Genesis 1:24–31

The Sixth Day of Creation

Works of art by Lucas Cranach the Younger, Michelangelo Buonarroti, Monogrammist MS and Unknown artist

Lucas Cranach the Younger and Monogrammist MS

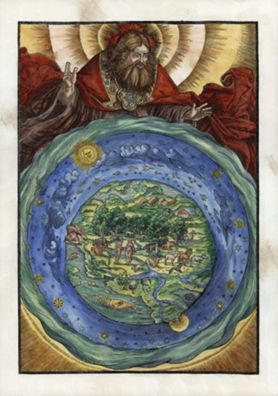

The Creation of the World, Endpaper from Wittenberg Luther Bible of 1534, 1534 (coloured later), Woodcut, Der Herzogin Anna Amalia Bibliothek, Klassik Stiftung Weimar; Bd. 1, fol. 8v, akg-images

An Overture to the Bible

Commentary by Hywel Clifford

This woodcut, with later additions in watercolour, appeared in the first complete edition of Martin Luther’s translation of the Bible. Its concentric spheres recall classical cosmologies such as the Ptolemaic system, as well as more recent iconography (like that in The Nuremberg Chronicle of 1493).

But direct simplicity was Luther’s wish. In the words of Christopher Walther (c.1515–74), one of the editors of the Wittenberg Bible, Luther ‘would not tolerate that a superfluous and unnecessary thing be added, that would not serve the text’ (Füssel 2009: 31). This was partly for pedagogical reasons, and matched Luther’s robust vernacular translation from Hebrew and Greek (not Latin), which contributed to a standardised High German and a national cultural identity. The 117 illustrations in the full edition, commissioned by Christian Döring and printed by Hans Lufft, gained quasi-canonical status—especially in Protestant homes.

Luther began to deliver his Lectures on Genesis the year after this Bible was published. Discussing the poetic prose of Genesis 1:26–28, Luther described ‘the Creator’s rejoicing and exulting over the most beautiful work He had made’—humankind (Pelikan 1958: 68). This benevolent delight is signalled by the priestly benediction of an enrobed God, who is not inside the cosmic spheres but transcends them in heavenly glory. No merely geocentric convention, the illustration celebrates the outstanding primordial miracle: a paradise of vibrant and harmonious life poised in remarkable suspension at the divine command. Its resplendent grandeur—on a full-page folio before the text of Genesis begins—is an apt overture to the Bible.

The printed text features an inset vignette of the expulsion from Eden. Indeed, close inspection shows that the unidentified artist (known as the Monogrammist MS due to the ornamental initials on the woodcuts) hints at the Fall of humanity here as well. Adam and Eve, menlin … frewlin (‘little man… little woman’, not ‘male… female’) in Luther’s translation of Genesis 1:27, converse in holy innocence and wisdom—but a serpent rises menacingly nearby. Luther’s Lectures reiterate what was tragically lost in their Fall, but also that salvation restores the divine image and likeness.

This initial scene nevertheless gladdens the heart. Its strong colours and pleasing design convey enchantment at providential ordering for animal and human life—with food for all. ‘God saw everything that he had made, and behold, it was very good’ (Genesis 1:31).

References

Füssel, Stephan. 2009. The Bible in Pictures: Illustrations from the Workshop of Lucas Cranach: A Cultural-Historical Introduction (1534) (Hong Kong: Taschen)

———. (ed.). 2016. Biblia: The Luther Bible of 1534: Complete Facsimile Edition from the Workshop of Lucas Cranach, 2 vols, plus supplement (Cologne: Taschen)

Pelikan, Jaroslav (ed.) 1958. Martin Luther Lectures on Genesis: Chapters 1–5, Luther’s Works, vol. 1 (St Louis: Concordia Publishing House)

Michelangelo Buonarroti

The Creation of Adam, c.1512, Fresco, 2.8 x 5.7 m, Sistine Chapel, Vatican Palace, Vatican State; incamerastock / Alamy Stock Photo

Animating Adam

Commentary by Hywel Clifford

To stand at the entrance to the Vatican’s Sistine Chapel (from where the figures in the ceiling appear upright) is to see a breath-taking visual scheme in which historical personae—biblical and pagan—are presented as preparing for Christ. Thus, with High Renaissance exuberance, this chapel in the papal Apostolic Palace brings the story of salvation to life.

At six metres long, the famous fresco of the creation of Adam does not seem large in the context of the greater scheme, which displays 300-or-so figures spread over approximately 500 square metres. It takes its place within a series of nine panels about creation in Genesis, beginning with God’s separation of light from darkness. A languid, expectant, and youthful Adam face to face with God (and contrasted with a drunken, disgraced, elderly Noah later in the sequence) is one of three panels about Eden and the Fall.

