2 Kings 2:12–25

Elisha Begins

Works of art by Gerhard Remisch, Unknown English artist known as the Master of the Leaping Figures and Unknown Netherlandish artist

Unknown English artist known as the Master of the Leaping Figures

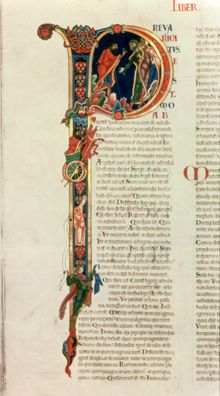

Beginning of Second Kings with historiated initial showing the messengers of Elijah and Ahaziah, from the Winchester Bible, c.1160–75, Manuscript illumination, 583 x 396 mm, Winchester Cathedral Library; fol. 120v, Bridgeman Images

Elisha Receives the Mantle of Elijah

Commentary by Martin O’Kane

Elijah’s mantle, with which he covers his face in the cave (1 Kings 19:13), which he casts over Elisha (1 Kings 19:19), and which he rolls up in order to strike the river Jordan, causing its waters to part (2 Kings 2:8), becomes the symbol of the prophetic authority that the older man passes on to his successor.

As Elisha stands awe-struck at the dramatic departure of Elijah in his chariot of fire, Elijah’s mantle falls—making it the prophet’s only material relic—and Elisha eagerly picks it up. Through its miraculous powers, Elisha is able to perform the same miracle as Elijah, dividing the waters of the Jordan in two (2 Kings 2:13–14).

The symbolic importance of the mantle is exquisitely rendered in the historiated initial P that opens 2 Kings in the Winchester Bible. The artist, known as the Master of the Leaping Figures, creates three dramatic scenes: the cup of the letter P depicts the messengers of the ill King Ahaziah reporting Elijah’s prophecy to him that he shall surely die (2 Kings 1:5–6), while the stem conveys the dramatic swirling of the prophet’s chariot of fire as it moves heavenward (2 Kings 2:11), and Elisha’s excitement as he rushes to seize the garment that falls from his master (2 Kings 2:13–14).

The artist paints the mantle twice, using two of the most precious materials available to him: in the centre, it is depicted in gold with its sleeve raised towards the departing Elijah, and at the bottom in lapis blue as Elisha catches it in his right hand.

The illuminations of the Winchester Bible are celebrated for their ‘damp-fold drapery’, in which material is shown clinging to the human figures like wet cloth, thereby articulating the shapes of their bodies more fully. Here, the illuminator uses his skill to show the golden mantle preserving Elijah’s contours as it falls. It is as though Elijah’s miraculous garment is about to envelop Elisha while still bearing the master’s imprint—clothing Elisha with the physical symbol of his spiritual inheritance and underscoring the link between the two men.

References

Donovan, Claire. 1993. The Winchester Bible (London: The British Library/Winchester Cathedral), pp. 40–41

Gerhard Remisch

Elisha and the Sons of the Prophets, c.1516–22, Stained glass, 70 x 65.9 cm, Victoria and Albert Museum, London; Given by E.E. Cook, C.210-1928, © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Elisha and the Sons of the Prophets

Commentary by Martin O’Kane

The term ‘company of prophets’ (in Hebrew ‘sons of the prophets’) is very infrequent in the Bible and found, almost exclusively, in the story of Elisha. Generally regarded as followers or disciples of the prophet, this group appears in several of the Elisha narratives (e.g. 2 Kings 2:3, 5, 7, 15) and, most significantly, it is they who first affirm that ‘the spirit of Elijah now rests on Elisha’ (2:15).

Despite much discussion regarding the identity of this ‘company of prophets’ in Christian tradition, especially by Protestant Reformers such as Johannes Bugenhagen (1485–1558) and John Mayer (1583–1664), they do not feature significantly in iconography. This makes their appearance in a stained-glass window in the cloisters of the Mariawald Cistercian Abbey in Germany all the more rare.

With his characteristic bald head, we see Elisha being approached by an eager and enthusiastic group of younger men who clearly acknowledge his authority. Elisha discourages them from seeking Elijah (2:16), his caution expressed in his raised hands. He is dressed in the spartan garb of a Cistercian monk which in its simplicity is also reminiscent of the garb attributed to Elijah (1:7)—indeed, both Elijah and Elisha were held up by the Cistercians as models for the monastic life.

