Genesis 2:18–20

Adam Naming the Animals

Unknown artist

Adam in the Earthly Paradise, diptych valve from the Carrand Diptych, 5th century, Ivory, Museo Nazionale del Bargello, Florence; n.19 C, George Tatge / Alinari / Art Resource, NY

An Apostolic Adam

Commentary by Henry Maguire

The Carrand Diptych, now in Florence, is composed of two panels of ivory (Shelton 1982; Konowitz 1984). Its classical style relates it to carvings produced at the turn of the fifth century, but its origin, whether Italy or Constantinople, is unknown. The sizes and frames of the two panels indicate that they were designed as a pair.

The left wing portrays Adam making a gesture of speech with his right hand as he names the animals in Paradise (Genesis 2:19–20). He sits in a landscape containing fruit-bearing trees and, at the bottom, the four Rivers of Paradise (Genesis 2:10–14). Adam’s relaxed pose and explicit nakedness illustrate verse 25, which states that in his prelapsarian state he was naked and not ashamed. Around him cluster the various animals that he is naming, including the serpent, which arches its back because it has not yet been condemned to crawl upon its belly as punishment for tempting Eve. Adam has no fear of even the fiercest creatures, such as the great lion just beneath him, because before the original sin the animals in Paradise were totally peaceable.

The diptych’s right panel represents scenes from the life of Paul the Apostle, who is shown balding, as is customary in traditional depictions of the saint. At the top, the apostle sits between two men, who listen to him as he makes a gesture of speech. The middle register illustrates the miracle of Paul and the viper on Malta (Acts 28:2–6). The apostle stands on the left, his hand being bitten by the snake that has come out of the small fire shown at his feet. Beside him, Publius, the governor of the island, raises his right hand to indicate his astonishment that no harm has befallen the saint. In the bottom register the apostle heals the sick of the island, including the emaciated father of Publius (Acts 28:7–9).

At first sight, the subjects of this pair of panels appear unrelated, but—as we shall see in our comparative commentary—there is great significance in the pairing.

References

Konowitz, Ellen. 1984. ‘The Program of the Carrand Diptych’, The Art Bulletin, 66.3: 484–88

Shelton, Kathleen J. Verfasser. 1982. ‘The Diptych of the Young Office Holder’, Jahrbuch Für Antike Und Christentum: 32

Unknown Venetian artist

Adam Naming the Animals, detail from the Creation, 13th century, Mosaic, Basilica di San Marco, Venice; Scala / Art Resource, NY

The Emperor with No Clothes

Commentary by Henry Maguire

This mosaic is one of a series of scenes in the southernmost dome of the atrium of San Marco in Venice portraying the story of the Creation and Fall (Demus 1984, vol. 2). Several of the episodes from Genesis depicted in the atrium were based by the mosaicists on the miniatures in the Cotton Genesis, a fifth-century manuscript that was in Venice during the thirteenth century. However, the Naming of the Animals appears to have been one of the subjects that was already missing from the book when it was in Venice, so that the artists had to create the composition themselves (Kessler 2014: 78–81).

At San Marco we see God enthroned on the left as he raises his hand to direct Adam to name the beasts arrayed before him. Adam stands in a paradisiacal landscape containing trees and flowering plants. He is shown entirely naked. He holds out the index finger of his right hand as he gives the animals their names, while resting his left hand upon the head of a grimacing lion, as if to pat a tame dog. The other creatures include both domestic and wild animals, including leopards and bears, as well as horses, sheep, and camels. The pairing of the animals anticipates the creation of Eve, in illustration of the last words of Genesis 2:20 (KJV):

And Adam gave names to all animals, and to all the fowl of the air, and to every beast of the field; but for Adam there was not found an help meet for him.

Adam’s standing pose may reflect his mastery over the creatures, since Early Christian writers such as Gregory of Nyssa claimed that Adam’s upright posture was a sign of his royal power over the beasts (Migne 1857–66, vol. 44, col. 144).

