Psalm 90

Handwork

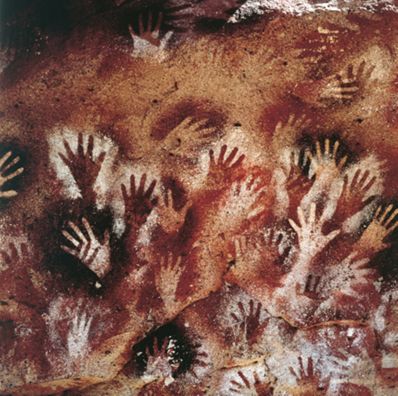

Unknown artists

Cueva de las Manos (Cave of Hands), began c.7,000 BCE, Mural, UNESCO Wolrd Heritage Site, Santa Cruz, Argentina; De Agostini Picture Library / Bridgeman Images

A Dwelling Place for All Generations

Commentary by Rachel Muers

The hand paintings in the Cueva de las Manos reach out to us across more than nine thousand years. Most of the shapes are stencilled; the hand is pressed against the rock and paint is sprayed over it, leaving the image of the hand when it is lifted away. It is a technique found across the world and down the ages. Part of the impact of the Cueva de las Manos comes from the combination of its evident age and its instant recognisability. A thousand years become like yesterday (Psalm 90:4). We can imagine pressing our own hands against the rock, fitting them into the stencilled images, making ‘contact’ with distant ancestors whose forms we still recognize; this was made by people like us.

One theory about the origin of the cave’s hand paintings is that they were created as part of an initiation ceremony for young men entering adulthood (Bradshaw Foundation n.d.). The young man places his hand somewhere near where his father and grandfather placed theirs, overlaying the marks of ancestors; he knows that the rock outlasts all of them, he knows that life is short and he returns to the dust. The painting takes shape; the tentative work of individual hands becomes a dwelling place for generations.

Amid the constant reminders of how short their lives are—compared with the endurance of their rock-built dwelling places—the people of the Cueva de las Manos reach out to create, to represent, to find meaning and shape for their lives. The creation of the hand paintings points to the ability to ask about what was ‘before the mountains were brought forth’ (Psalm 90:2 NRSV)—and to the fleetingness of the life of each person who asks the question.

We fit our hands to the rock paintings and our mouths to the words of the psalms, with a similar shock of recognition—recognizing and reappropriating, not only the touch of a fellow human being, but the imprint of that human being’s encounter with eternity in time.

References

Bradshaw Foundation (South American Rock Art Archive). n.d. ‘Cueva de las Manos’–The Cave of the Hands’, available at http://www.bradshawfoundation.com/south_america/cueva_de_los_manos/index.php

Mitzi Cunliffe

Man-Made Fibres, 1954–56, Portland stone, University of Leeds; LEEUA 1956.013, © Mitzi Cunliffe; Photo University of Leeds Art Collection / https://explore.library.leeds.ac.uk/special-collections-explore/504

Cat’s-Cradle

Commentary by Rachel Muers

Mitzi Cunliffe’s sculpture Man-Made Fibres, unveiled in 1956, was created to celebrate the textile industry that is integral both to the wealth of the UK city of Leeds and to the origins of the University of Leeds, where the work adorns the Clothworkers’ South Building. At first glance, the sculpture’s title suggests a Promethean celebration of technological power, the power of ‘man’ to order and ‘make’ a world. However, the relationship between the hands and the fibres—the hands gently encircling the woven textile yet, conspicuously, made of the same stuff; both hands and handiwork exposed to the elements—suggests, rather, a conscious recognition of the partiality, provisionality, and penultimacy both of the makers and of what they make.

We see in Man-Made Fibres a tribute to the hard work of weaving together institutions, frameworks of meaning, artistic projects—and the joyful willingness to be devoted to the task of making one particular, temporary, contextual thing as good as it can be. Cunliffe famously said that she intended her sculptures to be ‘used, rained on, leaned against and taken for granted’ (Forster 2016)—to be useful, and used, in sustaining a common life beyond the maker’s control.

