Genesis 1:1–2

In the Beginning

Giovanni di Paolo

The Creation of the World and the Expulsion from Paradise, 1445, Tempera and gold on wood, 46.4 x 52.1 cm, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; Robert Lehman Collection, 1975, 1975.1.31, www.metmuseum.org

Starting Time

Commentary by Ittai Weinryb

Between God and the creature is the same difference as between a consciousness in which all the notes of a melody are simultaneously present, and a consciousness that perceives them only in succession. (Hausheer 1937: 504)

Giovanni di Paolo painted this panel as part of the predella (the lowermost horizontal component) of his now fragmented Guelfi Altarpiece for the Basilica Cateriniana di San Domenico in Siena, the central panel of which is now in the Galleria degli Uffizi in Florence.

The panel breaks away from pictorial conventions of narrative and space. The composition itself comprises two scenes, one dealing with the creation of the earth and the other with the expulsion of Adam and Eve from the Garden of Eden. God the creator descends from the upper left corner of the panel. In the heart of the cosmic disc is a world map showing the concentrated rocky earth of the interconnected four continents devoid of any cities or other human creations. It is surrounded by seven spheres. The four internal ones mark the Aristotelian elements from which everything in the world was believed to have been created (earth, wind, fire, and water). The other spheres represent the known planets, while the outermost sphere depicts the signs of the zodiac.

The bringing of the world into being is thus depicted on the left side of the panel as if it were the work of an instant. It is as though time—as creatures know it—is compressed rather than spread out in the moment of creation. Time (because part of creation) is present to God all-at-once: whole and entire.

By contrast, the right side of the panel shows ‘transitory’ time being set in motion as the angel expels Adam and Eve. Still within the Garden of Eden, in which the flora are rendered in exacting detail, the first man and woman are forced to step towards the edges of the composition, and so out of paradise. Their actual paces mark the beginning of fallen time.

Thus the instantaneity of creation, marked by God placing his finger on the sphere to forge the world in the moment before the Anthropocene, is matched with the expulsion from the garden, marked by humans’ treading of the earth. These first steps out of Eden begin to beat the rhythm to which all temporal cycles of life and death, emergence and decay, will march.

References

Hausheer, Herman. 1937. ‘St Augustine's Conception of Time’, in The Philosophical Review, 46.5: 503–12

Unknown artist [Paris]

God as Creator of the World with a Compass, from the Bible moralisée, c.1225–50, Body colour on parchment, 430 x 295 mm, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Vienna; Cod. 1179 HAN MAG, fol. 1v, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek

Genesis and Geometry

Commentary by Ittai Weinryb

Manuscript 1179 in the Austrian National Library in Vienna is one of four early copies of the Bible moralisée (moralized Bible) that was most likely made for the education of King Louis VIII of France (1187–1226). The manuscript opens with a spectacular full-page image of Christ as the creator.

While this is a common theme in medieval art and manuscript illumination, this page differs greatly from the standard iconography. In the folio, Christ sits enthroned—rather than assuming the standing position which was more customary—while holding the swirling cosmic disc in his lap. He wields a large compass with which he will form the universe. The compass is more prominent than in earlier variants, and the creator neither holds balancing scales, nor holds out fingers on which he may be counting. It has been argued that this shifts the image-type away from earlier associations with Wisdom 11:20 (‘thou hast arranged all things by measure and number and weight’) and towards Genesis 1 (Friedman 1974).

The compass came to be a medieval symbol of Euclidian geometry as well as Ptolemaic astronomy and geography (Friedman 1974: 422). Since Christ here employs it to make the world, this image asserts the congruence of Christian theology with scientific truth. The verse on top of the page reads: hic orbis figulus disponit singulus solus (‘Here the sole maker of the universe arranges each separate [element]’). In the circular universe, three distinct elements are visible: wind forms the outermost green layer, water is the blue undulating matter that turns into icy white closer to the centre (as if to echo contemporary medieval theories that the centre of the earth was frozen), and earth is the golden swirling material that fills the centre of the sphere.

