2 Corinthians 3:12–4:18

From Glory to Glory Advancing

Works of art by Albrecht Dürer, Francisco de Zurbarán and Unknown Mughal artists from Gujarat

Albrecht Dürer

Self Portrait in a Fur-Trimmed Robe, 1500, Oil on panel, 67.1 x 48.9 cm; 537, bpk Bildagentur / Alte Pinakothek, Bayerische, Staatsgemaeldesammlungen, Munich, Germany / Art Resource, NY

Paradox in Portraiture

Commentary by Ursula Weekes

Paul writes of ‘the light of the knowledge of the glory of God in the face of Christ’ (2 Corinthians 4:6). How might divine glory be seen in a human face?

Albrecht Dürer’s portrait of himself aged 28 is one of the masterpieces of German Renaissance art. The power of the portrait is built on a paradox of identity. The frontal pose and the compositional structure of the face and hair is predicated on a long history of images of iconic, ‘true’ portraits of Jesus, deriving from miracle narratives such as the St Veronica legend and the Mandylion of Edessa. The face, from the top of the head to the v-point of the robe at the base of the neck, is governed by a perfect equilateral triangle, circle, and square, superimposed on each other, with their central intersecting lines crossing just beneath the nose. The application of sacred geometry to the construction of the face, connects it with divine beauty.

But the portrait is unmistakably of Dürer, not Jesus. The paradox of the figure’s identity is further heightened by a moral paradox: the portrait is both glorious and vainglorious. Dürer’s virtuoso talent as a painter is unashamedly celebrated. His curly hair is lavishly depicted. His right hand pinches the expensive fur trim of his robe to remind us of his professional success. Dürer omits his left hand at the bottom edge of the panel as a subtle reminder that his painting hand was not at rest in making the image. On the left, the date 1500 is emblazoned with the monogram ‘AD’, referring not only to ‘Albrecht Dürer’ but also to ‘Anno Domini,’ the ‘year of the Lord’. On the right, the Latin inscription states how the artist has portrayed himself with ‘indelible colours’. Dürer clearly desired immortality as a painter.

Dürer’s self-promotion may not make him the best exponent of Paul’s claim ‘what we preach is not ourselves’ (4:5). But might he also illustrate—if only in parody—the powerful attraction of Christian transformation, ‘being changed into his likeness from one degree of glory to another’ (3:18)?

References

Koerner, Joseph Leo. 1993. The Moment of Self-Portraiture in German Renaissance Art (Chicago: University of Chicago Press)

Francisco de Zurbarán

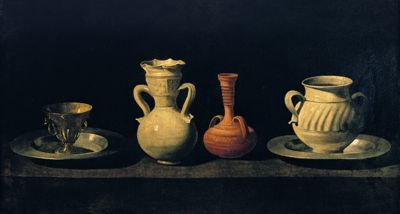

Still Life with Vessels , c.1650, Oil on canvas, 46 x 84 cm, Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid; Bequest of Francisco de Asís Cambó, 1940, P002803, Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid, Spain / Bridgeman Images

Treasure in Earthen Vessels

Commentary by Ursula Weekes

Paul’s life was full of affliction, perplexity, and persecution, but through these trials he was able to say that he was not crushed, not driven to despair, not forsaken, and not destroyed (2 Corinthians 4:8–9). He knew that in Jesus, he had treasure of unsurpassing worth, and that his body was like an earthen vessel (4:7) displaying the extraordinary power of eternal life in the face of death (4:11–12).

This seventeenth-century Spanish Still Life with Vessels by Francisco de Zurbarán has a wonderful asceticism, not so much in the objects themselves, but in the way they are arranged with ordered simplicity. Zurbarán spent much of his career in Seville painting monastic figures and saints, and this painting with its strong chiaroscuro lighting imbues the vessels lined up on a shelf with a spiritual atmosphere. We contemplate them intimately, close to the picture plane, with a dark background that does not allow for any recession.

There is a silver gilt goblet with little dragon handles, standing on a pewter plate at the left. Next to it is a water jug, and on the far right a white vase, both of which are from Triana in Seville, and made of a type of porous earthenware that cools water through evaporation, known as eggshell. In between these, is a terracotta vase from the Indies, at that time part of the Viceroyalty of New Spain.

There are many aspects of the painting that do not conform strictly to the rules of perspective and the fall of light. Most prominent is the fact that the tall Triana water jug does not cast a full shadow onto the terracotta vase to its right, and different vessels are seen from slightly different vantage points in relation to the shelf.

Paul in 2 Corinthians visualizes jars of clay, and imagines them filled with treasure (4:7). Zurbarán seems to treasure the possibilities in the earthly vessels that are his subject. And, maximizing the play of light on their surfaces in order to emphasize their volumes, he like Paul makes us think about the possibilities of what they contain.

References

Delenda, Odile, and María del Mar Borobia Guerrero et al. 2015. Zurbarán: A New Perspective (Madrid: Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza)

Unknown Mughal artists from Gujarat

Jali Lattice Window, c.1572, White marble, 3m x 1.5m (approx.), Humayun’s Tomb, Delhi; Pocholo Calapre / Alamy Stock Photo

Beyond the Veil

Commentary by Ursula Weekes

How can we behold God, seeing beyond the temporary to what is eternal?

Paul addresses this question in 2 Corinthians 3–4 as he describes what it means to be a minister of the new covenant in the Spirit (3:6), contrasted with the ‘ministry of condemnation’ in the old covenant (3:8). Paul’s answer traces the unveiling of God’s identity from the first act of his speaking light into creation, through the pivotal moment of revelation in the face of Christ (4:6), to the future eternal glory of heaven (4:17). The idea of a veil is used throughout the passage, first to explain the impermanent glory of the dispensation under Moses (3:13), and then as a metaphor for the spiritual blindness that can only be removed in Christ (3:16).

