1 John 3

Children of God

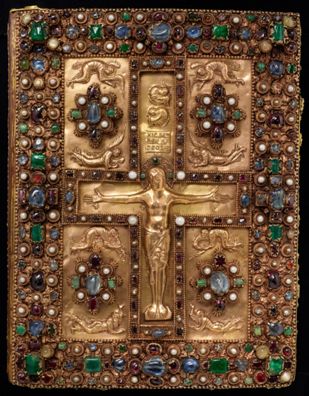

Unknown German artist

Lindau Gospels, Front cover (St Gall, Switzerland), 880–99, 350 x 275 mm, The Morgan Library & Museum, New York; Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan (1837–1913) in 1901, MS M. 1, Photo: The Morgan Library & Museum, New York

Out of Death into Life

Commentary by Taylor Worley

1 John 3 builds its exhortations on the perfect obedience of Christ: ‘he is pure’ (v.3), ‘in him there is no sin’ (v.4), and ‘he is righteous’ (v.7). His obedience, 1 John 3 relates, culminated in the cross where ‘he laid down his life for us’ (v.16).

While artisans, both ancient and modern, have often struggled to depict the other-worldly glory of the triumphant Christ, we can see such tension supremely represented here in the Pierpont Morgan Library’s chief prize. The gilded and bejewelled cover of the Lindau Gospels conveys both the brutality of the cross and the resurrection power that overcame it.

On a cover that employs 327 precious gems, the central figure of Christ on the cross emerges along with ten mourning witnesses. These include the figures of the sun and moon (Joel 2:10), inscribed within the cross above the figure of Christ, along with two pairs of angels each flanking the top of the cross. Mirroring the poses of the angels above are four human figures below. In their postures, Christ’s mother, St John, and the two female mourners below them, suggest their agony as witnesses. Upon close examination, we observe etched drops of blood from the nails in Christ’s hands and feet.

The repoussé technique of the goldsmiths (whereby a relief is created by hammering the shape from the inside) makes for a smooth, naturalistic presentation. Such a technique can be read as an analogy of the resurrection power that brought the crucified Messiah back from the grave—working life from the inside out to a glorious appearance. Indeed, the sufferer appears as a celebrated victor (a Christus Triumphans), wounded but now restored and standing with great poise and self-assurance. The jewelled decorations placed centrally in the four gold rectangles surrounding the cross are raised slightly on lion’s feet, like tiny pedestals. They protect the central figure and ensure his impeccable appearance.

‘When he appears … we shall see him as he is’ (v.2). With these words, the Epistle looks to the parousia (the second coming) as a moment of apocalypse, or ‘unveiling’. There is, likewise, something apocalyptic about the Lindau Gospels’ cover. Indeed, in its ornate gems and gold-work, some admirers see an evocation of the beauty of the heavenly New Jerusalem in the final chapters of Saint John’s Revelation (21:9–21).

References

Lindau Gospels: The Morgan Library & Museum website https://www.themorgan.org/collection/lindau-gospels [accessed 6 October 2021]

Rogier van der Weyden

The Last Judgement (The Beaune Altarpiece), c.1445–50, Oil on oak, c. 220 x 548 cm (open), Hôtel-Dieu, Beaune; Erich Lessing / Art Resource, NY

Christ’s Glorifying Love

Commentary by Taylor Worley

The First Epistle of John distinguishes sharply between those destined for life and glory and those who are ‘of the devil’ (3:8). It would be difficult to find a more dramatic example of such a contrast than Rogier van der Weyden’s magnificent polyptych altarpiece.

Nicolas Rolin, the wealthy Chancellor of Burgundy, and his wife Guigone de Salins founded the Hôtel-Dieu in Beaune, France, in 1443. Recent outbreaks of the plague along with the impoverishing effects of the Hundred Years’ War meant that Beaune was in dire need of a hospital. This palace of the poor, as its historic nickname attests, offered the dying both physical and spiritual comfort. At Rolin’s insistence, the great hall’s design allowed patients direct sight of the hospital’s chapel and Van der Weyden’s impressive altarpiece.

Unlike earlier panelled altarpieces of this period, Van der Weyden presented a single, panoramic scene rather than a multiplicity of smaller ones: a grand and imposing vision of Christ’s final judgement.