Christ himself is seated in the gold eternal space of the heavenly realm in a quatrefoil frame held aloft by four angels, who witness the moment of creation. The red band of the frame is decorated throughout with a unique gold ornament that resembles Arabic script. The ciphers are meaningless, however. They are there to convey an air of alterity and link the moment with Eastern texts. Since most scientific knowledge at the time was translated from Arabic manuscripts, this pseudo-Islamic ornamentation evokes the language of scientific creation and lends a sense of scientific authority to the image of divine creation.

References

Friedman, John Block. 1974. ‘The Architect's Compass in Creation Miniatures of the Later Middle Ages’, in Traditio 30

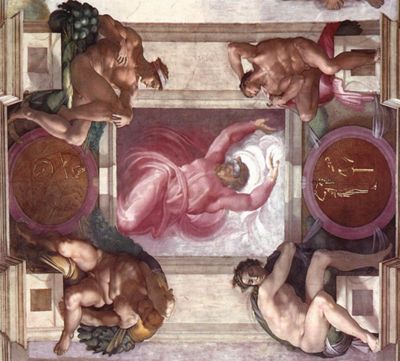

Michelangelo Buonarroti

The Separation of Light and Dark, 1511, Fresco, Sistine Chapel, Vatican City; Art Collection 2 / Alamy Stock Photo

Order from Chaos

Commentary by Ittai Weinryb

Most likely completed in 1512, Michelangelo’s fresco representing the Separation of Light from Darkness is the first of the nine central panels representing the story of Genesis on the Sistine Chapel ceiling. By choosing this scene as the first in the Cycle of Creation, Michelangelo conflates the separation of light from darkness in Genesis 1:4–5 with that of order from chaos in Genesis 1:1–2.

Darkness is shown as a formless void, from which white light, in perfect circles, is being wrested.

In the Bible, God’s announcement, ‘Let there be…’ (Genesis 1:3), seems to invite the world into being with a mere utterance, and Michelangelo inherited a traditional iconography that depicted an all-powerful deity effortlessly at work. Dramatically, the artist has broken from this tradition by portraying a robust figure straining with activity. His rendering of the scene celebrates the luminosity of the ordered world as something strenuously plucked from turbid gloom.

Michelangelo’s great challenge here was to represent an almost unimaginable event with no obvious corresponding physical action. After all, God’s power to create from nothing (ex nihilo) is not imitable by any human creature.

For a skilled artist however, the generation of form, of light, and of darkness is an essential professional skill. It is arguably the primary work of any figurative painter and especially of one who endeavours to create the seen from the unseen, the perceptible from the invisible. God created form out of chaos and summoned light out of darkness. The painter must generate light from pigments to both shape and illuminate a pictorial world. In both cases, the act of creation can be explored as an act of bringing order to the world—of creating a ‘whole’ out of a chaotic mass—and of illuminating that world.

Accordingly, we are asked to imagine Michelangelo’s God-creator as an active, virile ‘painter’. His whole body exerts itself to push the chaos and darkness away.

In representing God the Father in this way, Michelangelo imbues the biblical text and God’s actions with the emotional and physical effort of an earthly artist like himself.

Giovanni di Paolo :

The Creation of the World and the Expulsion from Paradise, 1445 , Tempera and gold on wood

Unknown artist [Paris] :

God as Creator of the World with a Compass, from the Bible moralisée, c.1225–50 , Body colour on parchment

Michelangelo Buonarroti :

The Separation of Light and Dark, 1511 , Fresco

The Divine Artist

Comparative commentary by Ittai Weinryb

‘The beginning’ is not an easy thing to visualize when it comes to the creation of the world.

Philosophers have at various times followed Aristotle in speculating that there was some sort of primal matter before God shaped from it the forms of lands, trees, animals, and even humans. Christian theologians have argued that if God was there to create the world, then he necessarily existed before the world did and created ‘the essence with the form’ (Basil, Hexaemeron 2.3).

Medieval theories of the creation of the world were made not only by theologians using medieval logic but by scholars of ‘natural philosophy’ relying on scientific texts transmitted from antiquity and translated into Latin from the original Greek or Arabic. The Arabicizing script in the frontispiece of the moralized Bible echoes this presence of Arabic science—something that was revered in western Europe at the time.

