Genesis 8:20–9:17

The First Rainbow

Unknown artist

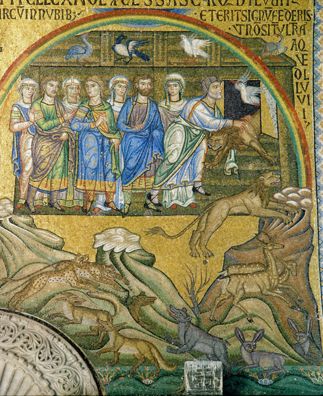

The Rainbow and Noah Freeing the Animals from the Ark, from the south barrel vault, west narthex, 13th century, Mosaic, Basilica di San Marco, Venice; Heritage Image Partnership Ltd / Alamy Stock Photo

Après le Déluge

Commentary by Stefania Gerevini

This mosaic belongs to a lengthy Old Testament cycle in the atrium of the church of San Marco, Venice, from the thirteenth century. The scene conflates Genesis 8:18–19 with Genesis 9:11–17, providing a vivid visual rendition of the covenant sealed by God with humankind at the end of the deluge.

In this mosaic, which is accompanied by several other episodes from the story of the deluge, Noah has finally left the ark together with his wife, his three sons, and their wives (Genesis 8:18), the forebears of all earthly nations. These figures are framed by a rainbow, at once created by God as the tangible token and perennial reminder of his promise that never again ‘will the waters become a flood to destroy all life’ (Genesis 9:15).

As a narrative of rescue from death by drowning, the biblical deluge is likely to have held intense appeal in Venice. The city was built on water: it was vulnerable to floods and high tides, and its prosperity depended then—as it does now—on a fragile ecosystem. In addition, Venice’s economy relied on shipbuilding and maritime trade, making its citizens especially sensitive to atmospheric phenomena, and to the dangers of storms. These first-hand experiences surely tinted Venetian receptions of the biblical deluge. In turn, familiarity with the biblical text may have amplified the local significance of the rainbow as a token of hope, and as assurance of God’s benevolence towards the water-bound community.

Confirming such topical inflections, Noah is represented in the act of freeing animals to re-populate the earth (Genesis 8:19). While several species roam freely in the lower portion of the scene, the iconographic focus is on a pair of lions. Their prominence is probably not accidental. The lion was the symbol of Saint Mark and of the city of Venice. Its presence in the mosaic implied Venice’s membership in the biblical covenant. It reassured viewers of God’s continuing good will towards the city. And it demonstrates to us how medieval communities engaged with sacred history, and made it relevant to their present concerns.

References

Demus, Otto. 1984. The Mosaics of San Marco in Venice, 2 vols (Chicago: University of Chicago Press)

Vincenzo Foppa (?)

Dome, c.1462–68, Fresco, Portinari Chapel, Basilica of Sant'Eustorgio, Milan; akg-images / Mondadori Portfolio / Mauro Ranzani

‘Like a Rainbow’

Commentary by Stefania Gerevini

The Cappella Portinari was erected in the mid-fifteenth century at the north-east of the Dominican church of Sant’Eustorgio in Milan. Commissioned by the wealthy banker Pigello Portinari, it became the patron’s funerary chapel at his death in 1468. Upon entering the chapel, the viewer is enraptured by the expanse of its dome, richly ornamented with four bands of colour, arranged concentrically around the lantern at the summit.

This painterly decoration invites discussion in relation to contemporaneous understandings of the rainbow in natural philosophy and theology. By the fourteenth century, experts on perspective and meteorology tended to agree that the rainbow comprised four colours: red, yellow, green, and purple or blue, arranged in this order. The dome of the Portinari Chapel features these colours, disposed precisely in this sequence, indicating that its decorative program was indeed intended to be understood as a rainbow.

