Genesis 2:9–17

The Garden of Eden

Thomas Cole

The Garden of Eden, 1828, Oil on canvas, 97.8 x 134 cm, Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas; Courtesy of Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas

America the Beginning

Commentary by Andrew Hui

‘In the Beginning, All the World Was America’, John Locke wrote in his Essay Concerning Human Understanding (1689). Through the course of centuries, there have been many interpretations of the English philosopher’s evocative fantasy of the primordial state of nature. Is he celebrating freedom before property or is there a settler mentality latent in his account?

Some 150 years after Locke, Thomas Cole was only 27 years old when he painted his Garden of Eden (1828). As one of the forefathers of the Hudson River School, he celebrated the majesty of the American landscape. In Cole’s time, the project of westward expansion was in full force. Indeed, five years later Cole undertook a Grand Tour of Europe after which he painted a suite of five canvases entitled The Course of Empires, which moves from The Savage State to The Arcadian or Pastoral State, then from The Consummation of Empire to Destruction and finally to Desolation. The parallel between the fallen Roman Empire and the burgeoning American one is clear.

All of the ‘New World’ appears as a pure, unspoilt wilderness ready to be populated by a man and a woman. Cole depicts trees that are equally as lofty as the mountains, and a surging waterfall can be seen in the centre. In the foreground are colourful flora; in the babbling brook appear precious stones described in Genesis 2:12–13: gold, bdellium, and onyx stone.

The overt Romanticism of Cole’s painting might seem a bit clichéd today, anticipating the dreamscapes of an American middle-class, living-room aesthetic. On the one hand, the painting might represent the simple innocence of our first parents overwhelmed by the sublime grandeur of nature. On the other hand, a contrapuntal reading could take it as an implicit tract for (or critique of) Western expansion. What ideology underlies Cole’s aesthetic? There is no doubt that when Cole maps the Biblical Eden onto America, he imbues the new nation with a sense of destiny and providence.

Perhaps if migration was a return to humankind’s origins, America can redeem us from the expulsion from paradise. Or we might wonder whether Cole’s more subtle point is that the Indigenous peoples were the first Adams and Eves of the Americas. Expelled by the incursion of European immigrants, they become victims of yet another phase in humanity’s fallen history.

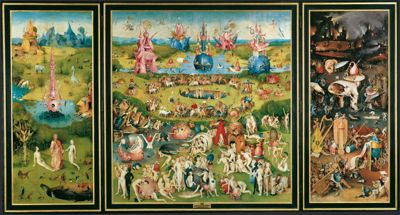

Hieronymous Bosch

The Garden of Earthly Delights Triptych, 1490–1500, Oil on oak panel, Height: 185.8 cm; Width of the central panel: 172.5 cm; Width of the wing: 76.5 cm, Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid; Album / Art Resource, NY; Photo: ©️ Museo Nacional del Prado / Art Resource, NY

Proliferating Pleasures

Commentary by Andrew Hui

Is there any painter who delights in such mind-boggling and eye-popping details as Hieronymus Bosch?

The central panel in The Garden of Earthly Delights is an exercise in proliferating multiplicity: animal, vegetal, mineral. Reading the triptych from left to right, Bosch depicts the Garden of Eden, the Garden of Earthly Delights, and finally Hell. Thus he charts the creation of two humans by one God to the procreation of many humans, and the descent into a cacophonic ‘subhuman’ multitude. What happens when one becomes two and two becomes many, and many becomes a hot, hellish mess?

In the luxuriantly detailed tour-de-force that is the central panel, Bosch gives us an encyclopaedia of creaturely desire.

Here, we see an interpenetration of living things great and small: humans appear to be animals and animals appear to be human. All permutations of copulation seem possible. Bodies are torquing, grabbing, entangled; all of creation huddled together and hankering after each other.

Genesis 2:16–17 present the primordial prohibition for the human race: ‘You may freely eat of every tree of the garden; but of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil you shall not eat, for in the day that you eat of it you shall die’. Very clearly, Bosch has gone far beyond the plain text of scripture. The humans in his garden are gluttonous, ingesting humongous strawberries, raspberries, and cherries, and even each other—wildly exceeding the simple biblical regulation.

Yet, perhaps this frenzy of consumption recognizes a deeper truth of the biblical story. The oldest surviving observation about the painting comes from Fray José Sigüenza, who called it the ‘Strawberry Plant’ in 1605 and said it was about ‘the vanity and glory and transient state of strawberries’. Bosch shows us it is just as much about the vanity, glory, and transience of sinful humans.

References

Belting, Hans. 2005. Garden of Earthly Delights (Munich: Prestel)

Koerner, Joseph Leo. 2016. Bosch and Bruegel: From Enemy Painting to Everyday Life (Princeton: Princeton University Press)

Unknown Persian artist

Carpet, 18th century, Wool knotted pile on cotton warp and wool weft, 268 x 383.5 cm, The Victoria and Albert Museum, London; T.10-1924, ©️ Victoria and Albert Museum, London

A Little History of Persian Paradise

Commentary by Andrew Hui

The history of the Persian carpet might be as old as the Bible. Already in the Achaemenid Empire (sixth–fourth centuries BCE), highly skilled weavers were producing rugs of the highest quality. Recent scholarship dates the Hebrew Bible canon to the Second Temple post-exilic period (from 516 BCE). Indeed, it is now believed by many scholars that it was during the age of Persian dominance that Judaism was organized into a distinct, unified religion.