Equally revered was Plato’s Timaeus—among the most important texts employed to theorize creation. The book was the only Platonic dialogue available in Latin in the early Middle Ages and was regarded by writers such as Calcidius (fourth century), Thierry of Chartres (c.1100–c.1150), and William of Conches (c.1090/1091–c.1155/1170s) as the scientific parallel to the theological account of creation offered by the book of Genesis. As the most influential scientific explanation of creation in the European realm, the importance of the Timaeus, traditionally accompanied by a medieval Latin commentary, rivalled that of the biblical tradition.

The Timaeus was central to the crucial medieval debate on how God created the world. The text describes how the divine artifex, in accordance with mathematical conventions, created the four elements—fire, air, water, and earth—out of primordial matter (prima materia), which was in a chaotic, amorphous state, lacking all comprehensible form. The four elements then conjoined to create the world, and they continue to reside in each thing created by God, human or non-human.

In the illuminated Bible moralisée frontispiece God is shown generating the world out of just such primordial matter while seated outside it.

Michelangelo suggests a swirling primordial substance that is comparable to that in the manuscript illumination, but his God seems almost to be embroiled in the creation he seeks to form.

Giovanni di Paolo’s predella panel is different again. It is like the manuscript illumination in depicting a God who operates from ‘outside’ the world when creating it, but it seems to spring into being in perfect wholeness and order at a mere touch.

In the late fourth century, Basil of Caesarea wrote of the difference between divine creation (which is out of nothing—ex nihilo) and human creation:

Here below arts are subsequent to matter—introduced into life by the indispensable need of them. Wool existed before weaving…. Wood existed before carpentering took possession of it…. But God, before all those things that now attract our notice existed … imagined the world such as it ought to be and created matter in harmony with the form that he wished to give it. (Hexaemeron 2.2)

Despite such admonitions, it is not surprising that artists in the Middle Ages and the Renaissance were attracted to make comparisons. They would have seen something particularly engaging in the problem of how to represent the divine creator since they themselves were also in the act of creating a world. Elements of this parallel are clearly visible in all three works in this exhibition. In the frontispiece to manuscript 1179, God is shown organizing the swirling cosmic matter on his lap by brandishing a compass, the tool for mathematical calculation used by many medieval artistic creators to impose order on the blank page. The God of Giovanni di Paolo’s painting, clearly distinct from his creation, embodies an artist’s capacity to stand back from his work, whether to appraise it or direct others to admire it. Meanwhile in Michelangelo’s fresco in the Sistine Chapel, God strains with raised arms to push light from darkness in a motion akin to the human endeavour of ceiling painting.

We may, therefore, conclude that when conceptualizing the first scene in the Old Testament, artists are confronted, on the one hand, with the need to visualize things that traditionally cannot be visualized (God in an amorphous realm and primary matter that is without any form) and, on the other, with the attraction of depicting God as like a struggling artist himself, attempting to make a world that does not yet exist—a very human role that mirrored their own.

The task of the artist rendering this subject matter was difficult and important: their artistic creations justified not only their own position and livelihood in this world but also the world order and the everlasting presence of God, the divine artist.

References

Glass, Dorothy F. 1982. ‘In principio: The Creation in the Middle Ages’, in Approaches to Nature in the Middle Ages: Papers of the Tenth Annual Conference of the Center for Medieval and Early Renaissance Studies, ed. by Lawrence D. Roberts (Binghamton, NY: Center for Medieval and Early Renaissance Studies), pp. 67–104

Rudolph, Conrad.1999. ‘In the Beginning: Theories and Images of Creation in Northern Europe in the Twelfth Century’, Art History, 22: 3–55

Schaff, Philip and Henry Wace (eds). 1895. ‘St Basil, Letters and Select Works, in Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers, Second Series, Vol. 8 (New York: The Christian Literature Company)

Zahlten, Johannes. 1979. Creatio Mundi: Darstellungen der sechs Schöpfungstage und naturwissenschafliches Weltbild im Mittelalter (Stuttgart: Klett-Cotta)

Commentaries by Ittai Weinryb