God’), as they display the consecrated bread to the gathered congregation.

The Winchester Benedictional reflects another aspect of the bodily interaction between the Baptist and Jesus as it was imagined by medieval commentators. It was reasonably assumed that John physically touched Christ when baptizing him, just as we see him doing here. One Benedictine homilist emphasized John’s worthiness to baptize Christ et manibus tractare (‘and to touch [him] with his hands’; Cambridge, Trinity Coll. MS B14.48, fol. 76). The physical contact with Christ was itself one of the privileges of John identified by some commentators.

The Franciscan missal from Paris is unusual in that it identifies a further important element in the cult of the Baptist, namely, that he was the first to receive the revelation of the doctrine of the Trinity. In one late-twelfth-century English manuscript, the list of the privileges of the Baptist includes the fact that: ‘[t]he first revelation of the Trinity was to him’ (PL184, 675–81, cols 991–1002, incorrectly attributed to St Bernard), and in this passage of John’s Gospel, he refers to hearing the voice of the Father (in the Synoptic Gospels, the voice speaks of ‘my beloved son’) and seeing the Spirit descend as a dove. The implications of this are spelled out in this illumination where the scroll that links the Baptist and the figure of God the Father says, explicitly, ‘Deus’, while the Baptist points with a finger both to the First Person of the Trinity above him, and to the infant Christ at his feet. In other words, divinity is shown to refer both to Father and Son.

And so, the Baptist’s early recognition of Christ’s divinity is brought right to the manger-side, and the Franciscan devotion to the infant child in the manger, surrounded by the beasts, is brought right into the Gospel narrative of the Baptism. John discerns—and preaches on—the Trinity, just as the friars did.

References

Lawley, S. W. 1883. Breviarium Ad Usum Insignis Ecclesiae Eboracensis, vol. 2 (London)

McDonagh, Melanie. 2001. ‘Devotion to St John the Baptist in England in the Middle Ages’, PhD dissertation, University of Cambridge, p. 22

![John the Baptist Testifying the Nativity to the People, from a Franciscan Misssal by Unknown artist [Paris]](https://images-live.thevcs.org/iiif/2/aw0890_unknown-artist_john-the-baptist-testifying-the-nativity-to-the-people_0.ptif/full/!400,396/0/default.jpg)

Commentaries by Melanie McDonagh