Numbers 21:1–9

The Bronze Serpent

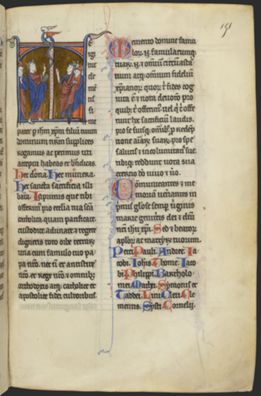

Unknown artist

The Bronze Serpent, from a Latin Missal, 1075–1125, Illuminated manuscript, 310 x 205 mm, Biliothèque nationale de France, Paris; Latin 12054, Bibliothèque nationale de France

A Serpent with Wings

Commentary by Mark Scarlata

This eleventh-century French illumination of Moses and the bronze serpent reveals how often our visual imaginations influence our reading of the Bible. As we look to the serpent on top of the pole, we would not be mistaken in interpreting the artist’s work as some sort of dragon. Did the artist misunderstand the biblical story? Yet a brief look into serpent iconography reveals that the most common images of snakes in the ancient world were depicted with two or more wings.

In the ancient near East, serpents were considered magical winged creatures that contained extraordinary power. Egypt was the home of serpent images, charms, and iconography. On the throne of Tutankhamen, we find two wings of a four-winged snake projecting outward from the back of the seat as if flanking and protecting the king on both sides. The erect, coiled cobra was the symbol of Egyptian royalty and we recall Moses’s own confrontation with the magicians of Egypt when their staffs turned into serpents and Aaron’s staff devoured them all (Exodus 7:9–12).

The bronze serpent is elevated centrally in the illumination as if we, like the Israelites, are called to fix our gaze upward upon it. It even protrudes beyond the confines of the frame, suggesting a continuity with our own space and time. Moses stands below with one finger pointed toward the serpent, guiding us to look, whilst his other hand holds the Torah scroll. We note that he is depicted with horns, showing the influence of Jerome’s Latin translation of Moses’s shining face in Exodus 34:29. Jerome rendered the Hebrew qaran (‘shine’) with cornuta (‘horned’), an interpretation whose artistic effects extend all the way to Michelangelo’s sculpture of Moses in San Pietro in Vincoli, Rome.

To the right of Moses are two men with rosy cheeks, slightly smiling as they obediently look up to the serpent and experience healing. On the left of Moses stands a single man who glares at the prophet with hand outstretched, refusing to cast his glance at the bronze image. He represents those who have rejected God and Moses outright and will die in the wilderness.

Giovanni Fantoni

The Brazen Serpent Monument, 20th century, Bronze, Mount Nebo (Khirbet as-Sayagha), Jordan; Dmitrii Melnikov / Alamy Stock Photo

A Serpent on Mount Nebo

Commentary by Mark Scarlata

Giovanni Fantoni's sculpture is located on the traditional site of Moses’s death overlooking the Promised Land. At first it appears to be a cross, but upon closer inspection we see a tubular-like serpent with a cobra head wrapped around a pole. This, however, is no ordinary pole as the artist has crafted it from small, individual tubes that extend to its base reflecting the same fluid, serpentine feel. The wings of the serpent are outstretched and emerge from the pole itself. Though separate elements, the pole and serpent are bound together as one.

In the biblical story, God commands Moses to make a saraph, or a fiery serpent, and place it on a pole (Numbers 21:8) but does not specify what material to use. The choice of bronze (or possibly copper) relates to the sounds of the Hebrew words for snake (nahash) and bronze (nehoshet). The wordplay emphasizes the connection between the material and what is crafted which also influences the name later associated with the object, Nehushtan (2 Kings 18:4).

We find a similar importance in the materials chosen by Fantoni. This is no burnished bronze, gleaming brightly in the Middle Eastern sun. Instead, it is burnt, rusted, and oxidized by the relentless elements of the desert. The russet-coloured patina evokes a sense of the physical and spiritual dryness of the wilderness wanderings and may remind us of the suffering of Christ on the cross who in the barrenness of the crucifixion proclaims, ‘I am thirsty’ (John 19:28).

The cruciform motif is Fantoni’s visual interpretation of Christ’s words in John 3:14: ‘And just as Moses lifted up the serpent in the wilderness, so must the Son of Man be lifted up’. The artist has carefully blended the sign of the bronze serpent and the healing it symbolizes with the cross of Christ. The two symbols, cross and serpent, here brought together as one, offer a visual reminder of the unity Christians find within the whole of Scripture.

Unknown Ethiopian artist

Processional Cross, 16th century, Bronze, 47 x 35 x 3 cm, The British Museum, London; Previous owner/ex-collection: Sir Richard Rivington Holmes, Af1868,1001.16, ©️ The Trustees of the British Museum

Lifting Our Eyes to the Cross

Commentary by Mark Scarlata

This sixteenth-century Ethiopian processional cross combines the motifs of Moses’s bronze serpent with the crucifixion, resurrection, and ascension of Christ. Cast in bronze, the cross bears a subtle glow, but when fully polished it would gleam brightly in the light.

