1 Thessalonians 5:1–11

Faith, Hope, and Love

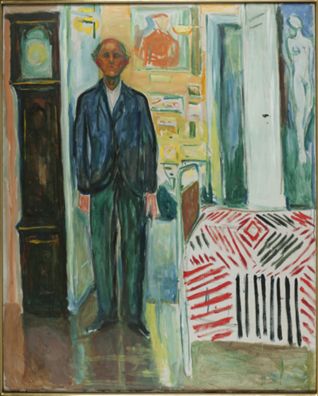

Edvard Munch

Self-Portrait between the Clock and the Bed, 1940–43, Oil on canvas, 149.5 x 120.5 cm, Munchmuseet, Oslo; M 23, © The Munch Museum / The Munch-Ellingsen Group / Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY HIP / Art Resource, NY

Be Alert

Commentary by Daniel Siedell

We are not of night nor of darkness … be alert…. For those who sleep do their sleeping at night, and those who get drunk get drunk at night’ (1 Thessalonians 5:5–7 NASB)

In a journal entry early in his career Edvard Munch wrote, ‘I paint my soul’s diary’ (Tøjner 2003: 135). With this self-portrait, painted at the end of his life, we recognize that the artist’s soul is and has been a lonely one—and haunted by the spectre of death, the deaths of his mother and older sister, and the horrors of World War I.

Munch appears dishevelled and a bit disoriented. (In another journal entry he admits, ‘I stagger about amidst life that is alive’ (Tøjner 2003: 62).) He stands facing us in the doorway of two rooms that define his existence, his studio and his bedroom: where he works unceasingly and where he sleeps—or tries to sleep, since he suffered from severe insomnia.

Munch’s long gaunt body echoes the tall—faceless—clock and the bed, a bed in which time stops, where the finality of death is confronted, as Heidegger observed in Being and Time in 1927 (1962: 239). This is a painting about the disappearance of time, the imminence of death, and fear of The End. While time might stop for the clock, faceless as it is, the clock that ticks in Munch’s body doesn’t. (He died only a few months after he finished this painting.)

Death, what awaits us ‘on the other side’, and what we leave behind for others to pick through, destroy, or ignore, co-exist in this painting. The fear of death confronts us all, and it is thus also the fear of an artist. For Munch, who never married and had no children, painting was the shape of his life—how he kept time, marked time, and how he experienced the past and the future. His paintings are his progeny. They are the tangible, material, aesthetic evidence of his presence, his life, and its significance. What will become of them? How will they live on? Will they live on? And will anyone care?

Munch’s tired posture displays the fatigue of a long, difficult, and pain-filled personal history, but he remains alert, on guard. He still looks intensely at, and for, life.

References

Heidegger, Martin. 1962. Being and Time, trans. by John Macquarrie and Edward Schouten Robinson (London: SCM Press)

Tøjner, Poul Erik. 2003. Munch: In His Own Words (Munich: Prestel)

Paul Klee

Angelus Novus, 1920, Oil transfer and watercolour on paper, 318 x 242 mm, The Israel Museum, Jerusalem; Gift of Fania and Gershom Scholem, Jerusalem; John Herring, Marlene and Paul Herring, Jo Carole and Ronald Lauder, New York, B87.0994, The Israel Museum, Jerusalem, Israel / Carole and Ronald Lauder, New York / Bridgeman Images

An Angel’s Hinterland

Commentary by Daniel Siedell

The day of the Lord will come just like a thief in the night.

(1 Thessalonians 5:2 NASB)

Swiss-born artist Paul Klee (1879–1940) painted hundreds of angels throughout his career. Their simplicity and directness; playfulness and seriousness; bringing of blessings and curses, comfort and judgement, redemption and damnation, were conjured from an imagination eager to create a sovereign transcendent ‘beyond’ whence these messengers were sent for his and our benefit.

But what makes this little angel, Angelus Novus, so extraordinary that it should have become an icon of the twentieth century? It has to do with the person for whom it suddenly appeared, seizing his attention at an art gallery in Munich in 1921 and becoming his companion, inspiration, and comfort for nearly twenty years.

