Luke 10:25–37

The Good Samaritan

Jacopo Bassano

The Good Samaritan, c.1562–63, Oil on canvas, 102.1 x 79.7 cm, The National Gallery, London; Bought, 1856, NG277, © National Gallery, London / Art Resource, NY

Go and Do Likewise

Commentary by David B. Gowler

Jacopo Bassano’s visual exegesis emphasizes social responsibility in an era in which many people in the environs of Venice suffered from poverty, homelessness, and food shortages. As a result, Venice and other nearby cities were besieged by a migration of homeless paupers and, in response to this societal trauma, numerous reformers in the Catholic church criticized the spiritual indifference that included neglect of impoverished people. Vincenzio Giaccaro, for example, cited the parable of the Good Samaritan to argue that Christians should meet their neighbours’ spiritual and bodily needs. Bassano’s religious paintings often clearly reflect such ethical concerns (Aikema 1996: 10, 46, 49; Hornik and Parsons 2003: 99–101).

Although the human drama of the Samaritan’s act of mercy is therefore the centre of attention here—we are shown the Samaritan’s strenuous efforts to lift the wounded man onto the animal (Luke 10:34)—the painting’s naturalism does not prevent interpreters from envisioning allegorical elements in the work. The portrayal of the victim—his body pale, vulnerable, and helpless, with wounds dripping with blood—echoes visual representations of the Deposition, when Jesus’s body was removed from the cross (De Lange 2011: 66–68). There may be a bloody bandage in the place of a crown of thorns, but the painting seems to offer an example of how showing mercy to the ‘least of these’ is the same as showing mercy to Jesus (Matthew 25:40), a symbolism that once again reminds viewers to reflect on their responsibility to assist people in need.

In addition, the Levite at the far left of the composition is shown reading (a detail not in the text), which may symbolize people who who appear to love God’s Law, but disregard its commands to love one’s neighbour. Since Bassano often included dogs in his works to illustrate religious indifference or even blameworthiness, the two dogs likely mirror the callous neglect of the priest and Levite (Luke 10:31–32).

By contrast, the Samaritan, in this dark, dangerous place, does what the Law requires (cf. Luke 16:29). He chooses the good and righteous path, and energetically offers compassion and mercy. In this way, the painting seeks to persuade its viewers, as did Jesus the lawyer, to ‘go and do likewise’ (v.37).

References

Aikema, Bernard. 1996. Jacopo Bassano and His Public (New Jersey: Princeton University Press)

De Lange, Frits. 2011. ‘Restoring Autonomy: Symmetry and Asymmetry in Care Relationships’, Ned Geref Teologiese Tydskrif, Deel 52 Supplement: 61–68

Hornik, Heidi J., and Mikeal C. Parsons. 2003. Illuminating Luke (vol. 2): The Public Ministry of Christ in Italian Renaissance and Baroque Painting (Harrisburg: Trinity Press International)

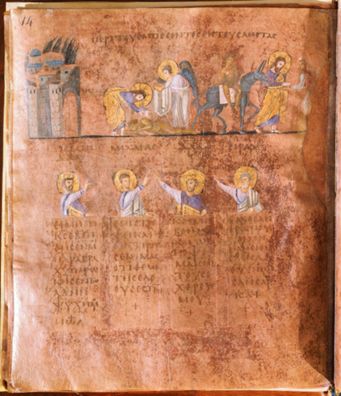

Unknown artist

The Good Samaritan, from the Rossano Gospels (Codex Purpureus Rossanensis), 6th century, Painted purple vellum, Diocesan Museum, Rossano Cathedral, Italy; Codex Purpureus Rossanensis, fol. 7, © A. De Gregorio / De Agostini Picture Library / Bridgeman Images

Samaritan Jesus

Commentary by David B. Gowler

The Rossano Gospels, the oldest extant illuminated manuscript of the New Testament Gospels, includes a full-page depiction of the parable of the Good Samaritan in a cycle of illuminations portraying Jesus’s Passion—and situates it between images of Jesus’s prayer in the Garden of Gethsemane and his healing of two blind men (on one side) and Jesus’s trial before Pilate (on the other). This placement connects notions of spiritual conversion (symbolized by the healing of the blind) with the idea of redemption through Jesus’s death.

The upper register depicts an allegorical interpretation of the parable that is read from left to right. Jerusalem, or perhaps Jericho, appears on the far left. In the middle, Jesus, as the Good Samaritan (evident by the cross nimbus), ministers to the wounded, bloody man. An angel—in a white robe, with blue wings and a halo—stands on the other side of the man and holds a bowl draped with a white cloth.

The narrative continues to the right in a second scene in which the wounded man, still naked and bloody, sits sidesaddle (making his injuries more visible to the beholder) on the Samaritan’s animal. The man watches as Jesus pays the innkeeper.

