Romans 3:9–31

Grace Works

Martin Creed

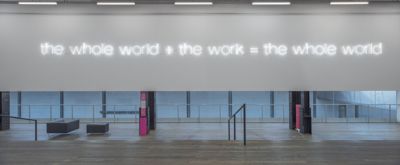

Work No. 232: the whole world + the work = the whole world, 2000, Neon lights and metal, Unconfirmed: 50 x 1550 cm, Tate; Presented by the Patrons of New Art [Special Purchase Fund] 2001, T07769, © Martin Creed. All rights reserved / DACS, London / ARS, New York © Tate, London / Art Resource, NY

Apart from Works

Commentary by Matthew Milliner

The twentieth century generated duelling crescendos of confident Modernist art and hitherto unimaginable human violence. A stalling of artistic confidence in our new millennium may have been inevitable. The career of conceptual artist Martin Creed (b.1968) illustrates this hesitation, which is perhaps best expressed in Work No. 232, comprising the words, ‘the whole world + the work = the whole world’, originally affixed in neon to the entablature of Tate Britain to inaugurate the museum’s renaming (from the Tate Gallery of British Art) in the year 2000.

Work No. 232 could be read as rebuffing the cultural ‘works’ within the museum, which add nothing of justifying substance to the global status quo. Romans 3:20 is a similar neon message irrevocably affixed to the annals of human striving: ‘no human being will be justified in his sight by works’.

This is not to say Creed’s art lacks a positive analogue corresponding to the latter section of Romans 3. Work No. 203, ‘EVERYTHING IS GOING TO BE ALRIGHT’ was another neon message appended to Tate Britain’s entablature. The work was originally conceived for the Clapton Portico in east London, and Creed explicitly attributes its inspiration to the Salvation Army ‘barracks’ that formerly occupied the ruined and then repaired building (Creed 2006). Creed’s message was deliberately placed as a palimpsest over the word ‘SALVATION’ that once covered the same entablature, as if to translate the word into a modern idiom.

It could be mindless optimism or just a cliché. It could even betray a certain anxiety. On the other hand, perhaps this ‘gospel’ side of Creed’s message, when brought into conversation with Romans 3:21–26, might be understood as a translation of the crucified God’s words to Julian of Norwich (1342–1416): ‘All things shall be well’ (2006: 23).

When both of Creed’s works were installed in Tate Modern, moreover, this law/gospel encapsulation of the tension in Romans 3 occupied the same building at once.

References

Creed, Martin. 2010. Martin Creed: Works (New York: Thames and Hudson)

Julian of Norwich. 1999. Revelations of Divine Love (New York: Penguin Classics)

TheEYE: Martin Creed. 2006. (Illuminations media)

Unknown artist

Deisis/Deësis Composition of Hagia Sophia, 13th century, Mosaic, South Gallery of Hagia Sophia, Istanbul; Pictures from History / Myrabella / Bridgeman Images

That He Might Be Just and Justifier

Commentary by Matthew Milliner

When Constantinople, once the capital of the Byzantine Empire, was finally taken back from the Latin Crusaders in 1261, it is fitting that a newly commissioned mosaic in its chief church would employ a venerable Byzantine theme, the Deësis (which is also, in Greek, a more general word for intercession). With a haunting human tenderness that anticipates (and indeed inspired) subsequent developments during the Renaissance, anonymous Byzantine mosaicists revisited this theme on a massive scale in the south upper gallery of the city’s chief church, Hagia Sophia.

Traditionally, the composition of Christ flanked by Mary and John the Baptist (identified by the Greek inscriptions as ‘Mother of God’ and ‘the Forerunner’ respectively) is understood as the moment of final judgement where the believer will petition Mary and John the Baptist for mercy. But the meaning of the Deësis encapsulates the duelling themes in Romans 3 as well.

This iconographic type can be traced at least as far back as the famous sixth-century icon of Christ at Mt Sinai, which illustrates the tension between law and gospel. Christ’s darkened, book-bearing countenance—almost scowling—bears the message of law on his left (Romans 3:20); but the very same face is illumined with a graceful hand of acceptance on the right (Romans 3:21).

In Hagia Sophia’s Deësis, the dynamic to Christ’s left expands to include John the Baptist who illustrates law (Matthew 11:11), and Mary on Christ’s right to indicate gospel (Galatians 4:4). Commenting on Romans 3, the second/third-century theologian Origen connected the law’s inability to fulfil its prescriptions directly to the words of John the Baptist:

Paul establishes rather than terminates the law. When the superior glory of Christ is revealed, that glory brings to an end what had previously appeared and was called glorious. These considerations are reflected in the statement, It is necessary that he increase, and that I decrease (John 3:30) (Patout Burns and Newman 2012: 81).