Based on Genesis 9:12–13, medieval theologians conceived of the rainbow as an intermediary between heaven and earth, and as a reminder of God’s benevolence towards his creation. This connotation was both sustained and complicated by the book of Ezekiel (1:28) and Revelation (4:3), where the image of the rainbow expresses the radiance of God’s glory. While the Genesis passage unambiguously identifies the arcus in the sky as a token of covenant and protection, Ezekiel’s and John’s visions are more ambivalent. The rainbow still manifests divine presence, but its appearance—which eminent medieval theologians, including Isidore of Seville (De Natura Rerum) and Hrabanus Maurus (De Universo), interpreted as evocative of the Last Judgement—is more fearsome than reassuring.

In its dual meaning as token of divine benevolence and reminder of the judgement that awaits all souls, the iridescent cupola of the Cappella Portinari infuses the space with explicit eschatological connotations. These were consistent with the original function of the chapel as a funerary shrine, and also offered a flexible canvas for the theological and scientific reasoning of the Dominican friars of Sant’Eustorgio.

References

Gitlin Bernstein, JoAnne. 1981. ‘Science and Eschatology in the Portinari Chapel’, Arte Lombarda, 60: 33–40

Dan Flavin

Untitled, 1996, Green, ultraviolet, blue, pink, and yellow fluorescent light, Nave: two sections, each 28 m wide; Transept: two sections, each 9.75 m wide; Apse: two sections, each 9.75 m high, Permanent installation at Santa Maria Annunciata in Chiesa Rossa, Milan; Copyright: © 2020 Stephen Flavin / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York; Image: Courtesy David Zwirner

‘Presiding Presence’

Commentary by Stefania Gerevini

Dan Flavin's light installation at Santa Maria Annunciata in Chiesa Rossa in Milan was the last project designed by the artist before he passed away in 1996, making this artwork his ‘aesthetic testament’.

Upon entering the church—which still functions as a place of worship—the beholder is confronted with two parallel lines of ultraviolet light, spanning the length of the nave. Positioned at the intersection between colonnade and barrel vault, these lights emphasize the longitudinal axis of the building, directing the viewer’s gaze towards the apse. The ultraviolet tubes also fill the nave with a deep blue tint, which stands in sharp visual contrast with the intense reddish-pink hue of the transept and the golden yellow that colours the apse. The overall visual effect is that of an architectural space made of light, rather than simply illuminated by it.

Flavin vocally rejected any symbolic or metaphysical interpretations of his works. Yet, in the early Sixties, he entitled his first series of light-works ‘Icons’ in homage to Orthodox religious paintings, whose ‘presiding presence’ (as he wrote in a record book in 1962—see Ragheb 1999: 62) he tried to realize in his own works.

Flavin’s notion of ‘presiding presence’ may offer a useful interpretative cue to his multicolour installation in Milan. The choice and juxtaposition of colours—blue, pink/red, and yellow—in the Chiesa Rossa is evocative of the biblical rainbow. In the Genesis narrative, the rainbow is not summoned as a mere metaphor of God’s covenant with creation. Instead, it establishes the new alliance, and is effective against divine ire every time it appears in the sky.

Similarly, in Ezekiel and Revelation, the rainbow does not represent a symbol, but is, rather, an intrinsic part of the theophany by which divine presence and radiance are manifested.

Flavin’s installation operates in a similar fashion. It transports the faithful into an ethereal, tinted atmosphere, which glows like a jewel and tinges their skin in blue, red, and yellow as they move across the church. In doing so, this light-work manifests divine radiance, and marshals the rich semantics of the rainbow in Christian scriptural tradition and aesthetics to instantiate God's presence and its transformative power in relation to the human soul.

References

Celant, Germano, and Dan Flavin. 1997. Santa Maria in Chiesa Rossa, and Fondazione Prada. Cattedrali d’arte: Dan Flavin per Santa Maria in Chiesa Rossa (Milan: Fondazione Prada)

Ragheb, Fiona J. 1999. Dan Flavin: The Architecture of Light (Berlin: Deutsche Guggenheim)

Unknown artist :

The Rainbow and Noah Freeing the Animals from the Ark, from the south barrel vault, west narthex, 13th century , Mosaic

Vincenzo Foppa (?) :

Dome, c.1462–68 , Fresco

Dan Flavin :

Untitled, 1996 , Green, ultraviolet, blue, pink, and yellow fluorescent light

Bands of Light and Bonds of Love

Comparative commentary by Stefania Gerevini

Over just a few lines, Genesis 9:11–17 reiterates four times the significance of the rainbow as signum foederis—the sign, or visible token, of the covenant between God and creation, and the reminder of His promise never again to destroy the earth by a flood. This is an image of extraordinary potency and delicacy. The rainbow is the most evanescent of atmospheric phenomena. Yet, of all things, God chose this diaphanous entity as the antidote against His wrath.