The large central cross frames an intricately patterned area made up of small interlaced cross motifs. By contrast, the crosses that protrude upwards and to left and right of the central cross, as well as the curved design at its base, incorporate serpentine curls. Though there is no figurative depiction of a serpent here, nevertheless these abstract forms draw our imaginations to Moses’s serpent in the wilderness and the healing it provided.

Though currently housed in the British Museum, this cross was designed for liturgical purposes. The procession of the cross towards the altar at the beginning of the eucharistic liturgy is a sign of Christ’s presence entering the church. Worshippers cast their glance upward to recognize and acknowledge the healing power of Christ who was once lifted up on the cross. This liturgical ritual is a reminder of Christ’s victory over death and the healing and restoration he brings to all creation.

The Israelites, too, may have lifted their eyes to the bronze serpent during worship. In later religious reforms under king Hezekiah, Moses’s bronze serpent (Nehushtan) was destroyed (2 Kings 18:4). It is probable that the religious artifact was erected in the Temple courtyard where daily sacrifices were made. The proximity of the icon to the altar may have led the Israelites to believe they were offering sacrifices to the serpent rather than to YHWH and thus to confuse their true source of healing.

The prophets were also aware of the healing traditions associated with the bronze serpent. According to Isaiah (14:29; 30:6), a seraph was a flying serpent, and it becomes the agent of healing and purification in his Temple vision (Isaiah 6:5–7; Levine 2000: 87). This offers a link to the winged, healing serpent of Moses which the artist alludes to in the Ethiopian processional cross, recalling Christ’s gift of healing to the world.

References

Levine, Baruch. 2000. Numbers 21–36 (New York: Doubleday)

Unknown artist :

The Bronze Serpent, from a Latin Missal, 1075–1125 , Illuminated manuscript

Giovanni Fantoni :

The Brazen Serpent Monument, 20th century , Bronze

Unknown Ethiopian artist :

Processional Cross, 16th century , Bronze

From Rejection to Healing

Comparative commentary by Mark Scarlata

This is the final episode of Israelite complaint in the Sinai wilderness—a series of grumblings that began soon after their exodus from Egypt. Not only is this the last account of the people’s contention with God, but it is also the most grievous. They utterly reject YHWH’s authority and their anger is directed ‘against God and against Moses’ (Numbers 21:5). As a result, God sends serpents among them; then (after they repent) provides them with a means of healing. They can be preserved from the serpents’ venom by looking upon a bronze serpent that Moses fashions.

The French illumination in this exhibition opens our imaginations to see familiar biblical texts in a new light. Contemporary viewers may not often mentally picture serpents with wings and yet the representation of just such a serpent on this pole allows for a different nuance in our interpretation. The wings may have been a sign of protection as they were on Pharaoh’s throne. Other winged serpents from ancient Egypt appeared on amulets which were used for healing and preserving one from serpent attacks (Milgrom 1989: 459). Isaiah sees seraphs (or angelic figures with serpent shapes) with wings in the Temple, and these also bring healing. This illumination reminds us of the importance of understanding Scripture in its ancient context. Such contextualization can reveal additional associations which, as in this case, allow Christian readers to make links with Christ.

Giovanni Fantoni’s sculpture invites us, as Jesus himself does in John’s Gospel, to see further layers of meaning in the signs given by God to Moses as they are filled out in Christ. The blending of the serpent’s shape with the cross visually invites us to a Christian understanding of Scripture as a narrative that is intimately bound together through the Old and New Testaments. From this perspective, the story can be read as God’s healing of the Israelites from the fiery serpents, but it also points to the consummation of all healing as understood through the atoning sacrifice of Christ. God healed Israel from the sting of serpents; Christians find in that a symbolic foreshadowing of Christ’s healing from the venom of the serpent in Eden. The death that came through the first Adam was redeemed by the second Adam who was lifted high upon the cross (1 Corinthians 15:20–22). And the extended wings of Fantoni’s sculpture can remind us of the extended hands of Christ, nailed to the cross, that will bring healing to all nations and to all of creation.

As the Christian Church has gathered in worship in the centuries after Christ’s resurrection and ascension, it has looked to the cross as a sign of victory and healing from sin and death. As liturgical rituals developed, the processional cross became a symbol of Christ’s presence among the worshipping community. Unlike many Western depictions of the cross, the fluid, serpentine Ethiopian cross conjures up memories of Moses’s bronze serpent in the wilderness and the words of Christ who identifies himself with the Old Testament symbol.

Meditating on all three works, we find motifs of healing that are represented in visual signs. The winged bronze serpent on a pole alludes to Egyptian traditions that were taken on by the Israelites and later used by the prophets. The sign of the cross became the central symbol of Christ’s crucifixion that brought about the healing of all creation.

Whether outstretched wings high on a pole or outstretched hands nailed to a cross, these works of art help us in seeing and understanding the crucial bonds between the signs given in both Old and New Testaments. God’s grace of healing among the Israelites who rejected him in the wilderness was seen again through the rejection of the Son who, like Moses’s bronze serpent on a pole, was lifted up on the cross.

References

Levine, Baruch. 2000. Numbers 21–36 (New York: Doubleday)

Milgrom, Jacob. 1989. Numbers (New York: Jewish Publication Society)

Commentaries by Mark Scarlata