The resigned countenance of John the Baptist may therefore testify to the law’s accurate but powerless diagnosis of the human condition (Romans 3:23). On the other hand, the gesture of Mary, damaged at Hagia Sophia, would have shown her pointing—as she does in Constantinople’s famous Hodegetria (‘she who shows the way’) icon—away from herself to the cure (Romans 3:24).

References

Cormack, Robin. 2000. Byzantine Art (Oxford: Oxford University Press)

Cutler, Anthony. 1987. ‘Under the Sign of the Deēsis: On the Question of Representativeness in Medieval Art and Literature’, Dumbarton Oaks Papers, 41. Studies on Art and Archeology in Honor of Ernst Kitzinger on His Seventy-Fifth Birthday: 145–154.

Patout Burns, Jr., J., and Father Constantine Newman. 2012. Romans: Interpreted by Early Christian Commentators. The Church’s Bible (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans)

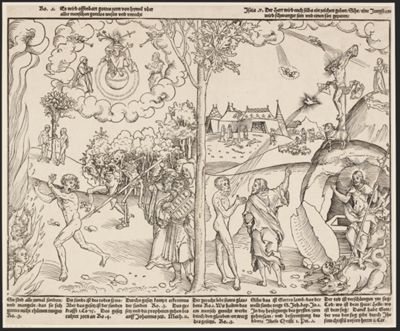

Lucas Cranach the Elder

The Old and the New Testament (Allegory of the Law and the Gospel), c.1530, Woodcut, 270 x 325 mm, The British Museum, London; 1895,0122.285, © The Trustees of the British Museum / Art Resource, NY

Justified by Faith

Commentary by Matthew Milliner

The heat of obligation and the cool of acceptance are contrasting currents that generate an interior storm in human experience.

The third chapter of Romans records the Apostle Paul’s famous division of these mixed dynamics, and in this archetypically Protestant image, Lucas Cranach the Elder (1472–1553) offered the most noteworthy visual attempt to do the same. In both Paul’s letter and Cranach’s art, Jew and Gentile humanity, prodded by the devil and death, are driven by Moses’s tablets into a furious swirl of condemnation (Romans 3:23, 27 is inscribed in the German vernacular in the bottom left of Cranach’s composition). On the right, however, this accusation is silenced by the righteous flow of Christ’s blood that covers the relieved sinner (Romans 3:28 is printed just below the composition-unifying tree).

Working closely with Martin Luther, Cranach began his law and gospel series in 1529, for which he created so many variations that no two panels are completely alike. This particular woodcut version responds to the compressed spatial demands of a portable print, adding a Deësis (John the Baptist and Mary flanking Christ) on the side of law, but also a Virgin Mary on a hilltop on the gospel side, to illustrate grace. John the Baptist is here less prominent than in other versions, turning more of his back to the viewer as if to illustrate his humility: he is not to be the focus of our attention.

Unlike Cranach’s other attempts, the encampment of the brazen serpent (Numbers 21:4–9) has here migrated to the gospel side of the panel, perhaps to illustrate that the distinction between law and gospel is not as simple as the division of the Old and New Testaments. Another surprise is the inclusion of the dove, reminiscent of Luther’s statement, ‘The Law never brings the Holy Spirit; therefore it does not justify, because it only teaches what we ought to do. But the Gospel does bring the Holy Spirit, because it teaches what we ought to receive’ (Pelikan and Lehmann 1955: 208–9).

References

Dillenberger, John. 1999. Images and Relics: Theological Perceptions and Visual Images in Sixteenth-Century Europe (New York: Oxford University Press)

Noble, Bonnie. 2009. Lucas Cranach the Elder: Art and Devotion of the German Reformation (New York: University Press of America)

Pelikan, Jaroslav, and Helmut T. Lehmann (eds.). 1955–1986. Luther’s Works, vol. 26 (St Louis: Concordia)

Rosebrock, Matthew. 2017. ‘The Highest Art: Martin Luther’s Visual Theology in Oratio, Meditatio, Tentatio,’ (unpublished PhD thesis, Fuller Theological Seminary)

Martin Creed :

Work No. 232: the whole world + the work = the whole world, 2000 , Neon lights and metal

Unknown artist :

Deisis/Deësis Composition of Hagia Sophia, 13th century , Mosaic

Lucas Cranach the Elder :

The Old and the New Testament (Allegory of the Law and the Gospel), c.1530 , Woodcut

Camouflage Cranach

Comparative commentary by Matthew Milliner

The third chapter of Romans is less another contribution to a human culture that imagines its own steady advance than an attempt to bring the entire project to a halt.

