Numbers 22:1–35

Balaam and the Ass

Rudolf von Ems

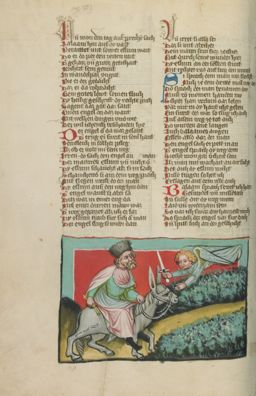

Balaam's Ass, from the Weltchronik, about 1400–10, Tempera colours, gold, silver paint, and ink, 33.5 x 23.5 cm, J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles; Ms. 33 (88.MP.70), fol. 105v, Digital image courtesy of the Getty's Open Content Program

What’s in Front of Your Nose

Commentary by Bridget Nichols

This image appears in an illustrated Weltchronik, probably produced in Regensburg, Bavaria, between 1400 and 1410, with a further addition in 1487. It is one of a number of manuscript versions of the Austrian poet Rudolf von Ems’s (c.1200–c.54) compilation of salvific events in world history.

Balaam’s inclusion in a history of salvation points to a positive appreciation on the poet’s part, despite the judgement of the biblical record that Balaam was a bad prophet. We might conclude that Rudolf was looking to Numbers 24:17, where Balaam prophesies that ‘a star shall come out of Jacob, and a sceptre shall rise out of Israel’. Christian tradition took this up as a messianic reference and associated it typologically with the star observed by the Magi.

The artist has shown only the three central figures in the episode—Balaam, the ass, and the angel—and the illustrator subverts the prophet’s dignity in several ways. The viewer is drawn immediately to the fierce intentness of the gazes of prophet, ass, and angel. But while the ass trains her eyes on the angel, and the angel looks directly at Balaam, Balaam’s angle of vision is oblique and suggests that he is not seeing what the ass sees.

Their difference of vision is counterbalanced by the physical similarities that link prophet and creature. The coarse fur of Balaam’s hat is picked out in vertical brush strokes, replicating the hairy ears and straight forelock of the ass. While Jewish men were usually shown by medieval artists wearing round hats tapering to a high point, Polish and Lithuanian Jews were not subjected to the strict identifying dress codes operating in other parts of Europe. Has the Austro-German artist chosen to suggest both Jewish identity and foreignness in this way, consistent with the biblical Balaam who obeys the God of Israel, yet lives far away from the Israelite people?

The angel is caught in flight over the path between schematically painted vineyards. His sword blade points upward, menacingly close to Balaam, but his left hand seems to stretch almost tenderly towards the ass. Perhaps the angel has understood her fear and indignation and is poised to console her by stroking her muzzle.

References

Aust, Cornelia. 2019. ‘From Noble Dress to Jewish Attire: Jewish Appearances in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth and the Holy Roman Empire’, in Dress and Cultural Difference in Early Modern Europe, ed. by Cornelia Aust, Denise Klein, and Thomas Weller (Berlin: De Gruyter Oldenbourg), pp. 90–112

Getty. n.d. ‘MS 33 (88.MP.70)’, available at https://www.getty.edu/art/collection/object/103RWQ [accessed 22 July 2024]

Rowe, Nina. 2018. ‘Devotion and Dissent in Late Medieval World Chronicles’, Art History, 41.1: 12–41

[Charles Blakeman window in St Etheldreda’s, Ely Place (1953-1958) depicts the Magi and the angel, with Balaam and the ass in the far left. The star is placed centrally over the angel’s head: https://loandbeholdbible.com/2017/08/19/balaam-foresees-a-star-numbers-221-2425/ ]

Rembrandt van Rijn

Balaam and the Donkey, 1626, Oil on panel, 63 x 46.5 cm, Musée Cognacq-Jay, Paris; J 95, Album / Art Resource, NY

Balaam in Bedlam

Commentary by Bridget Nichols

Rembrandt van Rijn produced his painting of Balaam and the Angel in 1626, four years after his teacher Peter Lastman had addressed the same subject.

Rembrandt introduced a dynamism into his composition that was lacking in Lastman’s by organising all the figures as players in a real-time drama. The angel moves from the right of the canvas to the left, and stands behind the prophet, his sword about to descend. The Moabite representatives move from a distant position to participate in the action. Balaam’s two young servants stand as shadowy presences between them and Balaam on the ass.

Rembrandt’s treatment has elements of sheer comic hyperbole—in Bruce Bernard’s words, ‘the extrovert miller’s son amusing himself’ (Bernard 1988: 282). He has exploited the motif of sight to the full: the professional seer does not see the angel, yet the female animal does, as her wide-open eyes bear witness. Balaam’s eyes, by contrast, are small dark cavities.

What the Moabites and the servants see is cause for embarrassment and consternation. The man who has set out in expensive clothing made of rich fabrics and trimmed with fur is suddenly flailing about on the back of a collapsed donkey, having lost a shoe. Dressed in sober colours, the three turbaned Moabites behind him, one mounted on a well-bred horse and appearing to look down his nose, are eloquent simply by their presence. Should they be surprised? The leather satchel, bulging with papers and a wooden staff, has all the signs that any available aids to divination have been hastily stuffed into it.

