Daniel 4

Back from the Brink

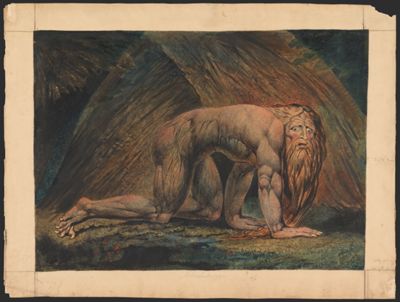

William Blake

Nebuchadnezzar, 1795–c.1805, Colour print, ink, and watercolour on paper, 543 x 725 mm, Tate; Presented by W. Graham Robertson 1939, N05059, Photo: © Tate, London / Art Resource, NY

The Balance of Powers

Commentary by Jonathan Evens

William Blake viewed his artistic practice as a form of opposition to various kinds of domination, and the repressive and oppressive effects of power (Davis 1977: 43).

If ever there was a story of domination it is the story of Nebuchadnezzar, whose greatness reached to heaven and his sovereignty to the ends of the earth (Daniel 4:22). Yet Blake’s interest in and depiction of this oligarch is not of his dominance, but his humiliation.

Despite Blake’s initial enthusiasm for the French Revolution, his opposition to the dominant forces of his own day was not primarily political. He had a spiritual aim in mind, one of cleansing the ‘doors of perception’ so that the material world (with its sensuality and rationality) could be seen, through imagination, as it ultimately is—infinite (Blake 1979: 188).

To achieve this aim, Blake believed it was necessary to creatively balance the complementary opposites within human beings and societies. This is the ‘Marriage of Heaven and Hell’ about which he wrote. His belief in this balance was the ultimate impetus for his opposition to domineering forces, including the dominance of sensuality and reason, which were so antipathetic to imagination.

It is the dominance of sensuality that Blake depicts in his hand-coloured print, Nebuchadnezzar. He based Nebuchadnezzar’s pose on Albrecht Dürer’s late fifteenth-century woodcut showing the medieval legend of the penance of St John Chrysostom. According to that story, the saint had himself succumbed to carnal and sensual temptation, and his chosen penance mirrored the degradation of Nebuchadnezzar (Wind 1937: 183). Blake likewise shows a human being who—by becoming a slave to sensuality—has reverted to the bestial: he is naked and on all fours with hair like feathers and nails like claws.

Nebuchadnezzar was part of Blake’s Twelve Large Colour Prints series in which, rather than there being an overarching narrative, the images seem to be linked by being paired with one another. His Nebuchadnezzar was paired with a Newton who represented the dominance of reason in eighteenth-century society, with its rational, scientific explanations for the world. Blake believed that both the rationalism and the sensuality he depicted in these two images repress the imagination.

They serve as warnings which aim to open the doors of our perception.

References

Blake, William. 1979. The Marriage of Heaven and Hell in The Complete Poems (Harmondsworth: Penguin Books)

Butlin, Martin. 1990. William Blake 1757–1827 (London: Tate Gallery Publications)

Davis, Michael Justin. 1977. William Blake: A New Kind of Man (London: Elek)

Wind, Edgar. 1937. ‘The Saint as Monster’, Journal of the Warburg Institute 1.2: 183

Arthur Boyd

Nebuchadnezzar's Dream of the Tree, 1969, Oil on canvas, 174.5 x 183 cm, National Gallery of Australia, Canberra; The Arthur Boyd gift, 1975, NGA 1975.3.95, Photo: National Gallery of Australia, Canberra

The Ground of Rebirth

Commentary by Jonathan Evens

William Blake’s Nebuchadnezzar was the initial inspiration for Australian artist Arthur Boyd’s series of Nebuchadnezzar paintings. Boyd viewed Nebuchadnezzar’s weakness as being his desire ‘to possess everything’ (Bungey 2000: 434). This may have reflected a degree of self-awareness in Boyd, for whom this series became an obsession as he sourced all the information he could on Nebuchadnezzar and ‘tore into the paint with a fury, his hands over the canvas like a concert pianist deprived too long of his grand piano’ (Bungey 2000: 426).

Nebuchadnezzar’s Dream of the Tree is a calm work within this wild series. If Boyd’s expressionistic use of paint across the more than seventy paintings in the series mirrors the violence with which Nebuchadnezzar’s reason unravels, then this particular work modulates into a different emotional key as his reason returns.

In the biblical text, Nebuchadnezzar’s dream of a tree was the catalyst for his eventual descent into distress (Daniel 4:10–17). Daniel interpreted the Great Tree in the king’s dream as Nebuchadnezzar himself. Having grown too great in power and pride, he was to be driven away from people to live with the wild animals (Daniel 4:20–27).

