Jude 1

Jude the Adjurer

Unknown Ethiopian artist

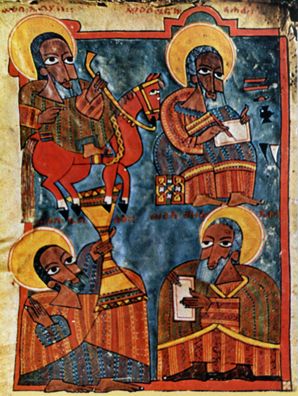

Elijah, Enoch, Ezra, and Elisha, 15th or 16th century, Ink on parchment, Gunda Gundē Monastery, Tegrāy Ethiopia; C3-IV-2 f. 1v, akg-images / Fototeca Gilardi

The Eligibility of Enoch

Commentary by Kelsie Rodenbiker

This is a page from a manuscript written in Ge’ez, ancient Ethiopic, from the Gunda Gundē monastery in the Tegrāy region of Ethiopia. It shows four biblical figures from the Hebrew Bible (clockwise from top left): Elijah, Enoch, Ezra, and Elisha.

Enoch holds a writing instrument and a page or tablet, with extra pens and ink to his side. That he is shown in the company of other prophets from the Hebrew Bible, as well as actively writing, is significant. While Enoch appears in Genesis, he does not prominently feature—the most notable thing about him is that he lived 365 years before ‘he was no more, because God took him away’ (5:22–24).

Elijah, too, was ‘taken up’ by fiery horses and chariots, after which Elisha inherited his cloak and prophetic mantle (2 Kings 2:10–15). Ezra wears several hats in both canonical and now-noncanonical literature. He is remembered as a priest and scribe, responsible for leading the renewal of Israel’s reading and adherence to the law in the wake of the destruction of the Temple (Nehemiah 8). He is also celebrated as a prophetic figure like Moses who dictates new revelatory scriptures (4 Ezra 14:38–48).

Like Elijah, Enoch did not die; like Elisha he wore a prophetic mantle; like Ezra, he wrote scripture. And as with Ezra, scripture attributed to Enoch now falls outside the widely accepted biblical canon. The author of Jude introduces Enoch as an authoritative prophetic figure, ‘seventh from Adam’, and then quotes from the text of 1 Enoch (Jude 14–15). In other words, as we see in the Ethiopian manuscript illustration, the author of this New Testament apostolic epistle values Enoch both as a prophet and as an author of scripture.

Nicolai Abraham Abildgaard

The Archangel Michael and Satan Disputing about the Body of Moses, c.1782, Oil on canvas, 49.7 x 61.7 cm, ARoS Art Museum, Aarhus;

The Matter of Moses

Commentary by Kelsie Rodenbiker

At the end of Deuteronomy, at the age of 120, the prophet Moses climbs Mount Nebo and looks over the land the LORD had promised to his ancestors (34:1–4). He dies there, destined not to enter the land himself after disobeying the LORD’s instructions and striking, rather than only speaking to, a rock to draw out water (Numbers 20:10–12; Deuteronomy 3:23–28). Moses is buried in Moab, but a mystery remains: ‘to this day no one knows where his grave is’ (Deuteronomy 34:6).

This lacuna is filled in by a later text, the Assumption of Moses, which is an apocryphal text mentioned by ancient Christian theologians such as Origen and Clement of Alexandria. The story goes that after Moses’s death, Michael the Archangel was commissioned with the task of burying him. The Devil confronted the Archangel, and they argued over what would become of Moses’s body. The Devil wanted to claim the body based on two arguments: first, that to him belonged presidency over material things, and bodies are matter; second, that Moses had murdered an Egyptian (see Exodus 2:11–15). In response, Michael rebuked the Devil, asserting that God made humanity and is therefore Lord even over matter.

It is this account that is referred to in Jude 8–9, making use of Michael’s rightful restraint in refusing to blaspheme ‘even the devil’, mindful of the singular judgment of God.

Nicolai Abildgaard’s eighteenth-century painting depicts just this moment. Challenging the serenity and order of then-popular neoclassical style, Abildgaard’s painting is dynamic in its depictions of movement, weather, and the threat of violence.

Atop the mountain, with billowing clouds as a backdrop, a naked Devil with wild red hair stands over the body of Moses, who still clutches the tablets of the Ten Commandments—a symbolic reminder of his role as prophet and mediator. With a sword raised, Michael gestures to Moses, claiming the body. The author makes this the centre point of his letter, emphasizing Michael’s role as an angelic intermediary who knows his place within the order of creation.

Gustave Doré

The Death of Korah, Dathan, and Abiram, from Doré Bible, 1866, Engraving, Sammlung Archiv für Kunst und Geschichte, Berlin; akg-images

The Calamity of Korah

Commentary by Kelsie Rodenbiker

Gustave Doré designed a series of wood engravings of biblical subjects in the nineteenth century, of which this work, showing a fiery chasm engulfing Korah and his followers, is one.

In Numbers 16, Korah, along with Dathan, Abiram, and 250 other men, challenges the divinely-appointed authority of Aaron as the high priest—and thus the authority of the LORD (vv.1–40). In retribution for their rebellion, ‘the earth opened its mouth and swallowed them, their households, and all the people who belonged to Korah with all their possessions’ and then it closed back up over them and fire consumed the other 250 men (vv.31–34).

The engraving suggests just how severe the impact of Korah’s rebellion was on the assembly. The Ark of the Covenant tumbles forward, barely saved by a rock from sharing in Korah’s doom; and we see a tent, collapsed and ripped, which is also precariously close to teetering over the chasm’s edge. This might be Korah’s tent, or possibly even the Tent of Meeting (given its proximity to the Ark of the Covenant). If so, then two central symbols of priesthood and relationship to God are in jeopardy.