A potent barrage of scriptural citations is unloaded on Jew and Gentile alike (Romans 3:9–19). Objectors who think they might have kept God’s exacting standards are immediately shushed, and shown to be forgetful of the law’s purpose (Romans 3:20). To speak in terms of the British Museum’s Law and Gospel woodcut by Lucas Cranach the Elder, only when the heat of this message is experienced, does the unexpected ‘chest-splash’ of relief arrive (Romans 3:23–24).

Protests that Paul’s Romans 3 broadside is inapplicable to modern people stop short of a deep investigation of the human condition. Sociologist Alain Ehrenberg (2010) identifies a recent shift from the axis of the permissible (‘should I do it?’) to the axis of the possible (‘can it be done?’), in which the failure to show ourselves both competent and efficient results less in neurosis than depression. This predicament is equally susceptible to Paul’s diagnosis, for the message of grace over works affords a stop button on the treadmill (frequently literal, for fitness-obsessed moderns) of generating our own self-worth.

Like a good sermon, the Hagia Sophia Deësis mosaic, without losing Cranach’s dichotomy between law (Christ’s left, our right) and gospel (Christ’s right, our left), personally draws the believer into the field of Christ’s just and loving gaze. The two images, Cranach’s Law and Gospel and the Byzantine Deësis, work in tandem in bringing Romans 3, which is both universal and personal at once, to the eyes. This comparison affords a visual corollary to the Finnish interpretation of Luther that has identified compatibilities with Eastern Orthodox theology (Braaten and Jenson 1998), even while it subverts Cranach’s own polemical consignment of the Deësis to the left side of the British Museum panel to signify merely law.

But the law and gospel message of Romans 3 can be read not only backward, but forward in time. Annoyed by those who call the Tate Modern a secular cathedral, Andrew Marr demurs: ‘We should be nervous of the simile between art and religion. … Art may “ask questions”, console and delight, but it rarely presumes to offer new ways to live’ (Morris 2010: 15–16). But these ‘code[s] by which to live’ which Marr believes constitute religion are precisely what Romans 3 attempts to terminate, replacing law with liberty and grace.

As if to highlight the very point, Martin Creed’s Work No. 232, ‘the whole world + the work = the whole world’, is an inescapable proclamation that greets elevator-ascending viewers on level 4 of Tate Modern, London. Beneath the neon words, gallery seating urges visitors to contemplate, perhaps, the transience of the cultural accomplishments that fleetingly occupy the massive turbine hall. Work No. 232 may even remind some viewers of the olive branch extended to Protestant understandings of grace in the Catechism of the Catholic Church, where St Thérèse of Lisieux (1873–97) remarks, ‘In the evening of this life, I shall appear before you with empty hands, for I do not ask you, Lord, to count my works’ (CCC, 542).

If this message is absorbed, Tate visitors are invited to cross the nearby bridge to the same museum’s Blavatnik building. Ascending to the tenth-floor viewing room, another of Creed’s neon messages awaits above the elevator: ‘EVERYTHING IS GOING TO BE ALRIGHT’. Referring to this more positive work, Creed remarks: ‘To me it’s optimistic. But to me it also contains the negative, the opposite’ (Martin Creed 2006). Or as Luther put it, ‘You know that God has sent two kinds of preaching into the world, one of the Law, the other of the Gospel. One must have them both…’ (Pelikan and Lehmann 1955: 199, 200).

Creed leaves interpretation of his work militantly open-ended, but if his message is received as consolation, then visitors can return to the art of the galleries below, experiencing them apart from idolatrous expectations of art’s ultimate value. In the same way, the believer justified by faith is still expected by Paul to gratefully perform good works, but without investing such accomplishments with saving significance (Romans 3:31), for salvation belongs to God alone.

Tate Modern itself would thereby become the largest Cranach panel yet, as public an encapsulation of the message of Romans 3 as the pediment that illustrates St Paul’s blinding conversion apart from works on the Cathedral across the Thames.

References

Braaten, Carl E., and Robert W. Jenson (eds.). 1998. Union with Christ: The New Finnish Interpretation of Luther (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans)

Catechism of the Catholic Church. 2003. (New York: Doubleday)

Ehrenberg, Alain. 2010. The Weariness of the Self: Diagnosing the History of Depression in the Contemporary Age (Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press)

Morris, Frances. 2010. Tate Modern: The Handbook (London: Tate Publishing)

Pelikan, Jaroslav, and Helmut T. Lehmann (eds.). 1955–1986. Luther’s Works, vol. 58 (St Louis: Concordia)

TheEYE: Martin Creed. 2006. (Illuminations media)

Commentaries by Matthew Milliner