How do the artworks brought together in this exhibition relay the role of the rainbow as intermediary? How do they visualize the biblical image of an impalpable thing of light that protects the world from destruction?

The mosaic of San Marco is the most literal of the three renditions. Here, the apex of the rainbow touches a blue hemicycle that stands for the sky, while its end touches the ground near the lion of Venice, visually bridging earth and heaven.

In the Cappella Portinari the significance of the rainbow as intermediary between God and creation is expressed through sophisticated interactions between natural light, architecture, and painting. Sunlight—an enduring symbol of the divine—filters into the chapel through the lantern at the summit of the dome. The concentric bands of colour in the cupola, arranged around the lantern, visually manifest the divine origin of the rainbow. Hovering majestically above the beholder, the rainbow dome simultaneously conjures the biblical covenant and the radiance of God at the end of time. Thus, it encourages viewers to weave together Genesis and Revelation, and to reflect upon the reciprocity between divine power and mercy.

Finally, Dan Flavin’s installation immerses the faithful in densely coloured air—making them experience the transformative power of divine presence.

These artworks craftily exploit physical light, and its interaction with different artistic media and with architecture, to render the ephemeral and visually unstable nature of the rainbow. Mosaic is a highly reflective medium. It glitters when hit by light-rays, but becomes dim and lustreless in low lighting. Just as the rainbow appears in the sky when light pierces the clouds at their darkest, so the light of candles or sun beams brings the dazzling gold background of the mosaic of San Marco to life, and enlivens the image of the arc in it. The Cappella Portinari also significantly interacts with light. The fish-scale design of its dome diffuses natural light, creating a palpitating, misty visual effect that conjures the impalpability of the rainbow. Even more radically, Flavin’s installation changes with the seasonal cycle and according to the time of day. Barely perceptible in daylight, it becomes progressively more intense and saturated as natural light decreases. At nightfall, or on gloomy days, the church literally glows, almost a rainbow against dark skies.

While each of these artworks visually relates to the rainbow, and to the biblical passage that records its first appearance, they also work on other planes of meaning. Appropriately for the state church of Venice, the mosaic in the atrium of San Marco transforms the biblical episode into an implicit assertion of Venice’s myth of predestination: the idea that the city was especially favoured by God. The Cappella Portinari, built for a community of learned Dominicans, favoured an abstract ‘colour field’ over figural representations of the Scriptures. This visual device enabled the friars to exercise their theological knowledge, linking the narrative of divine goodwill and protection presented in Genesis with notions of divine judgement and ideas of beatific vision from Ezekiel and Revelation. Finally, Flavin’s work was installed in the parish church of a less affluent urban neighbourhood, and was intended for a mixed audience of clergy and laypeople. This installation is the most elusive of the three artworks. It offers a spectacular and overpowering manifestation of divine presence. Yet, it eschews univocal interpretation or direct associations with a scriptural passage. Instead, it alludes to a range of theological concepts that lie at the core of the Christian faith: the relationship between God and humankind, and between eternity and temporality; the proceedings of divine grace; and the connection between the Old Testament covenant mediated by the rainbow, and the new covenant mediated by Christ.

Together, these artworks manifest the fruitfulness and complexity that mark all interactions between the Scripture and the images that seek to relay its meaning. On the one hand, even the most literal visual rendition of the bible entails high degrees of interpretative freedom, inevitably transforming the text through specific aesthetic, social, and cultural lenses. On the other hand, the visual—enigmatic and open-ended by nature—is uniquely capable of manifesting the vinculum between what is visible and what cannot be seen, thus entering a fruitful dialogue with Scripture, and sharing in its revelatory power.

Commentaries by Stefania Gerevini