The angel is a commanding presence almost against the odds. His muscular build is flimsily covered by a precariously attached white garment and he wears exaggerated wings suggestive of a great bird of prey. The ass is captured in the act of speech, fearful of the blow about to descend on her, yet defiant. The detail of her furry ears and the ruff running the length of her throat perhaps nods to the fur trim on Balaam’s sleeve.

Who speaks and sees truly in this story of a prophet?

References

Bernard, Bruce. 1988. The Bible and Its Painters (London & Sydney: Mcdonald Orbis)

Rudolf von Ems :

Balaam's Ass, from the Weltchronik, about 1400–10 , Tempera colours, gold, silver paint, and ink

Gladwyn K. Bush (Miss Lassie) :

Balaam and the Ass, 1995 , Oil on canvas

Rembrandt van Rijn :

Balaam and the Donkey, 1626 , Oil on panel

Beatings, Blessings, and Blame

Comparative commentary by Bridget Nichols

The story of the non-Israelite prophet and seer Balaam, and his response to the summons of Balak the Moabite ruler to curse the Israelite people, occupies three chapters in Numbers. Initially, God refuses to let Balaam go to Moab or to curse God’s people. Balaam’s reluctant agreement to undertake the mission after a second party of emissaries is sent from Balak is sanctioned by God. But God then appears to undergo a further change of heart and becomes angry (Numbers 22:22).

The high point in the narrative comes when Balaam’s she-ass (the Hebrew text is specific) finds her voice. As they travel, she sees an angel barring the road. Three times, the angel obstructs progress and Balaam, who does not see the angel, beats her angrily. When God gives her the power to speak, she protests that she has carried Balaam faithfully and does not deserve ill-treatment. Balaam now perceives the angel. When Balaam arrives in the Moabite territory, instead of cursing the Israelites, he assures them of God’s blessing.

Animals and birds who address human beings in their own language are well represented in world literature. Yet in biblical literature, only the serpent in the Garden of Eden and the eagle who cries ‘Woe to the earth’ in Revelation are possible companions to the ass (Genesis 3:1–7; Revelation 8:13).

Balaam not only replies to the ass’s rebuke, but does so as if he is quite accustomed to having conversations with her. Gender matters here almost as much as species. It would have been unseemly for a woman to remonstrate with a prophet. An eloquent female animal adds a further element of mockery to an already ridiculous situation.

Despite proving himself to be on Israel’s side, Balaam’s subsequent career is dark. He is held responsible for the seduction of Israelite men by Midianite or Moabite women (Numbers 25; 31:8) and finally put to death (Numbers 31:8; Joshua 13:22). In Micah 6:5, 2 Peter 2:15, Jude 1:11, and Revelation 2:14, he becomes an example of someone who led God’s people astray and dabbled in divination for money. The fifth-century CE collection of rabbinic writings known as the Babylonian Talmud alleges that that he had a sexual relationship with the ass (Sanhedrin 105b).

The three responses to the encounter with the angel by Rembrandt van Rijn, the illustrator of the Weltchronik, and Miss Lassie all recognize its drama, while emphasizing different aspects of the episode. In Rembrandt’s exuberant scene, the seer’s failure to see is given comic treatment, exaggerated by skilful contrasts in the depiction of eyes and lines of sight. Likewise, his humiliation before sombre observers is heightened when he is seen opulently dressed astride a kneeling animal, and missing a shoe. The hastily packed satchel points to someone who has set out in a great hurry.

The Weltchronik illustrator has reduced the cast to Balaam, the ass, and the angel in a visual counterpart to the text. But the artist has found ways, especially brush techniques, of mischievously suggesting similarities between the prophet and the ass. The angel mediates between them, directing the sword at Balaam, but stretching out what could be read as a reassuring hand to the ass. Eyes play an important part, as they do in Rembrandt’s treatment.

Miss Lassie’s interpretation could be enjoyed simply for its vivid use of colour, its ostentatious labelling of the scene, and its double signature—as if to make sure that there should be no mistake about attribution. It merits closer inspection, particularly of the ass. Whereas the angelic and human figure are relatively static, the ass is addressing the angel vehemently. Balaam has ceased to matter and his half-hearted beating is ignored.

The further unfolding of events following the meeting with the angel in Numbers, and references to Balaam in later biblical tradition, neither found him amusing, nor considered the ass to be of interest (except in the Talmudic allegation of bestiality, which was part of a wider presentation of Balaam as a bad prophet).

The three artists represented here have shown that serious themes can be illuminated by attention to incongruous and often diverting detail.

References

Alter, Robert. 2004. ‘Balaam and the Ass: An Excerpt from a New Translation of the “Five Books of Moses”’, The Kenyon Review, 26.4: 6–32

Berkowitz, Beth A. 2018. Animals and Animality in the Babylonian Talmud (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press)

Van Kooten, George H. and Jacques van Ruiten (eds). 2008. The Prestige of the Pagan Prophet Balaam in Judaism, Early Christianity, and Islam (Leiden: Brill)

Commentaries by Bridget Nichols