Comparison between the figures of God and Adam is invited by this scene, for which Michelangelo had recent models (e.g. Lorenzo Ghiberti, Paolo Uccello, Jacopo della Quercia). The creator, wise in old age with focused intent, is clothed and in flight, surrounded by angels (possibly including Eve) in a billowing red cloak. Adam, with the muscularity of a classical statue, and full of innocence and potential, is passive, earthbound, naked, alone—but the creature is attentive to his fatherly creator. This optimistic portrayal of the Imago Dei offers no stark or demeaning contrast but an intimate asymmetry that signals God’s desire to help a yearning humanity: ‘a whole history of the world in brief’ (De Tolnay 1945: 2.35).

God’s approach and arrival presages Adam’s animation: the impartation of a blessed life and consecrated purpose. In this fine example of disegno (Italian for ‘design’: the capacity for divine-like artistry and intellectual imagination), two index fingers—just about to touch due to God’s momentum—have linear flow and exquisite poignancy. Ascanio Condivi, an early biographer and friend of Michelangelo stated: ‘with His hand God is seen as giving Adam the precepts for what he should do and not do’ (King 2002: 229). Among the most parodied of all artworks, this energetic encounter of dynamic precision and tenderness calls upon the viewer—in imitation of Michelangelo’s reimagining of Genesis—to a freshly-discovered sense of self and destiny.

References

De Tolnay, Charles. 1945. The Art and Thought of Michelangelo, 2 vols (Princeton: Princeton University Press)

King, Ross. 2002. Michelangelo and the Pope’s Ceiling (London: Chatto and Windus)

Wind, Edgar. 2000. The Religious Symbolism of Michelangelo: The Sistine Chapel, ed. by Elizabeth Sears (Oxford: OUP)

Unknown artist

Tapestry of Creation (The Girona Tapestry), 11th century, Tapestry, 365 x 470 cm, Girona Cathedral; imageBROKER / Alamy Stock Photo

Dominion Over All the Earth

Commentary by Hywel Clifford

It was a staple of medieval art to portray an exalted Christ. Here, enthroned at the centre of a great ‘tapestry’ (in fact, wool-embroidered linen), an eternally youthful, beardless Christ presides as the supreme ‘image … [and] likeness of God’ (Genesis 1:27). Christ is described in the New Testament in such terms, and as the source of light and life (Colossians 1:15–17; John 1:1–5), he blesses and unites creation. Angels are in attendance above him, framing the Holy Spirit in the form of a dove. Below him we see the first humans, and animals—including a unicorn—some of whom look to Adam for their names. Excerpts from Genesis in Latin identify the scene: the outer circle begins with 1:1 and ends with 1:31; the inner circle quotes from 1:3.

Various motifs in the work have Classical precedents. At the cardinal points of the inside corners are personifications of the wind gods (anemoi) blowing trumpets. The outer rectangle has the year (annus) at the top, flanked by the agricultural seasons, and the Labours of the Months—planting in April, for instance. Sunday (dies solis) rides a chariot at the lower-left.

The tapestry also shows debts to early medieval and Carolingian-era tropes. The design recalls Isidore of Seville’s On the Nature of Things (612–15 CE), later popularly called The Book of Wheels for its diagrams of the cosmos. The eighth-century Wessobrunn Prayer Book, known in northern Spain, depicted what is just visible below: the legend of the Discovery of the True Cross by St Helena, mother of Emperor Constantine.

The tapestry’s impressive design represents more than skill in the service of a patron’s luxury. A window on both salvation and society, it might have been an altarpiece or canopy for the eucharistic celebration of the Mass. The implicit association of an authoritative Christ in heaven above—dressed in a Roman tunic and toga—with a Roman emperor’s exemplary piety on earth below points to the political: Girona was reconquered from the Moors by the Franks under Charlemagne in 785 CE, after whom the cathedral’s Romanesque northern bell-tower was named (Baert 1999). This monumental work of capacious scope and vivacious detail, incomplete but preserved in the cathedral’s museum, is eminently suited to its topic: ordered life in the cosmos.

References

Baert, Barbara. 1999. ‘New Observations on the Genesis of Girona (1050–1100): The Iconography of the Legend of the True Cross’, Gesta, 38.2: 115–27

Morales, Esther E. 1993. ‘Creation Tapestry’, in The Art of Medieval Spain AD 500–1200, ed. by H. N. Abraham (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art), pp. 309–12

Patton, Pamela A. 2012. ‘Girona Creation Tapestry’, in The Grove Encyclopedia of Medieval Art and Architecture, vol. 3, ed. by C. Hourihane, pp. 17–18

Lucas Cranach the Younger and Monogrammist MS :

The Creation of the World, Endpaper from Wittenberg Luther Bible of 1534, 1534 (coloured later) , Woodcut

Michelangelo Buonarroti :

The Creation of Adam, c.1512 , Fresco

Unknown artist :

Tapestry of Creation (The Girona Tapestry), 11th century , Tapestry

Creation Completed

Comparative commentary by Hywel Clifford

These artworks explore a foundational biblical motif: humans created in the ‘image … [and] likeness’ of God (Genesis 1:26). This enables their own imitation of primal divine creativity.