Prosper the work of our hands for us, says the psalmist in the first part of the double prayer that ends Psalm 90. The work our hands do does not stop being our work; we remain tangled up with it and it with us, we are invested and implicated in it, we take some of the credit and some of the responsibility. The work—the work of art, the text, the institution—remains ‘man-made’, sourced from a particular time and place, resonant of its cultural context.

The prayer continues, however: ‘prosper the work of our hands’. In Man-Made Fibres, the work is a cat’s cradle, held out for someone else to take over, offered forwards to be used at the same time as it is offered up in celebration. There is a promise that comes with provisionality and temporal limitation—the promise that our limitations, our particular desires and imaginings, or even our disastrous failures as yet unrecognized, do not circumscribe the future of the ‘work of our hands’.

References

Cunliffe, Mitzi. 1968. ‘Sculpture, Uniqueness and Multiplicity’, Leonardo, 4.1: 419–22

Forster, Jilly. 2016. ‘Review: The Sculptor Behind the Mask, 3 May 2016’, www.thestateofthearts.co.uk [accessed 12 November 2020]

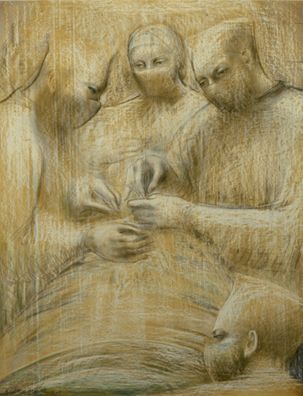

Barbara Hepworth

Concentration of Hands I, 1948, Pencil and oil on plywood, 53.5 x 40 cm, The British Council; P53, Barbara Hepworth © Bowness; Photo: © The British Council, Courtesy of the British Council Collection

The Healer’s Art

Commentary by Rachel Muers

Barbara Hepworth’s hospital drawings are a carefully-observed homage to the ‘craft’ of surgery. The drawings present her vision of the surgeons as followers of a vocation, connected to the artist’s vocation—‘to restore and to maintain the beauty and grace of the human mind and body’ (2013 [1953]). They also coincide with a pivotal moment in British medical history: the creation of a national publicly-funded health service (the NHS).

Commentators on the drawings often note how much they resemble the great religious paintings of the Renaissance (Launer 2016: 367). Hepworth responds to the profound seriousness, the shared encounter with mystery, in the everyday work of the operating theatre. The grouped figures’ reverence is suggested not only by their bowed heads, but also in the intense work of their hands, at the centre of this and many of the other hospital drawings. The surgeon’s work is his or her ‘concentration’. The face of the patient does not appear, but it is hard to tell where the bodies of the surgeons end and the body of the patient begins. Even at the point where there is the greatest imbalance of agency and power, the patient’s life in the surgeons’ hands, we are reminded of their shared embodiment, and hence of their shared vulnerability. We are—including Hepworth, the observer who identifies with the surgeons and recalls her own young daughter’s recent major surgery—all in this together.

As I write these commentaries under Covid-19 lockdown, Barbara Hepworth’s hospital drawings have acquired new poignancy and urgency. The presence of the surgeons’ masks—which in 2020 have come to signify their, not the patient’s, need for protection—draws our thoughts, not only to the fragility of the individual body under the surgeons’ knives, but also to a societal crisis in which the sense of being overwhelmed and consumed (Psalm 90:7) and of crying ‘how long?’ (v.13) is pervasive.

Concentration of Hands engages the crisis at its heart, and concentrates attention on active compassion and hope for healing. It bespeaks the compassion for which the psalmist cries out, divine compassion mediated in the ordinary actions of vulnerable hands that exercise the ‘sharp compassion of the healer’s art’ (Eliot, ‘East Coker’ IV).

References

Eliot, T. S. 1940. ‘East Coker’ (London: Faber & Faber)

Hepworth, Barbara. 2013 [1953]. ‘Sculpture and the Scalpel’, Tate Etc., 27: 13

Launer, John. 2016. ‘The Hospital Drawings of Barbara Hepworth’, Postgraduate Medical Journal, 92: 367–68

Unknown artists :

Cueva de las Manos (Cave of Hands), began c.7,000 BCE , Mural

Mitzi Cunliffe :

Man-Made Fibres, 1954–56 , Portland stone

Barbara Hepworth :

Concentration of Hands I, 1948 , Pencil and oil on plywood

Handling Our Fragility, Seeking a Wise Heart

Comparative commentary by Rachel Muers

Psalm 90 is often described as a psalm of communal lament (Clifford 2004: 191; Goldingay 2008: 21). It is a shout for help arising from a specific moment of collective crisis, the imminent or present collapse of life as it is known—a crisis experienced as the consequence of past actions (figured as divine punishment) but now a crisis in the face of which the community is powerless.