Thus the window underscores an affinity between the prophet and the monastic vocation for the edification of its original viewers. It also draws attention to Elisha as a type of Christ. In the original typological arrangement of the windows in the Abbey’s cloisters, this scene prefigured the window that was immediately below it, showing the entry of Christ into Jerusalem, celebrated by the Church on Palm Sunday (Matthew 21:1–11; Mark 11:1–10; Luke 19:29–40; John 12:12–19).

The acknowledgement of the crowds as they welcome Christ’s entry into Jerusalem is prefigured by the proclamation of Elisha as the spiritual successor to Elijah by ‘the sons of the prophets’. In the small tracery panel above their meeting with Elisha, the prophet Ezekiel holds up a scroll relating the Old Testament story to the New Testament, thus giving the typology even greater sanction and authority.

References

Williamson, Paul. 2003. Medieval and Renaissance Stained Glass in the Victoria and Albert Museum (New York: Abrams)

Unknown Netherlandish artist

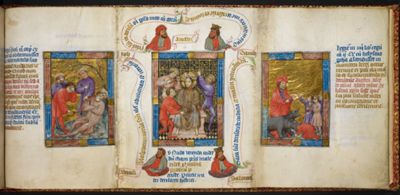

The Drunkenness of Noah; The Mocking of Christ; Children mocking the prophet Elisha, from a Biblia Pauperum, c.1395–1400, Illuminated manuscript, 175 x 385 mm, The British Museum, London; Kings MS 5, fol. 15r, © The British Library Board (Kings MS 5, fol. 15r)

Elisha and the She-Bears

Commentary by Martin O’Kane

He turned around, looked at them and called down a curse on them in the name of the Lord. (2 Kings 2:24)

This incident from the start of Elisha’s career raises many ethical issues. There seems a disproportionate mismatch between punishment and crime.

The variant interpretations of the story in the Talmud suggest that the early rabbinic thinkers were much troubled by the idea of prophet-mocking children being mangled by divinely commissioned bears. For example, Babylonian Talmud Sotah 46b–47a explains that Elisha’s mockers were not boys, but adult water-carriers from Jericho who ‘behaved like little children’.

Christian interpreters, on the other hand, were content to interpret the incident typologically. The explanation of Caesarius, Bishop of Arles (c.470–543 CE), provides a characteristic example, typical of early Christian anti-Jewish interpretations: the insults of the Jewish children prefigure the shouts of the Jews at the crucifixion of Christ (Luke 23:21). The number of boys to be killed, forty-two, was taken to signify the number of years after the death of Christ when two bears—the Roman emperors Vespasian and Titus—besieged and destroyed Jerusalem, punishing the Jewish people for what Caesarius saw as their heinous crime.

As a result of such typological interpretations, the mockery of Elisha became—grimly—a standardized scene in medieval Christian art, most notably in illuminated manuscripts. In this tripartite image in the Biblia Pauperum, a large central panel shows the Jews mocking and taunting Christ, placing a crown of thorns on his head. On either side two smaller Old Testament scenes depict, on the left, the mocking of Noah’s nakedness by his son Ham and, on the right, the summoning of bears by Elisha to devour the boys—one of whom has already been half eaten. The typological parallels are made clear and irrefutable by the inclusion of biblical texts.

References

Ziolkowski, Eric. 2001. Evil Children in Religion, Literature, and Art (London: Palgrave), pp. 36–55

Unknown English artist known as the Master of the Leaping Figures :

Beginning of Second Kings with historiated initial showing the messengers of Elijah and Ahaziah, from the Winchester Bible, c.1160–75 , Manuscript illumination

Gerhard Remisch :

Elisha and the Sons of the Prophets, c.1516–22 , Stained glass

Unknown Netherlandish artist :

The Drunkenness of Noah; The Mocking of Christ; Children mocking the prophet Elisha, from a Biblia Pauperum, c.1395–1400 , Illuminated manuscript

A Multifaceted Prophet

Comparative commentary by Martin O’Kane

The events surrounding the transfer of Elijah’s prophetic powers to Elisha which open 2 Kings are quite sensational: King Ahaziah falls unexpectedly from his upstairs window (1:2), the river Jordan is parted twice (first by Elijah and then by Elisha: 2:8, 14), and Elijah ascends to heaven in a whirlwind in his famous chariot of fire (2:11).