In response to God’s instructions, certain activities exemplify this: procreation and dominion. But—integrated as it is within what one modern commentator called a ‘majestic festive overture’ (Westermann 1984: 93)—the narrative of the sixth day of creation could not fail to inspire sublime artistic creativity as well. From a wealth of responses over many centuries, the three artworks chosen here invite an intriguing trans-European conversation about artists’ responses to the biblical text (De Capoa 2004: 11–25).

They have an important aspect in common. Day 6 (Genesis 1:24–31) describes creation’s completion in ways that look back to previous days while developing new details. Just as Day 4 corresponds to 1, and Day 5 to 2, so Day 6 corresponds to 3: what lives on the earth. Other literary developments—notably the expression ‘very good’ (tov meod) about ‘all things’ (v.31; cf. vv.4,10, etc.)—also encourage reflection about God as the supreme creator, and creation as a profusion of life and delight. It is no surprise, then, that this synoptic view of God’s works became a stimulus in all three artworks to capture not just one day, but the cumulative effect of the creation narratives.

They all portray the divine. Given biblical injunctions (idol prohibition) and doctrinal analysis (God’s ineffability), this was rare in early Christianity, as in Judaism. Though initially minimal, like the motif of ‘The Hand of God’ (for example, at San Vitale, Ravenna), fuller depictions emerged despite iconoclastic controversies. That New Testament texts designate Jesus Christ—the supreme ‘image … [and] likeness’—as the incarnate icon (eikōn) of God, had already provided new perspectives in an originally Jewish setting averse to depicting the divine at all. It is the fruit of such theological and artistic developments that we see in this exhibition. We ought not to assume that their artists were deliberately transgressive in this regard: their purpose was to enrich faith via illustrative, symbolic realism.

Their settings, whether in a Papal palace or on a Protestant page, mark them out as Christian. They do not interpret Genesis with reference to the book’s origins, as in modern Biblical Criticism. Rather, biblical verses are given frames of reference that are distinctively Christian. Just as God’s use of the first-person-plural form ‘let us … our’ (Genesis 1:26) was perceived by early Christian exegetes as a revelation of ‘the Trinity of the Unity, and the Unity of the Trinity’ (Augustine, Confessions 8.22), so the imago dei—that which distinguishes humankind from other earth-bound creatures (1:24–31; cf. 2:7)—was deployed as a key idea to explain salvation in Christ. The Adam–Christ typology, for example, signalled spiritual renewal (Romans 5:12–21; 12:2; 1 Corinthians 15:45–49). In these artworks such ideas are visually explored.

These artworks may also be brought into more direct historical conversation. There is a reference in the travel log for February 1538 of a visit to Girona by the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V (1500–58 CE): he wanted to see the tapestry’s portrayal of the Emperor Constantine. This is the same Charles who, when king of Germany, had declared Martin Luther an outlaw at the Diet of Worms (1521). But another ruler of the Germanic territories—Prince Frederick III, the Elector of Saxony—secured safe passage for Luther, and it is he to whom the Luther-Bibel is dedicated. The woodcut and the fresco were made within twenty-five years of each other, and in a period of growing Protestant influence that might just be discernible even in Michelangelo’s work (Hall 2004).

Tapestry and fresco required privileged ‘pilgrims’ to come to them. By contrast, the more portable book form—reproducible via the printing press—made printed artworks significantly more accessible to a wider range of people. Though restricted to a page in a Bible, with the inevitable lack of a public liturgical church setting for its elucidation, this medium presented an opportunity for the diffusion of sacred teaching in visual form in juxtaposition with the written word of God. The powerful reach of the internet is a contemporary parallel to that early modern technological development.

It is often supposed that pre-moderns were ‘flat-earthers’; it might be presumed that these artworks confirm that outlook. This is incorrect: many ancient and medieval thinkers thought the world was spherical. Moreover, these artworks show not only visual counterpoints to this late modern myth, but they also convey sophisticated notions of God’s relationship with creation in space and time. Attempts to capture this remarkable scene—creation completed—have always required adventurous and insightful imagination. After all, the biblical authors, and subsequent commentators, understood this to be an outstanding and unique episode of inestimable significance.

References

De Capoa, Charles. 2004. Old Testament Figures in Art (Los Angeles: The J. Paul Getty Museum), pp. 12–29

Hall, Marcia. B. (ed.). 2004. Michelangelo's ‘Last Judgment’ (Cambridge: CUP)

Westermann, Claus. 1984, 1986 [1974–82]. Genesis 1–11, vols 1–2, trans. by J. J. Scullion (London: SPCK)

Commentaries by Hywel Clifford