By setting the vision of the tree in the outback, however, Boyd relocates the dream to a point in the story after Nebuchadnezzar’s banishment to the wilderness, at the end of his distress. Nebuchadnezzar is shown as a semi-translucent, recumbent figure from whose groin the tree grows until it touches the line of the horizon. When, in his pride, Nebuchadnezzar created an image of gold, he required others to abase themselves on the ground before the image standing above them. Here, however, in a sign of new-found humility, it is Nebuchadnezzar himself who is on the ground. No longer in a position of dominance, he is the soil from which new life is growing.

The king is now ready to return to the seat of power with a new-found humility, giving a fertility and fruitfulness to the latter part of his reign. Australian musician Chris Latham, who directed Invocations: Eight meditations on paintings by Arthur Boyd at the National Gallery of Australia in 2014, notes that here ‘we have the archetypal “tree of life” growing out of Nebuchadnezzar's decrepit form, a deeply moving image of renewal, replenishment and rebirth’ (2014).

References

Bungey, Darleen. 2000. Arthur Boyd: A Life (Sydney: Allen & Unwin)

Latham, Chris. 2014. ‘Chris Latham's Invocations puts Arthur Boyd's National Gallery paintings to music, 24 October 2014’, www.smh.com.au [accessed 5 July 2019]

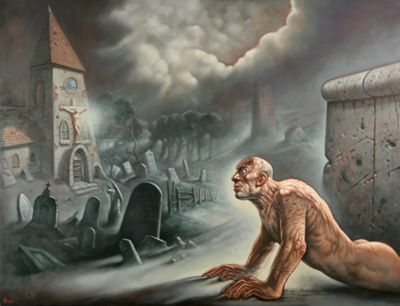

Peter Howson

The Third Step, 2001, Oil on canvas, 189 x 259 cm, Flowers Gallery; AFG 33212, © Peter Howson, courtesy of Flowers Gallery

Into the Zone of Brightness

Commentary by Jonathan Evens

In The Third Step, Peter Howson depicts a naked man dragging himself along the ground in a church graveyard. In the context of this virtual exhibition, Howson’s crawling figure can evoke Nebuchadnezzar in his distress because—to echo King Lear’s remark about the naked Edgar—the artist has here shown us a ‘poor, bare, forked animal’ (King Lear 3.4.105–7). The man has been brought low having lost the accoutrements of civilization, and is looking up from his position among the gravestones towards the illuminated crucifix on the church tower.

Conversations with Howson have revealed that the artist identifies with this figure because, after being strung out on drugs and alcohol, he himself ‘finally recognized he had reached rock bottom and entered the addiction treatment centre at Castle Craig Hospital in the Scottish Borders’ (Kohan 2012: 76). While he was ‘following the twelve-step recovery program of Alcoholics Anonymous he sensed the presence of Christ in his room one night, telling him he was loved and would be cured’. He had the same experience every night for the next three months. ‘Redemption had come to him in his private hell’ (Kohan 2012: 76). Howson’s minister, the Reverend Peter White, confirms that The Third Step ‘reflects [the artist’s] own recovery from his difficulties, made possible by his discovery of the love of Jesus’ (Fraser 2002).

John A. Kohan explains that The Third Step is a ‘reference to the stage in AA when addicts make a decision “to turn our will and our lives over to the care of God”’. Dark clouds ‘theatrically open to illuminate the crucifix on a nearby church tower’. ‘The burial ground becomes holy ground’ and the poor, bare, forked animal ‘drags himself into the zone of brightness like a contemporary Lazarus come forth from a pitted, concrete sepulchre’ (Kohan 2012: 76).

Howson, this crawling figure, and Nebuchadnezzar all come to a moment of restorative realization about themselves and about God. In this painting Howson captures visually the internal moment when realization appears and, to quote William Blake, ‘the doors of perception’ become ‘cleansed’ (Blake 1979: 188).

References

Blake, William. 1979. The Marriage of Heaven and Hell in The Complete Poems (Harmondsworth: Penguin Books)

Heller, Robert. 2003. Peter Howson (London: Momentum Books)

Fraser, Steven. 2002. 'Howson sees the Light in the Kirk 3 March 2002', The Scotsman.

Kohan, John A. 2012. ‘Peter Howson and the Harrowing of Hell’, Image Journal, 76.

William Blake :

Nebuchadnezzar, 1795–c.1805 , Colour print, ink, and watercolour on paper

Arthur Boyd :

Nebuchadnezzar's Dream of the Tree, 1969 , Oil on canvas

Peter Howson :

The Third Step, 2001 , Oil on canvas

Renewal from Adversity

Comparative commentary by Jonathan Evens

The tales about King Nebuchadnezzar II told in the book of Daniel appear to be stories of overweening pride, with Nebuchadnezzar, like Icarus, reaching too high and being thrown back to the ground. The proverbs and phrases that seem most naturally to capture the moral of this story—‘how are the mighty fallen’, ‘pride comes before a fall’, and having ‘feet of clay’—link it to other biblical texts with comparable concerns (2 Samuel 1:27; Proverbs 16:18; Daniel 2:31–32).

