Genesis 1:6–23

The Heavens and the Earth

Unknown artist

The Nebra Sky Disk, c.1800–1600 BCE, Bronze and gold, 30 cm diameter; ©️ LDA Sachsen-Anhalt, Juraj Lipták

Beating the Bounds

Commentary by Robert Hawkins

The ‘dome’ or ‘firmament’ described in Genesis 1:6 and 1:14 translates the Hebrew word Rāqīa meaning something hammered or beaten flat: a Phoenician word from the same root means ‘tin dish’ (Von Rad 1961: 53). This fascinated medieval biblical scholars, who wrote long commentaries considering the material qualities of the firmament. Is it metallic, or gaseous? Is it liquid, and if so, how viscous? Or is it a brittle skin, like an eggshell? Do the heavens ‘wear out like a garment’ (Psalm 102:26; Isaiah 51:6), or are they a symbol of all that is solid and reliable (Psalm 119:89)?

The Nebra Sky Disc is the oldest cosmological depiction we know of, older than the Genesis text by perhaps 1000 years. It renders the heavens as a beaten bronze ground studded with gold stars. But the disc offers more than a mere illustration of the sky. It is a functional object: the gold arcs towards its edges correspond to the angles created between summer and winter solstices observed from the Mittelberg hill near Nebra, in Germany, where it was found. So, the disc represents the sky as an orderly space, as well as a beautiful one. The universe contains signs and marks that can be read and interpreted. The people who made the disc understood the movements of the sun, moon, and stars as something patterned and reliable.

Creating the ‘firmament’, and later the ‘lights’ within it (vv. 14–18), God is establishing a sense of order within creation. Day and night, water and land, are gradually finding their proper places. The Nebra Sky Disc sits at the beginning of a long history of tools and instruments (astrolabes; monastic clocks; scientific apparatus) which likewise assume a creation orderly enough to be navigated—even if it still contains clouds of smoky verdigris and echoes of a prior chaos.

References

Lemay, Helen. 1977. ‘Science and Theology at Chartres: The Case of the Supracelestial Waters’, The British Journal for the History of Science, 10.3: 226–36

Pasztor, Emilia and Curt Roseland. 2007. ‘An Interpretation of the Nebra Disc’, Antiquity, 81:312: 267–78

Von Rad, Gerhard. 1961. Genesis: A Commentary (London: SCM)

Unknown German artist

Peapod with ten biblical scenes, c.1500, Boxwood, 10 cm long, Kunstgewerbemuseum, Staaliche Museen zu Berlin; F2497, bpk Bildagentur / Kunstgewerbemuseum / Photo by Ian Lefebvre / Art Resource, NY

Sowing Seeds

Commentary by Robert Hawkins

Around 1500, a fashion for tiny boxwood ‘prayer nuts’ blossomed in Northern Germany and the Netherlands. Wealthy patrons could commission tiny rosaries and lockets replete with moving parts and biblical scenes. This peapod is an unusual and special example: its naturalistic form contains, within its tiny hinged ‘peas’, minute scenes from the Christian story, from Adam and Eve’s disobedience to their final redemption in Christ.

The third day of creation sees the arrival of vegetation, and the text pays particular attention to seeds (Genesis 1:11–12). This is therefore the kind of world in which things reproduce: plants and animals; later, ideas and language. For now, it is fruit and vegetables that propagate, and God will offer them to humanity for food (1:29) only to revise this original vegetarianism (9:3) in light of humanity’s disobedience. Fruit becomes, of course, an emblem for humanity’s whole predicament (Genesis 3), even as the tiniest of seeds becomes a symbol for the saving power of faith (Matthew 17:20).

The boxwood prayer nuts are feats of compression, of multum in parvo, the ingenious cramming of much into a small space. Like real seeds, they are meant to contain the vital information that will enable life. Like Julian of Norwich’s hazelnut (Spearing 1998: 47), they contain the whole of salvation history, shrunk to the compass of a tiny shell. Their craftsmanship was meant to astound—just as seeds are themselves astonishing pieces of biochemistry, perfect parcels of genetic information.

The seeds within this tiny seedpod are stories. They were designed to prompt reflection on the gifts of creation and salvation. Whoever owned this, whoever carried it around with them, thumbing its smooth curves and playing with the tiny scenes inside, they hoped that these stories would take root deep within them, and one day bear fruit.

References

Scholten, Fritz (ed.). 2016. Small Wonders: Late-Gothic Boxwood Micro-carvings from the Low Countries (Amsterdam: Rijksmuseum)

Spearing, Elizabeth(trans.). 1998. Julian of Norwich: Revelations of Divine Love (London: Penguin)

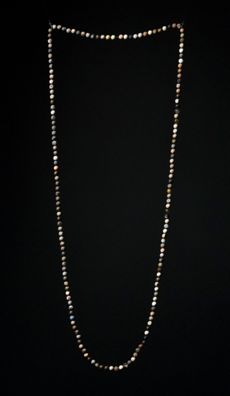

Katie Paterson

Fossil Necklace, 2013, 70 carved rounded fossils, strung on silk, 1473mm total length, 737mm end to end strung; Katie Paterson, Fossil Necklace, 2013. Photo: ©️ Thomas Farnetti Courtesy of Wellcome Collection

Let There Be Life

Commentary by Robert Hawkins

This necklace threads together one hundred and seventy beads, each one made from a different fossil. The fossils span 4750 million years of the earth’s history; the beads, arranged chronologically around the necklace, tell the story of life on earth. From its single-cell origins, through massive extinction events and the collision of continents, to the rise and fall of kingdoms of plants, reptiles, and mammals: aeons of life’s story are excavated, smoothed, and strung together.