The total destruction of Korah and everything and everyone who belongs to him presents a hyperbolic account of what happens to those who dare to challenge God and God’s appointed representatives. This is also the context in which the author of Jude makes use of this example of supposedly deserved destruction.

In Jude 11, we find a cluster of figures from the scriptural past presented as a warning to those who would do as they have done, following ‘the way of Cain’, ‘the error of Balaam’, and ‘the destruction of Korah’. As the climactic figure in this quick succession of negative archetypes, Korah’s example is the most extreme. Like Cain, who murdered his brother (Genesis 4:1–15) and who later becomes a paradigmatic false teacher, and Balaam, who accepted a bribe to prophesy against Israel (Numbers 22–24), Korah and his kin illustrate for Jude the high price of rebellion against God’s authority.

Unknown Ethiopian artist :

Elijah, Enoch, Ezra, and Elisha, 15th or 16th century , Ink on parchment

Nicolai Abraham Abildgaard :

The Archangel Michael and Satan Disputing about the Body of Moses, c.1782 , Oil on canvas

Gustave Doré :

The Death of Korah, Dathan, and Abiram, from Doré Bible, 1866 , Engraving

Teaching by Example

Comparative commentary by Kelsie Rodenbiker

Jude is a letter claiming to be from Jude, ‘slave of Jesus Christ and brother of James’ (Jude 1), which is a subtle way of suggesting that the attributed author was also a brother of Jesus. The author writes to warn readers of false teachers (‘certain people’) who have snuck into their communities to lead them astray into ungodliness (Jude 4, 12–13, 16).

The above artworks and their corresponding pericopes in Jude all share in common the illustrative participation of exemplary figures from the Jewish scriptural past: Michael the Archangel, Korah, and Enoch. In fact, the whole structure of Jude is driven by these scriptural figures.

There are two clusters of three negative examples, capped off by a positive one, all of which function to characterize the false teachers against whom Jude is writing. The unbelieving generation of Israelites who perished in the wilderness (Jude 5), the inhabitants of Sodom and Gomorrah who went after ‘strange flesh’ (that is, after angelic beings; Jude 6), and the sinful angels who transgressed their place in heaven all co-illustrate the destruction awaiting those who trespass their proper place in the order of creation (Jude 7). This negative trio is followed by the example of Michael the Archangel, who knows his position so well that he declines to blaspheme even the Devil (Jude 8–9).

The second cluster is found in Jude 11, which pronounces woe upon those who ‘have gone the way of Cain, and for pay … have given themselves up to the error of Balaam, and perished in the rebellion of Korah’. For the author of Jude, this trio illustrates the punishment awaiting those who lead others astray. To follow in the way of Cain could indicate either or both murder or apostasy, since Cain became known as a false teacher. The error of Balaam was not only greed in accepting a bribe, but also false teaching, as he instructed Balak in how to swindle and defeat the Israelites (see Numbers 25:1–9; 31:16; Revelation 2:14). Korah’s rebellion was also a matter of bad instruction: Korah, Dathan, and Abiram led a rebellion against the priestly authority of Aaron. They are followed shortly by the figure of Enoch, who provides both a contrasting example of true instruction and a prophetic pronouncement about the coming destruction of the ungodly, including Jude’s opponents, the deceitful false teachers (Jude 14–15).

Throughout Jude, there are many links to texts of the Hebrew Bible, particularly within the context of illustrative scriptural characters. In addition to these intertextual relationships, there are also significant connections to what is now widely considered to be noncanonical literature. Such connections challenge a closed and definitive notion of the biblical canon.

Michael and the Devil’s argument does not appear anywhere in the Hebrew Bible—Michael himself hardly features. The dispute is known instead from the ‘Old Testament Pseudepigrapha’: a body of works attributed to or narrating the lives of Old Testament figures such as Adam and Eve, Moses, Abraham, Ezra, Joseph, and Asenath—and also Enoch. Most Christian traditions today do not accept Enochic literature as canonical. But for the Orthodox Tewahedo tradition (to which the manuscript illumination in this exhibition belongs) as well as for many early Jews and Christians, Enoch was indeed a prophetic figure. In citing 1 Enoch, Jude honours a text that—like the illumination here—insists on Enoch’s authoritative authorship (see 1 Enoch 81:1–2; 82:1; 92:1).

Like the text of Jude, traditions of visual art are frequently porous, marked by associative connections, dynamic combinations, and inventive transmissions. Art has the power both to reflect an artist’s perspective and intention and to influence later perspectives on the scriptural episodes that are depicted, particularly when it is the artwork, not the text, that sticks best in the memory of viewers.

Many people encountered—and still encounter—the Bible not primarily through reading and text but through visual depictions, in various media—painting, sculpture, film, etc. The striking energy of Gustave Doré’s and Nicolai Abildgaard’s works provide the sort of drama that can definitively transform a text’s reception.

What this means for the historical development of the biblical canon and the many attempts to stabilize scripture is that tradition is impossible to fully tame—the Bible is not a concrete singularity, but rather an omnibus of many different languages, cultures, manuscripts, traditions, perspectives, depictions. Biblical tradition is as canonically diverse as the communities that produced, preserved, and still use it: Hebrew Bible and New Testament, Orthodox, Catholic, Protestant. It is in just this untameable vein that it remains so visually and vividly alive through art.

Commentaries by Kelsie Rodenbiker