Genesis 1:3–5

Let There be Light

John Martin

The Creation, from Illustrations of the Bible series, 1831, Mezzotint in black on ivory wove paper, 329 x 416 mm, The Art Institute of Chicago; Album / Alamy Stock Photo

Dawn of Creation

Commentary by Naomi Billingsley

The first in a series of biblical illustrations by John Martin, this print presents us with the dawn of creation. The artist adapted the design from a similar composition in his illustrations to John Milton’s Paradise Lost (1825). Milton’s poem (1667) contains a narrative of Creation in six days that follows the account in Genesis.

In his earlier design, Martin had focused on the deity placing the lights in the heavens on the fourth day (Book 7, Line 339)—the sun, the moon, and the stars. In this later image, the inscription cites Genesis 1:2–3 and so refers to the creation of light itself on the first day. Nevertheless, the work encapsulates all of the first four days of Creation: light, firmament, dry land, and lights in the heavens are depicted together here. Martin may simply have wanted to depict several aspects of God’s work of Creation, but his decision to depict several episodes simultaneously might also reflect the difficulty of depicting the first appearance of light as a stand-alone subject.

As in his Paradise Lost design, Martin depicts the deity placing the sun in the sky. However, here, the figure is less distinct. Martin was probably responding to contemporary critics who were outraged by the prominent figure of the deity in the earlier design.

The sun and moon are also more diffuse in this later image, perhaps in recognition of the fact that their creation is not properly accomplished until the fourth day. The light does not all emanate from the sun, as we would normally expect. As a contemporary critic noted, we also seem to see ‘light, for the first time, … shed[ding] its genial influence on the cold dark matter of the chaotic world’ (Anon. 1831: 253) prior to the heavenly bodies becoming light’s specific source.

Martin has depicted the world before living things. It is light alone that has vitality in this opening scene of his series.

References

Anon. 1831. ‘New Publications’, The Athenaeum, 181

John Piper and Nicholas Patrick Reyntiens

Baptistry window in Coventry Cathedral, 1957–61, Stained glass, Coventry Cathedral, Warwickshire; Monica Wells / Alamy Stock Photo

Light above Water

Commentary by Naomi Billingsley

On 14 November 1940, Coventry Cathedral was destroyed in one of the most devastating bombing raids of the Second World War.

A new cathedral was built adjacent to the ruins of the old church between 1956 and 1962. From the earliest stages of the project the architect, Basil Spence, worked collaboratively with other artists. Spence commissioned John Piper to design the windows of the Baptistery, which Piper realized in partnership with glassmaker Patrick Reyntiens.

The curved window contains 198 lights that, together with the stonework, form a grid. The coloured glass is schematically arranged so as to emit a large blaze of light when illuminated, with lights of green, red, and blue surrounding the yellow lights at the centre of the window.

Piper stated that the blaze of light symbolizes the Holy Spirit. The Spirit of God hovered over the face of the water at Creation, just as it descended upon Jesus at his baptism in the Jordan. Here, it is evoked in the light of the window above the cathedral’s place of baptism—a powerful backdrop for the performance of the sacrament.

The blast of light of the window can also be seen as representing the light of Christianity, or the original light of Creation. We can imagine not just the Spirit hovering over the waters, but also the light that God first summoned into being.

There is a long tradition of association between baptism and Creation. In baptism, an individual becomes a member of the church community, and so baptism is itself a moment of new creation. It is a death followed by a rebirth; a transfer from the power of darkness to the power of light. The Baptistery window speaks to the new creation of the individuals who are baptized before it, and of Coventry Cathedral’s rebirth after the war.

As Frances Spalding has noted, when the light is right, the colours of the window are cast on to the Baptistery, making that light a participant in the liturgy of rebirth and recreation that takes place there (2009: 379).

References

Spalding, Frances. 2009. John Piper. Myfanwy Piper. Lives in Art (Oxford: Oxford University Press)

Paul Nash

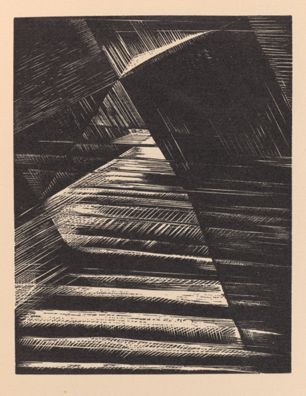

The Division of the Light from the Darkness, Illustration III, in the book Genesis from the Bible (Soho, London: The Nonesuch Press), 1924, Wood engraving on Zanders hand-made laid paper, Image: 113 x 87 mm, Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco; Reva and David Logan Collection of Illustrated Books, Gift of John Flather and Jacqueline Roose, 2001.45.1.3, Image courtesy the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco

Light in Chaos

Commentary by Naomi Billingsley

What might light without a source look like? That scientific impossibility is the subject of this woodcut by Paul Nash.

The print is the third in a series of twelve designs by Nash relating to the Creation narrative in Genesis 1. Each image is accompanied by the text of the relevant verse(s) of Scripture, and has a title based on the subject. The Division of Light from Darkness is accompanied by the three verses that are explored here (1:3–5).

The work depicts multiple shafts of light emerging from the darkness. The division is marked in the delineation between very dark portions of the image to the right and top left, and sections that are dominated by shafts of light to the left and at top centre.