References

Demus, Otto. 1984. The Mosaics of San Marco in Venice, 2 vols (Chicago: University of Chicago Press)

Kessler, Herbert L. 2014. ‘Thirteenth-Century Venetian Revisions of the Cotton Genesis Cycle’, in The Atrium of San Marco in Venice: The Genesis and Medieval Reality of the Genesis Mosaics, ed. by Martin Büchsel, Herbert L. Kessler, and Rebecca Müller (Berlin: Gebr. Mann Verlag), pp. 75–94

Migne, Jacques-Paul. 1857–66. Patrologiae Cursus Completus, Series Graeca, 161 vols (Paris)

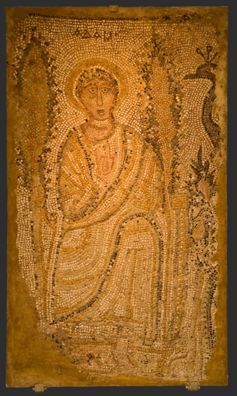

Unknown artist

Adam in Paradise, 5th century, Mosaic, Nationalmuseet, Copenhagen; Niels Poulsen mus / Alamy Stock Photo

Once and Future Glory

Commentary by Henry Maguire

The National Museum in Copenhagen preserves part of a fifth-century floor mosaic that was lifted from a church in Syria (Trolle 1971). In the surviving fragment Adam, identified by the letters above him, sits on a backless throne with a footstool, raising his right hand in a gesture of speech as he names the animals. He is flanked on either side by two cypress trees and on the right by a peacock, of which only the blue neck and crested head are preserved.

The original appearance of the entire mosaic can be ascertained with reference to a pavement of the same subject that was excavated in the nave of another fifth-century Syrian church, at Huarte (Canivet 1975). Here, at the eastern end of the nave, Adam was portrayed in the same way as in the fragment in Copenhagen, on a backless throne, between two cypress trees, and making the gesture of speech. In the Huarte mosaic Adam was surrounded by a wide variety of animals, including two snakes wreathed around the cypress trees, a lion, a lioness or a leopard, a jackal, a bear, and a mongoose. Among the winged creatures were a griffin, an eagle, a falcon, and a phoenix with rays around its head. While several of these animals had a reputation for ferocity, in the mosaic at Huarte they approached Adam peaceably. Even the mongoose was not portrayed attacking its traditional enemy, the serpent.

Since the animals at Huarte were shown at peace, both with Adam and with each other, there is little doubt that the mosaics at Huarte and Copenhagen were intended to portray the Earthly Paradise, before the original sin. But the mosaics incorporate one striking anachronism, for in both pavements Adam was portrayed fully clothed in a white tunic and mantle. He is not naked, as the biblical text requires (Genesis 2:25). Might this first Adam already prefigure a second?

References

Canivet, Maria-Teresa, and Pierre Canivet. 1975. ‘La Mosaïque d’Adam Dans l’église Syrienne de Hūarte’, Cahiers Archéologiques, 24: 49–70

Trolle, S. 1971. ‘Hellig Adam i Paradis’, Nationalmuseets Arbejdsmark: 105–12

Unknown artist :

Adam in the Earthly Paradise, diptych valve from the Carrand Diptych, 5th century , Ivory

Unknown Venetian artist :

Adam Naming the Animals, detail from the Creation, 13th century , Mosaic

Unknown artist :

Adam in Paradise, 5th century , Mosaic

Intimations of Immortality

Comparative commentary by Henry Maguire

Augustine, in his commentary on Genesis, distinguished between three different approaches to the biblical account of Paradise: corporeal, spiritual, and the two in combination (Migne 1844–80: vol. 34, col. 371). The depictions of Adam naming the animals in the three works of art presented here correspond to Augustine’s categories (Maguire 1987).

The thirteenth-century mosaic in San Marco is primarily a ‘corporeal’ account of the story that does not invite the viewer to go beyond the literal sense of the narrative. Except for Adam’s upright pose, which may signify his command over the beasts, there is little in the image to encourage us to allegorize the story.

On the other hand, the mosaic in Copenhagen forces the viewer to comprehend the ‘spiritual’ meaning of the episode by presenting Adam fully clothed, contrary to the biblical text. In this case it is clear that the artist intended to convey some level of meaning beyond simple narrative.