This intricate lattice screen is an exquisite example of jali (pierced stonework) from Mughal India. It is part of the tomb of the Emperor Humayun, constructed in Delhi between 1565 and 1572. The tomb was commissioned by his son Akbar and was an important architectural precursor of the Taj Mahal. The jali is made of white marble, which was a material closely associated with the purity of divine light in Mughal architecture. Its complex geometry was considered sacred in Islamic art, revealing the underlying mathematical order of creation and thus leading one to the mind of God.

The jali lattice obscures the view outwards. At the same time, it allows the inward flow of sunlight in scattered geometric shapes as though revealing a heavenly light from God. It’s like a veil that defines a boundary between the material world of appearances and the eternal reality of God’s presence. The screen is something concretely visible, but at the same time it ‘dissolves’ itself, enabling us to discern something beyond it; to perceive the creator God ‘who said let light shine…’

Paul sees a similar dynamic in the way the earlier dispensation, represented by Moses, exists to open a way beyond itself, but also in the way Paul himself fulfils his calling by ‘unselving’ himself so that the greater light of Christ can shine through (4:15).

References

Asher, Catherine Ella Blanshard. 2008. Architecture of Mughal India, The New Cambridge History of India, 4 vols (Cambridge University Press)

Albrecht Dürer :

Self Portrait in a Fur-Trimmed Robe, 1500 , Oil on panel

Francisco de Zurbarán :

Still Life with Vessels , c.1650 , Oil on canvas

Unknown Mughal artists from Gujarat :

Jali Lattice Window, c.1572 , White marble

Knowing Where to Look

Comparative commentary by Ursula Weekes

These two chapters of 2 Corinthians are saturated with the language of gazing, beholding, looking, shining, and glory, oriented around two contrasting concepts: the veil and the face.

For Paul, the old covenant under Moses was a partial revelation of God’s glory, a ‘dispensation of condemnation’ (2 Corinthians 3:9), because the Law was powerless to save. It revealed sin and showed the need for a Saviour. Under this dispensation, only a few people, like Moses, were intimate with God. Moses had a shining face after speaking to God on Mount Sinai, but he had to cover it with a veil in front of the Israelites because they did not have the same access to God (3:13). The veil thus symbolizes spiritual blindness (3:14). But under the new covenant, when someone turns to the Lord, ‘the veil is removed’ (3:16), giving all people the opportunity to know God personally through Jesus.

The pierced lattice window of Humayun’s tomb is a veiling that becomes the occasion of an unveiling; an enclosure that leads to disclosure. It creates an interface between the dark interior of the tomb and the bright Indian sunlight that pours through its intricately cut shapes, shapes which intimate divine perfection. Like a veil that undoes itself, the jali is a signpost towards the God the creator.

It is, then, far from being a static work of art, and its constant interaction with the shifting sun may also signify something of the God who, as Paul insists, is dynamic and personal in time. He ‘has made his light shine in our hearts’ (4:6). He knows who we are, and understands the complex shifting patterns of our lives.

Paul visualizes the new covenant with the concept of the face. The glory of God (echoing the Hebrew shekinah: God’s saving presence) is revealed in the face of Christ: ‘For God, who said ‘let light shine out of darkness’, has shone in our hearts to give us the light of the knowledge of the glory of God in the face of Christ’ (4:6).

Albrecht Dürer’s self-portrait is all about the face as a divine construction. Dürer’s identity and that of Christ are inextricably bound as he superimposes the likeness of Christ onto his own appearance. Scholars have long argued over Dürer’s intentions here. His career shows he had a deep interest in his own status and so he was probably highlighting his god-like creative ability. But, paradoxically, this work can nevertheless illuminate a Pauline point. Sinful human beings can, by grace, experience God’s transforming power in their lives to become more like Christ, for ‘we all with unveiled face, beholding the glory of the Lord, are being changed into his likeness from one degree of glory to another’ (3:18). Even Paul might have enjoyed this twist, for (as chapter 4 shows) he was a lover of paradoxes: light shining out of darkness; treasure found in clay pots; bodies dying in order to witness to life. Pride here is an inadvertent witness to grace.

Knowing ‘the glory of God in the face of Christ’ is a ‘treasure’ to Paul, but he stresses that there is no place for self-righteousness, for ‘we have this treasure in earthen vessels, to show that the transcendent power belongs to God and not to us’ (4:7). In Francisco de Zurbarán’s Still Life with Vessels, the two white water jugs in particular are everyday earthenware objects, no doubt often broken and chipped in Spanish homes. Meanwhile, the goblet and vase at the outer edges stand on pewter plates. They are like everyday versions of eucharistic vessels—and we find eucharistic associations too in Paul’s description of his life in 4:11–15. Although he is ‘always being given up to death for Jesus' sake’, his description culminates in the idea of ‘thanksgiving’ (the Greek word eucharistia means ‘thanksgiving’) ‘for it is all for your sake, so that as grace extends to more and more people it may increase thanksgiving, to the glory of God’ (4:15).

Christians are jars of clay, breakable and weak; they face affliction and suffer. But afflictions, too, are like a kind of veil that the believer must look through to an eternal glory beyond, which brings us back to the dissolving lattice jali at Humayun’s tomb. It articulates an intersecting point between the visible and invisible. As Paul concludes, ‘we look not to the things that are seen but to the things unseen; for the things that are seen are transient, but the things that are unseen are eternal’ (4:18).

Commentaries by Ursula Weekes