This person is Walter Benjamin, one of the great cultural critics of the twentieth century. And Klee’s little angel served as an inspiration for numerous essays on modern art and culture.

‘There is a painting by Klee called Angelus Novus’.

So begins the most famous passage in his essay, ‘Theses on the Philosophy of History’, written shortly before he committed suicide to avoid arrest by the Nazis in 1940. This ‘Angel of history’, with his face ‘turned toward the past … sees one single catastrophe…’

On view at the Jerusalem Museum, Angelus Novus is an artistic memorial to the suffering and violence of the twentieth century and the arrogance of modernity. But it also bears witness to the important role that art and literature played in addressing such suffering, violence, and arrogance, whose voice comes from somewhere where existence is not reduced to suffering, violence, and arrogance. Angelus Novus did not come into the world merely to condemn. From this ‘somewhere’, the painting offers the potential, if ever so slight and faint, of freedom, redemption. In this way it is an icon of hope. A painting for the faithful. Not unlike Paul’s letter.

References

Benjamin, Walter. 1968. ‘Theses on the Philosophy of History’, in Illuminations, ed. by Hannah Arendt, trans. by Harry Zohn (New York: Schocken Books), pp. 253–64

Hilma Af Klint

Altarpiece No. 1, Group X, 1915, Oil and metal leaf on canvas, 237.5 x 179.5 cm, Klint Foundation, Stockholm; HAK187, Private Collection / Bridgeman Images

Behold, I Tell You a Secret

Commentary by Daniel Siedell

‘For God has not destined us for wrath, but for obtaining salvation…’ (1 Thessalonians 5:9 NASB)

Hilma af Klint’s (1862–1944) painting is an imposing and overwhelming canvas, to say the least. It stands over nine feet tall and seven feet wide, consisting of circular and triangular forms made of grids and spheres of bright colour on a black ground, a colossal painted mosaic that represents nothing, and yet seems to possess the secret meaning of Everything. The cosmic, universal connotations of a transcendent origin—and a future destiny—are not directly represented or expressed in the content of the painting, but they are at work in this and hundreds of other similar canvases that Klint called ‘Temple’ and ‘Altarpiece’ paintings.

How does an artist like Klint, who enjoyed a modestly successful career as a portrait and naturalistic landscape painter after formal training at the art academy in Stockholm, come to paint such immodest paintings? And why? Their appearance in the world undermines everything we’re taught to believe about the history of art, which is a map of stylistic influences, of causes and effects that develop organically, gradually.

Klint renders this model useless as a means to interpret these mysterious paintings, which were painted nearly a decade before the art historical ‘birth’ of abstraction. How can that be?

Rather than a product of ‘art history’ per se, they are the result of Klint’s study of spiritualism, including her regular attendance at séances where she communicated with spirit guides, through which she recorded her philosophical insights into the universe. The result was thousands of pages of writings and over a thousand paintings.

Klint also refused to exhibit them in her lifetime, stipulating in her will that they could only be shown twenty years after her death (she died in 1944). Klint believed that she had learned secrets of the universe. Why the secrecy? Why wait to share them? Is it possible that these remarkable—even miraculously conceived—paintings were destined for an audience that would only be ready to receive them at a later moment? Perhaps Klint’s viewers of the future can be compared with the first departed Christians in Thessalonica, who would only come to a full appreciation of their ultimate destiny after waking from ‘sleep’ (1 Thessalonians 4:13–17).

Edvard Munch :

Self-Portrait between the Clock and the Bed, 1940–43 , Oil on canvas

Paul Klee :

Angelus Novus, 1920 , Oil transfer and watercolour on paper

Hilma Af Klint :

Altarpiece No. 1, Group X, 1915 , Oil and metal leaf on canvas

The Day of the Lord

Comparative commentary by Daniel Siedell

Put on the breastplate of faith and love, and as a helmet, the hope of salvation. (1 Thessalonians 5:8 NASB)

How long will we have to wait, to struggle, to suffer in this broken world? How long will we have to wait before it is healed, before we’re healed? This is what the religious community in Thessalonica wanted to know from the apostle Paul. They had been taught that Jesus would come again, soon. But he had yet to come. And what will happen when (and if) he comes? How will we know? What do we do in the meantime?