The bottom register includes two pairs of figures from the Septuagint with their names inscribed above them—David and Micah, and David and Sirach. All four figures have halos, but King David has a jewel-studded crown, darker clothes, and a breastplate. The four each hold a brief text from the Septuagint, texts that in the context of the illumination serve as prophecies about the parable and about Jesus himself. These verses all further illustrate the allegorical interpretation of the parable: Psalm 94:17 (‘If it had not been that the Lord had helped me, my soul would have sojourned in Hades’); Micah 7:19; Psalm 118:7; and Sirach 18:12 (Filareto and Renzo 2001). The four figures also point upward to Jesus as the Good Samaritan, with their fingers spelling out a four-letter abbreviation of the Greek for ‘Jesus Christ’ (IC XC).

The allegorical portrayal of the Samaritan as Jesus ensures that he is the primary focus of attention. Jesus is the one who, as prophesied in Scripture, ministers to wounded human beings, takes them to the inn/church, and pays the price for their healing/salvation (Gowler 2020: 54–58).

References

Filareto, Francesco and Luigi Renzo. 2001. Il Codice Purpureo di Rossano: Codex purpureos rossanensis (Rossano: Museo diocesano di arte sacra)

Gowler, David B. 2020 [2017]. The Parables after Jesus: Their Imaginative Receptions across Two Millennia (Waco: Baylor Academic Press)

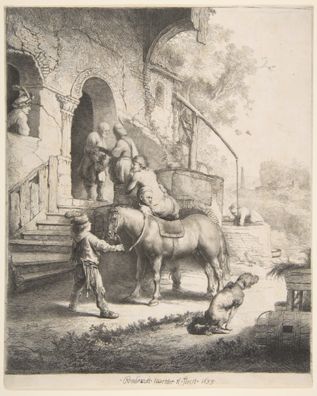

Rembrandt van Rijn

The Good Samaritan, 1633, Etching, engraving, and drypoint, 253 x 204 mm, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; Gift of Henry Walters, 1917, 17.37.192, www.metmuseum.org

Sh*t Happens

Commentary by David B. Gowler

In the centre foreground of Rembrandt van Rijn’s etching, a boy holds the reins as a servant helps the wounded man off a horse. The wounded man is shirtless, with a bandage on his head, and, above him, we see the Samaritan and the innkeeper, the latter apparently putting the denarii into his purse (Luke 10:35).

A man at a window looks at the wounded man being lifted off the horse, and the wounded man returns his gaze. Perhaps, as Goethe (1986: 68) posited, the observer at the window is one of the thieves who had robbed and beaten the man, and now the wounded man suddenly realizes he is once again vulnerable.

The inn is in a state of disrepair, and it is in this decaying and sometimes disturbing world—considering the gratuitous violence preceding this scene (v.30)—that the Samaritan’s surprising act of mercy takes place. Nevertheless, life continues as normal. A woman draws water from a well, and, in the right front foreground, a dog, with its back to us, defecates on the ground.

The centrality of the dog is striking, and the structure of the composition leads viewers from the bottom right—where the dog performs a rudimentary bodily function common to all animals—along a diagonal to the left and back—where the Samaritan, his face unseen, performs a selfless act of mercy. Such acts, the parable of the Sheep and Goats reminds us (Matthew 25:31–45), are necessary for human beings to enter the kingdom of heaven, which is why, perhaps, some are led to interpret the open door of the inn as symbolizing the way of salvation through the church (Kuretsky 1995: 150–51).

The dog most likely functions primarily as a playful marker of verisimilitude, yet it illustrates the fact that life inherently includes the sublime and the everyday, the unusual and the banal, the sacred and the profane, with the latter—in each of these polarities—often more prevalent than the former (Gowler 2020: 154–58).

References

Goethe, Johann Wolfgang von. 1986. Essays on Art and Literature, vol. 3 (New York: Suhrkamp)

Gowler, David B. 2020 [2017]. The Parables after Jesus: Their Imaginative Receptions across Two Millennia (Waco: Baylor Academic Press)

Kuretsky, Susan Donahue. 1995. ‘Rembrandt’s “Good Samaritan” Etching: Reflections on a Disreputable Dog’, in Shop Talk: Studies in Honor of Seymour Slive, ed. by William Robinson (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Art Museum), pp. 150–53

Jacopo Bassano :

The Good Samaritan, c.1562–63 , Oil on canvas

Unknown artist :

The Good Samaritan, from the Rossano Gospels (Codex Purpureus Rossanensis), 6th century , Painted purple vellum

Rembrandt van Rijn :

The Good Samaritan, 1633 , Etching, engraving, and drypoint

And Who Is My Neighbour?