This victorious Christ evokes his supreme authority while openly displaying his wounds. The angels in white that surround him bear the cross along with the objects of his torture, but he is seated in majesty on a rainbow above the Archangel Michael. He rests his feet on a globe (Hebrews 10:13), and presides over the reckoning with a lily for the just on his right (a symbol of mercy) and a sword for the damned on his left (a symbol of justice). Another group of angels dressed in red attend the Archangel in summoning the dead for judgement. ‘By this it may be seen who are the children of God, and who are the children of the devil’ (v.10).

Perhaps most remarkable about this work is the voluminous, fiery-gold cloud that surrounds Christ and envelops a gathering of saintly witnesses. The scale and prominent placement of these men and women contribute to the compositional balance of the scene but more importantly emphasize their place with Christ in glory. These, in 1 John’s words, ‘are God’s children’ (v.1) and who are now ‘righteous, as he is righteous’ (v.7). Together, they constitute the heavenly order that overwhelms the earthly order. As the golden cloud of Christ’s glory fills nearly the entire span of the seven horizontal panels, and elevates these saints, the altarpiece testifies to 1 John’s expectation: ‘[W]hen he appears we shall be like him, for we shall see him as he is’ (v.2).

Paul Chan

The 5th Light, from The 7 Lights, 2007, Digital video projection, 14 mins, Installed at the New Museum in 2008; © Paul Chan, Courtesy of the artist and Greene Naftali, New York

Love or Lawlessness

Commentary by Taylor Worley

1 John 3 characterizes sin as lawlessness. We can find a profound metaphor for such troubling and chaotic disorder in Paul Chan’s (b.1973) series of video projections called The 7 Lights.

Known for his complex, large-scale video work, Paul Chan regularly blurs the line between art and activism. In the course of his ongoing experiments with video art, he took up the challenge of presenting shadows (hence his title, implying the pictorial representation of light’s negation).

Inspired by observing the play of light on the floor of his apartment, Chan created a set of digital animations depicting an inversion of the seven days of creation, a kind of ‘un-creation’ narrative. These videos are projected on the gallery floor. As the artificial daylight of these videos rises and changes over time, ominous shadows appear and move across the picture plane.

The work opens with familiar shadows of telephone poles, streetlights, trees, or birds—all animations digitally drawn by the artist. As the videos progress, objects begin to float upward slowly and tear apart in mid-air. Many are quite small (eyeglasses, cell phones, or an iPod) and others are much larger (pets, city-dwelling animals, a bicycle, a police car, or a city train).

Suddenly shadows of human bodies drop through the picture plane. Only a few bodies fall at first; mostly one at a time, but sometimes in pairs or groups. They descend—presumably to their deaths—with a speed and force that recalls the haunting news footage of those leaping from the burning towers of the World Trade Center on 11 September 2001. The initially quaint, absurd scenes are thus rendered chaotic disasters. Chan’s windowpanes continue to fill until objects overcrowd the view and all is shadow. Beginning with the warm hues of dawn and closing with cooler night-time blues and greys, each day unfolds in 14-minute sequences that loop endlessly.

The 5th Light (shown here) stands out for its startling inclusion of assault rifles. Humans have a share in the world’s de-creation in the wars we start, the oppression we inflict, and the inequalities we allow.

Likewise, when 1 John states that ‘no murderer has eternal life abiding in him’ (v.15), it recalls Cain, whose murder of his brother was the first homicide. Chan’s apocalyptic fantasy not only dazzles and disturbs, but in its unveiling of the powers and principalities of this world, it also judges our lawlessness.

References

Chan, Paul, and Martha Rosler. 2006. Paul Chan, Martha Rosler: Between Artists. (New York: A.R.T. Press)

Chan, Paul, et al. 2007. Paul Chan: The 7 Lights. (London: Serpentine Gallery)

Unknown German artist :

Lindau Gospels, Front cover (St Gall, Switzerland), 880–99 , 350 x 275 mm

Rogier van der Weyden :

The Last Judgement (The Beaune Altarpiece), c.1445–50 , Oil on oak

Paul Chan :

The 5th Light, from The 7 Lights, 2007 , Digital video projection

Love One Another

Comparative commentary by Taylor Worley

Despite its captivating array of literary imagery, 1 John 3:1–16 offers a clear and emphatic imperative to ‘love one another’ (v.11). The passage underscores the grave importance of its plea by sharing a series of stark binaries; such as ‘children of God’ (v.1) versus ‘children of the devil’ (v.10), ‘abides in him’ (v.6) versus ‘abides in death’ (v.14), the righteous brethren (v.7) versus the world (v.13), etc.