The roughly horizontal beams of light that predominate at the lower left echo the ripples in the waters in the preceding plate, The Face of the Waters (Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, 2001.45.1.2). The suggestion, perhaps, is that these shafts of light are travelling across the surface of the water.

But other rays of light travel upwards, seeming to emerge from the upward-facing surface of the dark, angular form at the upper right of the image. This dark shape also seems to reflect some of the horizontal lines, perhaps suggesting that it is another mass of water.

Throughout the composition, the light beams vary in length, intensity and direction. There is no single point of origin for the rays of light, nor a pattern to how they behave. This chaos reflects the fact that the ‘lights in the firmament’ (KJV)—the sun, moon and stars—are not created until verse 15, so the light seen here is without physical source.

This inaugural moment of Creation manifests God’s unbounded creativity, which is not limited by the world’s laws of causation. The strangeness of the play of light in Nash’s design encourages us to reflect on the Creation account in Genesis 1 as an expression of the seemingly impossible becoming the very foundation of reality.

John Martin :

The Creation, from Illustrations of the Bible series, 1831 , Mezzotint in black on ivory wove paper

John Piper and Nicholas Patrick Reyntiens :

Baptistry window in Coventry Cathedral, 1957–61 , Stained glass

Paul Nash :

The Division of the Light from the Darkness, Illustration III, in the book Genesis from the Bible (Soho, London: The Nonesuch Press), 1924 , Wood engraving on Zanders hand-made laid paper

Creating with Light

Comparative commentary by Naomi Billingsley

Light is the first thing that God creates in Genesis 1. It exists even before the sun, moon and stars. Light without a source is a challenging concept to grasp, and (even more so) to represent visually.

Paul Nash’s The Division of Light from Darkness tackles this challenge directly by depicting an abstract mass of shafts of light. It is difficult to read the behaviour of the light in Nash’s image—it does not seem to conform to the laws of optics.

John Martin’s The Creation folds the first four days of Creation into a single image, which depicts the creation of light, the sky, land, and sea, and the sun, moon, and stars. Thus, light is cast from the lights of the heavens, but some of the light in the image appears to be without physical source.

John Piper and Patrick Reyntiens’s Baptistery window at Coventry Cathedral is not explicitly a response to the creation of light in Genesis—the blaze of light that it captures and directs into the Cathedral’s interior is intended to represent the Holy Spirit. Nevertheless, in its context in the Baptistery, surrounding the font that holds the waters of baptism, the window speaks typologically to the first light shining above the waters at the beginning of Creation.

Common to all three works is that light is their medium as well as their subject.

Nash’s woodcut carved light from the darkness of a woodblock. The technique involves carving lines into a block of wood to create an image to be printed. These lines become the white areas of the image when the block is printed. The first design in Nash’s series is a completely black print (Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco 2001.45.1.1) representing the earth ‘without form and void’ (Genesis 1:2 KJV). By beginning the series in this way, Nash emphasizes that in the following eleven plates, he has carved light from darkness. In The Division of Light from Darkness, Nash’s technique and subject matter align with each other.

Martin’s work is a mezzotint. The technique involves roughening the entire surface of the printing plate so that it retains ink. If the plate were printed after this first step, it would produce a black rectangle. The image is created by smoothing parts of the plate so that these areas catch less or no ink, and therefore appear as lighter and white parts of the image. Like a woodcut, a mezzotint creates light from darkness.

While the techniques and effects are different, both Martin and Nash were dividing light from darkness in creating their prints and therefore echo God’s first act of Creation.

Piper and Reyntiens created a window in which the central subject of a blaze of light is fully realized by natural light shining through it. The light of creation illuminates this image of itself.

The window’s ‘image’ of light, harnessing actual filtered light, can also be seen in the context of how the design of the new Coventry Cathedral was conceived after the destruction of the old church in the Second World War. Piper had been an official war artist and had sketched the ruin of the old building the day after its destruction. As David Fraser Jenkins notes, in Piper’s painting of the ruined Cathedral, ‘the tracery is outlined sharply against white’, and therefore in making a bright light the focus of his window design, Piper created ‘an extraordinary echo from one of the lowest points of the war’ (2000: 33).

The fact that light is the first act of Creation is what initiates the cycle of day and night that structures the pattern of Creation in six days. But its priority in the sequence of Creation also represents light dawning from darkness as a moment of beginning. Light followed darkness after the war. Piper and Reyntiens made an image of light for a site that had suffered darkness.

Creation begins with a void in darkness (v.2). Light is the first entity to appear, and the first thing that God calls good (v.4). The Creation account in Genesis 1 is not science. Light cannot appear without a source. That it does so here represents God’s supreme creativity in a way that surpasses all laws of immanent causality.

An artist may identify his or her own process as participating in divine creativity. In representing Creation itself, that resonance is particularly profound, because the subject can suggest analogies with the artist’s act of creation. In the three images of light seen here, the correspondence extends to the mediums of the artworks in the ways that they align with their subject. Martin, Nash, and Piper and Reyntiens do not only depict light; they all in different ways create with light, by channelling the rays of sun, or pushing back the darkness of ink. Their images of light mirror the way that light sprang into existence at the dawn of Creation. These artworks do not merely represent but also embody these verses of Scripture.

References

Jenkins, David Fraser. 2000. John Piper: The Forties (London: Philip Wilson)

Commentaries by Naomi Billingsley