Comparative commentary by David B. Gowler

The parable of the Good Samaritan challenges its hearers to reimagine themselves, the world, other human beings, and God in radically different ways—and to put that new perspective into concrete action in their daily lives. It thus teaches a moral lesson. Yet, for centuries, the dominant interpretation of the parable was as an allegory of salvation history, such as the one famously elaborated by Origen. On this account, Jesus (the true Good Samaritan) restores fallen humanity (the wounded man, who symbolizes Adam). After the man is attacked by hostile forces in the world (the thieves, who represent Satan), the Samaritan brings the man to a right relationship with God in the church (the inn) of a sort that the old dispensation (the priest and Levite) cannot provide (Homilies on Luke, 32; cf. Augustine, Questions on the Gospels, 219).

Allegorical interpretations also dominated visual representations of the parable for centuries, as we see in the illuminations from the sixth-century Rossano Gospels where Jesus is explicitly portrayed as the Good Samaritan. A fourteenth-century mural in St Catherine’s Monastery on Sinai takes the allegory even further, because Jesus himself carries the wounded man, instead of placing him on an animal: Jesus is the symbolic ‘beast of burden’ who bears upon himself the salvation of humankind. Compare the twelfth-century stained-glass window in the Cathedral of Notre Dame in Chartres, whose twenty-four images physically and theologically extend the parable as an allegory of salvation by including the fall of Adam and Eve. In these interpretations, the parable by Jesus has evolved into a parable about Jesus (Gowler 2015: 643–45).

Allegorical interpretations of the parable began to decline in importance during the Reformation. Visual representations also reflect that change in emphasis with the majority of images depicting the Samaritan assisting the wounded man, usually with the priest and the Levite walking away in the background. Jacopo Bassano’s painting, like the parable itself, emphasizes the desperate need of the wounded man and the compassionate actions of the Samaritan, with the priest and Levite serving as foils against which to contrast the Samaritan’s mercy. In this way, Bassano urges viewers to be similarly ‘moved with compassion’ (Luke 10:33).

Bassano’s painting might also serve as a reminder that performing such acts of mercy for the ‘least of these’ is considered the same as performing them for Jesus (Matthew 25:40), thus reintroducing allusions to Jesus in the parable. In this case, however, Jesus is not portrayed allegorically as the Samaritan; instead, aspects of the wounded man’s depiction may reflect Jesus’s descent from the cross. He is the one left for dead at the roadside. This change in perspective highlights the human actions necessary to inherit eternal life, while still acknowledging Jesus’s role as the instrument of salvation.

Rembrandt van Rijn’s etching portraying the Samaritan and the wounded man arriving at the inn extends the emphasis from the man’s need and the Samaritan’s mercy to the Samaritan’s additional, generous efforts to restore the man to health (Luke 10:35). The parable’s connection to compassion and healing also resulted in images of the Good Samaritan being commissioned specifically for hospitals, such as William Hogarth’s treatment of the scene for St Bartholomew’s Hospital in London.

Even elements of Rembrandt’s distinctive down-to-earth composition have been received allegorically by some interpreters, with the open door of the inn seen as symbolizing the path to eternal salvation—a passageway to eternal life (cf. 10:25) that opens for those like the Samaritan who perform such acts of mercy (Gowler 2020: 157).

Why might such naturalistic visual representations of the parable still evoke in some viewers allegorical, symbolic, or, in the words of Augustine, ‘spiritual’ interpretations? Perhaps it’s because both parables and visual images often function in a way analogous to ‘enthymemes’. Unlike syllogisms, in which explicitly stated premises lead to a necessary conclusion (e.g., All humans are mortal; Socrates is human; therefore, Socrates is mortal), enthymemes instead omit a premise (e.g., Socrates is human; therefore, Socrates is mortal), and the deliberately unstated premise has to be supplied by readers/hearers/viewers. Parables and visual images also can be ‘enthymematic’ and, since the unstated ‘premise’ is not always evident, can thus be ambiguous and polyvalent, provoking divergent responses as interpreters endeavour to understand them (Gowler 2012: 199–201, 209–13; Gowler 2020: 255–57).

The varying responses to Jesus’s parable of the Good Samaritan demonstrate how powerfully it continues to challenge people’s hearts, minds, and imaginations. The lawyer asks, ‘What must I do to inherit eternal life?’ Jesus asks, ‘Who proved to be a neighbour?’ The Rossano Gospels, Bassano, and Rembrandt respond in their own ways, and, in doing so, also challenge us to respond.

References

Gowler, David B. 2012. ‘The Enthymematic Nature of Parables: A Dialogic Reading of the Parable of the Rich Fool (Luke 12:16–20)’, Review and Expositor, 109.2: 199–217

________. 2015. ‘The Good Samaritan in Visual Art,’ in The Encyclopedia of the Bible and Its Reception, vol. 10, ed. by Dale Allison, Jr., Christine Helmer, Choon-Leong Seow, et al. (Berlin: De Gruyter)

________. 2020 [2017].The Parables after Jesus: Their Imaginative Receptions across Two Millennia (Waco: Baylor Academic Press)

Commentaries by David B. Gowler