Nebuchadnezzar would not have been the first ruler to have sought to immortalize his image through a statue (Daniel 3:1–7), and we can all readily recall examples of statues of the once powerful, such as those of Lenin, Saddam Hussein, and Confederate heroes, that have subsequently been toppled.

As Robert Graves writes in his poem 'Nebuchadnezzar’s Fall':

Here for the pride of his soaring eagle heart,

Here for his great hand searching the skies for food,

Here for his courtship of Heaven's high stars he shall smart,

Nebuchadnezzar shall fall, crawl, be subdued. (Knopf 1920: 37)

The works of art in this exhibition do not focus primarily on Nebuchadnezzar’s fall, however. While William Blake’s image does foreground Nebuchadnezzar’s bestial nature, with even the king’s own eyes directed downwards at the ground on which he crawls, Blake wants to alert us to a different possibility. Nebuchadnezzar’s concentration on the material as reality—seeing with the eye instead of seeing through the eye—means that his sight has narrowed so that he cannot see infinity. We are to look further.

By contrast the figure in Peter Howson’s The Third Step looks up from the graveyard in which he crawls—and away from himself—to focus his gaze on Christ. Step three in the Twelve Step programme of Alcoholics Anonymous—'a decision to turn our will and our lives over to the care of God as we understood him’—is meant to help alcoholics rely on something other than themselves to help them abstain from drinking. Similarly, in Arthur Boyd’s painting, we see Nebuchadnezzar looking up. His upward gaze is in the same direction as the growth of the tree—a reversal of his fall and the beginning of his restoration.

In their paintings, Howson and Boyd show more interest in rehabilitation and restoration than in fall. Meanwhile, Blake, in his work, focuses more on the sensual slavery represented by Nebuchadnezzar’s fallen state—a sensuality which inhibits awareness of what is spiritual—than on the pride which led to that state. Taken together, though each in its own way, these three works can be seen as inviting us to grow into the divine life, overcoming the bestial self that we see criticized in Blake’s Nebuchadnezzar. It is as we look away from ourselves and abandon our own self-reliance—the moment of realization, the ‘cleansing’ of the ‘doors of perception’ (Blake 1979: 188)—that we are able to see God. Through such moments, we may ourselves become icons revealing the divine.

So, despite initial appearances Daniel 4 does much more than present us with the moral lesson that ‘pride comes before a fall’. The chapter’s concerns with exile and renewal give us in microcosm one of the central arguments of the book of Daniel as a whole.

The prophet Jeremiah sent a letter to all the people Nebuchadnezzar had carried into exile from Jerusalem to Babylon (Jeremiah 29). This letter encouraged the exiles to settle down and seek the peace and prosperity of the city to which they had been carried against their wills. Though written a long time later than Jeremiah’s letter, much of the book of Daniel complements it by showing God at work through the exiles in Babylon—to such an extent, indeed, that Nebuchadnezzar himself eventually acknowledges the sovereignty of God. Through his time away from the affairs of court, Nebuchadnezzar had his own exile experience; one which, for all its mental distress, ultimately restored him to a greater sense of wholeness and well-being.

Samuel Wells suggests that Judah had previously loved God primarily for ‘the promise of land, king and temple’. When deprived of these things, Judah in exile ‘discovers that it is closer to God than ever it was in the Promised Land’ (Wells 2017: 3). Such renewal, concludes Wells, ‘invariably comes out of adversity’ (Wells 2018: 7).

This is perhaps an insight for a contemporary Church smarting from its loss of influence in a post-Christendom and post-modern society where it is one among many faiths and one among many voices in the public square. One response to these circumstances is to denounce and oppose the perceived godlessness of earthly powers. Some other parts of the book of Daniel seem to commend just this. But Jeremiah’s letter and the example of Daniel under Nebuchadnezzar’s rule suggest that renewal will come if the Church settles into its changed circumstances and seeks the peace and prosperity of society.

References

Blake, William. 1979. The Marriage of Heaven and Hell in The Complete Poems (Harmondsworth: Penguin Books)

Graves, Robert. 1920. Country Sentiment (New York: Alfred A. Knopf)

Wells, Samuel. 2017. ‘Catalysing Kingdom Communities’, General Assembly of the Church of Scotland, May 23, 2017, www.churchofscotland.org.uk [accessed 7 July 2019]

———. 2018. ‘A Future that’s Bigger than the Past: Renewal and Reform in the Church of England’ (Background paper presented at Renewal & Reform, Church of England), www.churchofengland.org/about/renewal-reform/theological-reflections [a… 7 July 2019]

Commentaries by Jonathan Evens