One possibility is that this fifth-century mosaic presents Adam in the guise of Christ, the New Adam. An objection to this interpretation, however, is that it would require the image of Christ to be placed upon the floor, where it could be trampled. Rather than portraying Christ, it is more likely that the clothing of Adam evoked the salvation of Christians. The fourth-century Syrian writer Ephrem, for example, said that the white robes of those baptized in the Church represented the spiritual robes of glory lost by Adam and Eve when they were expelled from Paradise. Speaking of the assembly of saints, he declared that:

There is not one naked person among them; glory clothes them again. None here is only covered by leaves, or standing in an attitude of shame. Our Lord himself has caused them to find the tunic of Adam again. ... Behold, those who had lost their own vestments are [clothed] anew in white. (Lavenant 1968: 84–5)

Thus we may interpret the image of Adam in the mosaics as an allegory of those who have recovered through Christ the paradisiacal state in which wild beasts and serpents cannot hurt them.

The Carrand Diptych, with its striking juxtaposition of Adam in Paradise and Paul in Malta, embodies the third of Augustine’s categories of meaning, namely the combination of the corporeal and the spiritual. The two wings can be read in a literal sense, but viewed together they suggest an allegory of Adam’s dominion over the animals as a type of the just man who has ascended from his corporeal nature to a spiritual paradise. Taking his cue from St Paul’s vision of the third heaven (2 Corinthians 12:2–4), Ambrose of Milan wrote in the fourth century that a just man, such as Paul, can ascend to the third heaven and thus be brought into a spiritual paradise where he may judge all things (Schenkl 1897: 265, 308–10).

Ideas of this kind underline the juxtaposition between the seated figures of Adam and Paul at the top of the ivory diptych, with their respective gestures of speech; Adam discriminates between the creatures, while Paul exercises his judgement in the spiritual realm. The pairing of the serpents on each side of the diptych can be explained in the words of the fifth-century theologian Theodoret of Cyrus, who wrote that:

Those who are educated in virtue do not fear the attacks of wild beasts, inasmuch as the beasts stood beside Adam before he sinned and offered their submission… In like manner the viper, which fastened its teeth on the hand of the apostle, when it found no weakness or softness of sin in him, immediately leaped off and threw itself down into the fire. (Migne 1857–66: vol. 80, col. 97)

The works of art presented here correspond to the three types of meaning listed by St Augustine. The mosaic in San Marco presents a single uncombined image with few pointers to an allegorical reading. The Carrand Diptych invites a double interpretation, for in its case each of the two juxtaposed images allows literal readings, but they also suggest allegorical content when they are combined. Finally, the Syrian mosaic does not allow a literal interpretation at all, since it contradicts the biblical text. Here, as the image is contemplated, the viewer is forced to rise from the literal interpretation and to be mindful of allegory.

Like Ephrem’s description of our human journey back to glory, this pathway is nothing less than a spiritual ascent.

References

Canivet, Maria-Teresa, and Pierre Canivet. 1975. ‘La Mosaïque d’Adam Dans l’église Syrienne de Hūarte’, Cahiers Archéologiques, 24: 49–70

Demus, Otto. 1984. The Mosaics of San Marco in Venice, 2 vols (Chicago: University of Chicago Press)

Kessler, Herbert L. 2014. ‘Thirteenth-Century Venetian Revisions of the Cotton Genesis Cycle’, in The Atrium of San Marco in Venice: The Genesis and Medieval Reality of the Genesis Mosaics, ed. by Martin Büchsel, Herbert L. Kessler, and Rebecca Müller (Berlin: Gebr. Mann Verlag), pp. 75–94

Konowitz, Ellen. 1984. ‘The Program of the Carrand Diptych’, The Art Bulletin, 66.3: 484–88

Lavenant, René (trans.). 1968. Ephrem de Nisibe. Hymnes sur le Paradis, Sources chrétiennes, 137 (Paris)

Maguire, Henry. 1987. ‘Adam and the Animals: Allegory and the Literal Sense in Early Christina Art’, Dumbarton Oaks Papers, 41: 363–73

Migne, Jacques-Paul. 1844. Patrologiae Cursus Completus, Series Latina, 221 vols (Paris)

———. 1857. Patrologiae Cursus Completus, Series Graeca, 161 vols (Paris)

Schenkl, Carolus (ed.). 1897. Sancti Ambrosii Opera, Corpus Scriptorum Ecclesiasticorum Latinorum, 32 (Vienna)

Shelton, Kathleen J. Verfasser. 1982. ‘The Diptych of the Young Office Holder’, Jahrbuch Für Antike Und Christentum: 32

Trolle, S. 1971. ‘Hellig Adam i Paradis’, Nationalmuseets Arbejdsmark: 105–12

Commentaries by Henry Maguire