But two episodes are troubling: the callousness with which Elijah calls down fire from heaven to consume King Ahaziah’s troops (twice, 1:10, 12), and Elisha’s impulsiveness in summoning she-bears to maul forty-two boys as a punishment for the trivial offence of simply calling him names (2:23–24).

The images selected for this exhibition exemplify different approaches to depicting Elisha’s multifaceted and contradictory character as he assumes the prophetic authority bestowed on him in such dramatic and unparalleled circumstances.

The earliest of the three artworks discussed here is the historiated initial P from the twelfth-century Winchester Bible. With its swirling, writhing figures, the artist—aptly named The Master of the Leaping Figures—evokes the intense drama and turmoil of Elijah’s final moments on earth, culminating in Elisha grasping the mantle of Elijah as it falls from his chariot. Elijah’s horses and chariot of fire, and the outstretched arms of Elisha as he seizes the falling mantle, seem to spill out beyond the edges of the initial and into the text itself. The urgency and speed with which the two prophets move suggest an impatience and a barely controllable energy. King Ahaziah, by contrast, doomed never to recover from his injuries, is held captive in the enclosed cup of the initial. The Bible was created for the Benedictine monks of the Old Minster of Winchester and the fact that this page is darkened by intensive use, compared with other pages in the Bible, demonstrates its particular appeal through the centuries.

At a later date and in a different medium, we find Elisha depicted for another monastic context in the Cistercian abbey of Mariawald in Germany. In an elaborate series of exquisitely wrought stained glass, the window focusses not on the drama surrounding the start of Elisha’s ministry but rather on that special group of followers called ‘the sons of the prophets’ who, throughout the Bible, are associated almost exclusively with the prophet. Throughout Elisha’s life, they will remain his committed and ardent disciples. Unlike the leaping, dancing figure in the Winchester Bible, Elisha is here represented as someone with a gravitas that the monks might have considered appropriate to his calling. Clothed in the garments of a Cistercian, his appearance evokes one of his many attributes, namely his role, along with Elijah, as an archetype of the monastic life.

Unlike the ornately historiated Winchester Bible, or the stained glass of the wealthy Mariawald Abbey (both painted by professional artists of some repute), the image from the Biblia Pauperum (a picture Bible that represented the typological correspondences between the Old and New Testaments) almost certainly gained more popular currency. The Biblia Pauperum, with its standard presentation of a New Testament subject flanked by two Old Testament scenes, encouraged typological approaches to the Bible, and, in the case of Elisha, drew detailed comparisons between the prophet and Christ. Comparisons could be creative and imaginative, but, often too, they revealed a predisposition to anti-Jewish hostility. The folio from the Netherlandish Biblia Pauperum discussed here demonstrates how the episode of Elisha summoning bears to kill forty-two children was typologically interpreted: the typological approach conveniently equated the boys who mocked Elisha with the Jews who tormented Christ, thus exonerating the prophet from any personal blame or ethical responsibility.

The behaviour of Old Testament prophets could be enigmatic and controversial, and Elisha was no exception. Taken together, the three images in this exhibition portray different aspects of the prophet’s life: the drama and spectacle surrounding the start of his ministry, represented in the historiated initial; the dignified figure of authority advising his disciples in the Mariawald stained glass; and the irritable and impetuous actions of ‘a man of God’ (his questionable behaviour neatly side-stepped by the use of convenient typological parallels) in the Biblia Pauperum.

To us today, the behaviour of Old Testament prophets may seem enigmatic and controversial, and Elisha is no exception. The three images in this exhibition reflect centuries of theological interpretation that strove to make the prophet meaningful and relevant to times and circumstances different from our own. That all three present quite different aspects of Elisha’s character—flamboyant, contemplative, or impetuous—is an encouragement to imagine biblical figures, and not just Elisha, in ways appropriate to (even while sometimes challenging of) our own settings.

References

Edden, V. 1999. ‘The Mantle of Elijah: Carmelite Spirituality in the Fourteenth Century’, in The Medieval Mystical Tradition: Exeter Symposium IV, ed. by M. Glasscoe (Cambridge: D.S. Brewer), pp. 67–84

Ziolkowski, E. 1991. ‘The Bad Boys of Bethel: Origin and Development of a Sacrilegious Type’, History of Religions 30.4: 331–58

Commentaries by Martin O’Kane