The fifth day of creation (Genesis 1:20–23) stresses the sheer abundance of life, its multifariousness, its complexity. The waters swarm; there are creatures of every kind. Fossil Necklace helps us to imagine this phenomenal proliferation extended through geological time. What Genesis renders as a sudden blossoming, the fossil record magnifies and dilates. The chronological scale is dizzying. Each bead is a capsule from a particular day in the life of creation, an anchor attaching the present to an ancient moment in the geological story.

Creation proceeds by multiplication, and by accretion, layer upon layer. Annie Dillard, in her great meditation on the complexity of nature, Pilgrim at Tinker Creek, wonders at the sheer profligacy of it all, the extravagance of all these swarming things dying to make way for new things: ‘though nothing is lost, everything is spent’ (Dillard 1974: 66). Fertility and death have always been related: everything that lives stands on the shoulders of everything that has died. And yet, nothing is ever quite lost. Things leave prints and traces; sometimes fossils of astonishing beauty. Each of Katie Paterson’s beads is a swirling world in itself: lichen yellow, glowing amber, sparkling quartz.

Still today, the animal, plant, and fungal kingdoms roil forward in ongoing creation. As one hymn puts it: ‘there is grace enough for thousands of new worlds as great as this’.

References

Dillard, Annie. 2011. Pilgrim at Tinker Creek (London: Canterbury Press)

Unknown artist :

The Nebra Sky Disk, c.1800–1600 BCE , Bronze and gold

Unknown German artist :

Peapod with ten biblical scenes, c.1500 , Boxwood

Katie Paterson :

Fossil Necklace, 2013 , 70 carved rounded fossils, strung on silk

What a Wonderful World

Comparative commentary by Robert Hawkins

These middle days of creation are crammed with activity: earth, sea, and sky are given shape, becoming habitable. Creation proliferates, becomes complex, and finds its patterns and structures. The plain rhythm of the days, juxtaposed with the sheer scale of the fabrication, creates a sense of grandeur and the sublime.

Each of these three objects shares something of this mixture of simplicity and grandeur. The relatively unadorned materials (bronze, boxwood, stone) somehow prompt a sense of awe at the sheer existence of created matter: as Teilhard de Chardin puts it, we notice something which ‘shines’ at the heart of all matter (Teilhard de Chardin 1978: 17). Two of these objects reach way back in time: to bronze age humanity (Nebra Sky Disc) and to the earth’s deep geological past (Fossil Necklace). Even the comparatively recent material (Boxwood Peapod) is a wonder in terms of its facture: impossibly small and intricate, it echoes the compound intricacy of creation, swarming with story, pregnant with possibility.

Even here at the beginning, creation is already meaningful. It contains the seeds of the story, seeds that will bear fruit. Whereas today’s secular humanism sees the universe becoming meaningful and interesting only with the flourishing of human life, Genesis 1 describes a universe that in its first days is good already, even if it also points towards a consummation. The lights in the firmament (Genesis 1:14) are already purposeful: they are for something, carrying information, ‘for signs and for seasons, for days and for years’. Our three objects, too, are informative artefacts, meant to be used: to be carried around, worn, and read. The story of creation is itself a story with a use: carried around and metaphorically ‘worn’, it has the potential to change our whole relationship to the world.

Part of creation involves the establishing of order: other biblical texts emphasize this even more strongly, with God enclosing the waters behind the firmament’s bounds, establishing limits (e.g. Job 38:11; Proverbs 8:29). Our three artworks echo this desire for an orderly universe: the Fossil Necklace project is taxonomical, bringing chronological order to what was once a jumble of sediments and deposits, while the Sky Disc’s method is cartographical, reading off angles and arcs. The Fossil Necklace and the Boxwood Peapod, like the Genesis text itself, divide their complex stories into little roundels of meaning, each one a miniature episode of significance. And all three assume that there is a logic underlying creation (a ‘logos’, as John’s Gospel puts it) which can be discerned and investigated. Throughout human history, people have shared this sense, that this is a world that can be read and interpreted.

But there is also a wild beauty to creation. The Fossil Necklace has a neo-Romantic flavour, which it shares with Katie Paterson’s other work contemplating the vast expanses of space and time. She has made lightbulbs that glow with the quality of moonlight (Light bulb to Simulate Moonlight, 2008), and a mirror ball faceted with thousands of images of solar eclipses (Totality, 2016). In these creations, we might see the Psalmist’s sense of wonder: ‘When I look at your heavens, the work of your fingers … what are humans that you are mindful of them?’ (Psalm 8:3–4). From the cosmic perspective of deep time, the human drama that will occupy the rest of Scripture is but a drop in the bucket: this realization makes that drama all the more precious and poignant.

And even on these first days, the seeds of the story have already been sown: the grand narrative, of gift and its right response, of covenant, expectation, and fulfilment, is already underway.

References

Hague, René (trans.). 1978. Pierre Teilhard de Chardin: The Heart of Matter (San Diego: Harcourt)

Jennings, Willie James. 2019. ‘Reframing the World: Toward an Actual Christian Doctrine of Creation’, International Journal of Systematic Theology,.21.4: 388–407

Commentaries by Robert Hawkins