Amid the pull of these dualities, the reader is called decisively to embrace one and resist the other. The vision of Christ’s glory, so 1 John relates, makes possible a transformation akin to his for anyone who ‘abides in him’ (v.6), who has ‘seen him or known him’ (v.6), and who is ‘born of God’ (v.9). 1 John 3 also warns sternly against disregarding his example and continuing in sin.

Joyfully, 1 John presents the Son of God as the exemplar of what it is to overcome the world and to triumph in glory. ‘He is pure’ (v.3). Representing the crucifixion in a highly stylized manner typical of the Middle Ages, the cover of the Lindau Gospels conveys this purity. There is poignancy in his Passion, but the smoothness and refinement of the metalwork render his monumental form exquisite—projecting into the viewer’s space through the use of repoussé relief. This Christ Triumphant is a glorious sufferer, evoking the kind of reverence and awe that the author of 1 John seeks to elicit, too, as he issues his ethical summons that ‘every one who thus hopes in [Christ] purifies himself’ (v.3).

Visual traditions of the Last Judgement speak directly to the efforts of those seeking to purify themselves. Most notably, Rogier van der Weyden’s Beaune Altarpiece can be read as providing a picture of the redeemed community that 1 John 3 seems to envision. Here the Deësis form (a traditional iconography wherein the central Christ is flanked by his Mother and St John the Baptist in supplication) also gathers balanced rows of the twelve apostles with additional rows of as yet unidentified male and female figures. This visual architecture allows the composition to make a decidedly theological statement. Fifteenth-century naturalism takes on a mystical significance as these regal saints are rendered alongside Christ in his glory. Such rendering speaks to 1 John’s staggering claim that ‘God’s nature abides in [them]’ (3:9) Indeed, the believer’s journey in sanctification finds a particularly apt image here as these witnesses gaze upon the glorious judge and thereby symbolize the transformative logic of 1 John 3: ‘[W]hen he appears we shall be like him, for we shall see him as he is’ (v.2).

At the same time, Van der Weyden’s altarpiece also depicts the guilty and thus acknowledges that some will reject this call to love. They will remain ‘guilty of lawlessness’ (v.4) and abide in death. As 1 John 3 relates, the inherent tension in choosing the righteous way remains, because ‘it does not yet appear what we shall be’ (v.2). The charge to love one another comes finally in the form of two extreme examples: a negative case, ‘Any one who hates his brother is a murderer, and you know that no murderer has eternal life abiding in him’ (v.15) and a positive case, ‘By this we know love, that he laid down his life for us; and we ought to lay down our lives for the brethren’ (v.16).

This life and death contrast is resonant with Paul Chan’s arresting inversion of creation in The 7 Lights. Mimicking what can be seen in the light cast across a floor from an apartment window, his video projections toy with ideas of the end of the world. In the hallucinatory effects of its imagery, the 5th Light in particular sets forward a profound moral drama. It announces that the present conditions of the world must change. While Chan’s work is ambiguous about whether this change will bring redemption or destruction, it seems that no one escapes the imagined reckoning. Coincidentally, like the fifth of seven signs in John’s Gospel where Jesus demonstrates his power over the deadly sea by walking on the stormy waters (John 6:16–21), the 5th Light recalls a different sort of storm: the epidemic of gun violence that terrorizes so many lives today. This fear is met in Chan’s video with a picture of the imminent dismantling of these weapons of war and death. Such destruction of arms evokes the rationale behind 1 John’s exhortation: ‘The reason the Son of God appeared was to destroy the works of the devil’ (3:8).

In its haunting fashion, then, the disarming of temporary powers in Chan’s 5th Light allows us to see ourselves, one another, and this present world, differently. In the process, perhaps, we can feel the call to self-giving love with renewed urgency.

Commentaries by Taylor Worley