Often, also, and sometimes by contrast, this psalm is categorized as a meditation on wisdom, recalling timeless truths about the fleeting character of human life that everyone in every age would do well to learn; we do not need, or should not need, to be in the middle of a crisis to learn to number our days. The images of hands, and the work of hands, suggest how these two aspects of the psalm—the communal lament and the individual wisdom meditation—come together.

The wall of the Cueva de las Manos speaks about each and every human life, every person across nine thousand years or more who might reach out and touch the wall—he or she flourishes and then fades like grass (Psalm 90:7); and it reflects a specific community’s project and vision, an attempt to structure meaningful lives in a stable dwelling place. Barbara Hepworth’s Concentration of Hands has at its centre an individual human life and its frailty, the body under the surgeon’s knife; but it depicts an intimately shared activity, a tradition of wisdom and skill honed over generations. Created at the time of the founding of Britain’s national health service, Hepworth’s picture also reflects a social and institutional vision that sees human fragility and suffering not as a burden to be borne alone fatalistically but as a shared predicament that calls forth compassion and creativity.

The hands that reach out to heal, create, or build, as well as the institutions and the cultures they create, are all made of the same creaturely stuff that withers and fades, that may be consumed or overwhelmed by disaster. Mitzi Cunliffe’s strong hands are exposed to the elements and merging with the fibres they weave; Hepworth’s surgeons wear their flimsy masks. The wisdom meditation—all life is fleeting—points inexorably towards the communal lament. In turn, however, the communal lament points back towards the urgent search for wisdom—for some indication of how to ‘restore and to maintain the beauty and grace’ (Hepworth 2013 [1953]), not only of the individual body but also of the social body.

From the middle of its communal lament—its cry of ‘how long?’ (v.13)—and in the face of overwhelming destruction, Psalm 90 grasps at the possibility of remaking the individual’s heart and the community’s life. It reaches for God’s faithfulness (v.14) as the hand reaches for the solid rock that has been a dwelling place for generations, leaned upon and taken for granted. It calls on the God who ‘turns’ people to dust, to turn towards God’s people and restore their common life (v.3)—reworking and restoring it with infinite compassion, from the heart outwards, like the transformation occurring under the concentrated hands of the surgeons.

What is particularly striking in Psalm 90 is that what sounds like the resounding finale to a communal drama—the reversal of fortune, affliction repaid with gladness, the glorious power of God made manifest—is not in fact the ending. The final double prayer for the ‘work of our hands’ recalls us to the quotidian; the vocations and traditions and institutions that these works of art celebrate as the ‘work of our hands’:

Prosper for us the work of our hands—

O prosper the work of our hands! (v.17 NRSV)

Specifically, the intergenerational community is the context in which wisdom is learned and passed on, hand to hand—like the cat’s-cradle in Cunliffe’s sculpture—to be used and remade; we and our work are given over into each other’s hands.

Psalm 90 begins with a reference to ‘all generations’ (v.1) but ends with the more specific and precarious reference to ‘children’ (v.16). The collective future before God, the future compassionately granted in God’s ‘turning’, is not an indefinite open-ended continuum of more of the same, but rather a repeated call to take up, perform, and pass on the work of our hands.

References

Clifford, Richard J. 2004. ‘Psalm 90: Wisdom Meditation or Communal Lament?’, in The Book of Psalms, ed. by Patrick D. Miller and Peter W. Flint (Leiden: Brill), pp. 190–205

Goldingay, John. 2008. Psalms 90–150 (Grand Rapids: Baker Academic)

Hepworth, Barbara. 2013 [1953]. ‘Sculpture and the Scalpel’, Tate Etc., 27: 13

Commentaries by Rachel Muers