After the devastation of the First World War, and the catastrophic loss of life as well as the economic, political, and cultural crises that ensued (including, eventually, further violence and death in the Shoah), many artists and writers returned to the apocalyptic and messianic texts of the Old and New Testaments in search of something that saturates the biblical literature: hope for redemption. In 1951, the philosopher Theodor W. Adorno even wrote that philosophy must now be practised ‘from the standpoint of redemption’ (2005: 247).

It is out of this cultural crisis and search for redemption that the works by Paul Klee, Hilma af Klint, and Edvard Munch emerge. What they can remind readers of 1 Thessalonians is that Paul is stressing a daily life lived in the present in light of future redemption, through hope. Far from being merely a disposition toward the future, hope in this text is a lived practice in the present, underscoring and enlivening even our most mundane and seemingly irrelevant daily tasks, even the making of paintings.

Hope is not merely something that is future-oriented; it is what motivates and sustains the present, underwriting the courage and perseverance to live each day in its light. While Adorno’s ‘redemption’ may envisage a purely human event, its arising from creative human agency might nevertheless be something miraculous.

Hope may perhaps be compared with that to which Paul refers elsewhere as the ‘today’ of salvation (2 Corinthians 6:20). It is Klint living day to day with her ‘secret’ knowledge and experience of the cosmos that inspires and sustains her daily work as a writer and painter as she works on behalf of future audiences. To stand before one of these paintings is to realize that we are the intended audience for her work, that it is her hope that sustains us, as she shares her vision of a future destiny.

Klee’s awkward and vulnerable little Angelus Novus made a powerful impression on Walter Benjamin’s understanding of history and the future. He called it ‘the Angel of History’ and described it as a ‘flash’ that occurs at a ‘moment of danger’ (1968: 255, 257). Benjamin and Klee thus remind the reader of 1 Thessalonians 5 that the Lord often makes appearances in unremarkable and even unnoticed ways, whether in a still small voice (1 Kings 19:11–13), mistakable for a gardener (John 20:15), or a fellow traveller (Luke 24:15ff). In other words can we ever be certain that the day of the Lord, the return of the Messiah, those transformative miraculous moments, haven’t already come? While in our zeal for pomp and circumstance we have missed them, failing to be aware and sober, ever alert for this appearance?

Walter Benjamin writes that although the Jews ‘were prohibited from investigating the future’, time was imbued with a fullness of expectation, a fullness wrought by hope. ‘For every second of time was the strait gate through which the Messiah might enter’ (1968: 264). Redemption, miraculous moments, can and do occur daily, while we are going about our daily work. Putting on faith, hope, and love as our armour for daily battle opens us up to the ‘day of the Lord’ at any moment. In fact, it includes us in the work of such coming. As God comes, redemption occurs through faithful human agency, generated from hope and for love—love of our neighbour. For Benjamin, Angelus Novus became one of those ‘strait gates’, a secular ‘day of the Lord’.

And finally, we are confronted by a tired, frail, and dying Edvard Munch, dealing moment-by-moment with the fear and anxiety of his death, confronting his vulnerability and fragility, yet continuing to work, painting pictures. Like Munch, we’re left with our worn-out bodies, fearful minds, and a room full of our work, of whose ultimate value we have no idea. And yet, as Paul counsels, we continue to labour daily, even if that labour is to paint pictures, and do so armed with faith, hope, and love, and a confidence that there was, is, and will be redemption.

And these paintings, in their own very different ways and from their own very different circumstances, say ‘amen’.

References

Adorno, Theodor W. 2005. Minima Moralia: Reflections on a Damaged Life (London: Verso)

Benjamin, Walter. 1968. ‘Theses on the Philosophy of History’, in Illuminations: Essays and Reflections, ed. by Hannah Arendt, trans. by Harry Zohn (New York: Schocken Books), pp. 253–264

Commentaries by Daniel Siedell