Paradise in Hebrew is pardes and in the Persian Old Avestan language pairidaēza- means ‘a wall enclosing a garden or orchard’. When the writers of Genesis were imagining the original home of our first parents, might they have been remembering the parks where Persian nobles delighted in hunting wild game or the wilted, overgrown ruins of their former masters?

Garden and geometric designs are fundamental to Persian carpets. This splendid example from the Victoria & Albert Museum takes the traditional chahar-bagh structure (from the Persian chahar, meaning four, and bagh, meaning garden). Persian garden makers used the fourfold matrix long before their conversion to Islam, and when Muslim architects came along, they transposed the chahar-bagh to the Qur‘anic four rivers of Eden.

It is not only the design of Persian carpets that mimics real gardens. So do their materials. The coloured dyes of these opulent works were made from vegetal ingredients: pomegranate peels, eucalyptus leaves, indigo, black curd, turmeric, herbs, acorn shells, and alum. Since so much of the Middle East is a desert, to unfurl a carpet or construct a garden in the arid land was to gesture to an unattainable transcendental locus, a visible yearning for something invisible.

If gardens are fixed green monuments, then scriptures and carpets are portable gardens, nomadic objects that offer refuge from inhospitable neighbours and harsh surroundings.

References

Burns, James D. 2010. Visions of Nature: The Antique Weavings of Persia (New York: Umbrage Editions)

Stone, Peter F. 2013. Oriental Rugs: An Illustrated Lexicon of Motifs, Materials, and Origins (North Clarendon: Tuttle Publishing)

Thomas Cole :

The Garden of Eden, 1828 , Oil on canvas

Hieronymous Bosch :

The Garden of Earthly Delights Triptych, 1490–1500 , Oil on oak panel

Unknown Persian artist :

Carpet, 18th century , Wool knotted pile on cotton warp and wool weft

The Vocation of Care

Comparative commentary by Andrew Hui

A few cryptic lines in Hebrew (Genesis 2:9–17). From these precious lines spring forth carpets, paintings, myths, and more. Nature. Artifice. Humanity. God. Writing. Habitation. America. Europe. The Middle East. A whole world lies furled in these brief verses.

Genesis presents an axis mundi: two trees, and the enclosed space of a garden called Eden. Then one nameless flowing river which ramifies into four—Pison, Gihon, Hiddekel, and Euphrates. The writers of Genesis furnish a geography that describes the abundance of fruits and precious metals. The biblical verses are etiological—they give name to something that pre-existed (the rivers), and they demarcate human-made boundaries. To mention Havilah, Ethiopia, Assyria is already to suggest some sort of territory dispute.

The Persian carpet in the Victoria & Albert Museum presents a complex system of modular design. We see fractal rectangles that enclose tree and flower motifs, for the geometric and the vegetal have exponential growth functions. From the circular petal centre everything radiates forth. Carpets were luxury objects as well as liturgical ones—a Muslim uses a rug on which to pray in the direction of Mecca five times a day; there are many Persian carpets in Renaissance sacred paintings; and today many Catholic Churches in Italy and elsewhere still have them in the sanctuary.

The Bosch triptych presents scenes of riotous exposure that are revelatory of much more than a mythic past. Like many Renaissance triptychs, whether made for private meditation or for public liturgy, it was hinged. The vision of scenes of creation, delight, and cosmic undoing can only be seen though the act of closing and opening two doors. Every viewing then, enacts a spiritual disclosure.

Thomas Cole’s painting presents Eden as mapped on to the American Sublime. At the same time that Cole was conjuring up the majesty of America in his art, Tocqueville wrote in his journal:

An American thinks nothing of hacking his way through a nearly impenetrable forest, crossing a swift river, braving a pestilential swamp, or sleeping in the damp forest if there is a chance of making a dollar. But the urge to gaze upon huge trees and commune in solitude with nature utterly surpasses his understanding. (Nemerov 2023:11)

Perhaps Cole’s answer was that he did indeed gaze upon huge trees, and that in doing so he imitated what Adam and Eve had done in Eden, hand in hand, in their shared solitude.

Taken together, we see that carpets, gardens, and paintings are microcosms. As enclosed spaces, they offer a refuge from inhospitable climates; they seek to capture some permanence in the flux of time and the interchange of states.

‘In an immortal Eden there is no need to cultivate, since all is pregiven there spontaneously’, writes Robert Pogue Harrison in his meditative Gardens: An Essay on the Human Condition (2008: iii). The nameless makers of Persian carpets (almost certainly a team of women, since it was a heavily gendered craft), Bosch, and Cole all in their own ways used the Edenic story, conjuring up new Paradises in their own contexts.

If the innumerable permutations of the Edenic myth teach us anything, it is that while real gardens are rooted in place and time, the imaginary ones that are found in carpets, triptychs, and paintings might be even more potent, for they travel far and wide and can be accessible anytime and anywhere.

Eden was a gift from God, but the price humans paid after their disobedience was death, pain, and suffering. Perhaps life is only bearable when we take up the vocation of care, and this activity can be aided by thinking about scriptures, carpets, and paintings, for in so doing, we all create our own little gardens.

References

Harrison, Robert Pogue. 2008. Gardens: An Essay on the Human Condition (Chicago: University of Chicago Press)

Nemerov, Alexander. 2023. The Forest: A Fable of America in the 1830s (Princeton: Princeton University Press)

Commentaries by Andrew Hui