Nehemiah 7:73–8:18

‘To Meet with Joy in Sweet Jerusalem’

Gustave Doré

Ezra Shows the Ten Commandments on Tablets, from Doré Bible, 1866, Engraving; Universal History Archive / UIG / Bridgeman Images

‘The Bloody Book of Law’

Commentary by Allen Dwight Callahan

This engraving is by Gustave Doré (1832–83), a French artist famous for his printed illustrations of over 100 books, among them Dante’s Divine Comedy, Cervantes’s Don Quixote, and, most famously, the Bible.

Doré’s illustrated Bible in folio format, published in 1865, was a runaway international bestseller. It is featured in a scene in the Stephen Spielberg film Amistad, in which two imprisoned African slaves, though illiterate, ‘read’ the story of Jesus through Doré’s illustrations of scenes in the Gospels.

Its subject is Nehemiah 8:2–4: ‘accordingly, the priest Ezra brought the law before the assembly ... Ezra stood on a wooden platform that had been made for the purpose’. The ‘book of the law’ that Ezra brings forth should be a scroll. But here Doré gives an iconographic nod to Israel’s first encounter with divine Law at Sinai. Ezra points to what is inscribed on a large tablet with twin lobes at the top, suggesting the two ‘tables of the law’ that Moses delivered to the Israelites after his forty-day audience with God. Doré’s representation concurs with widely held rabbinic esteem for Ezra as a second Moses who delivers the Law of God again to the wayward Israelites: Ezra saved the Law from oblivion (Babylonian Talmud Sukkah 20a); he was the equal of Moses, and would have been the one to deliver the Law to Israel had not Moses done so first (Babylonian Talmud Sanhedrin 21b).

This second dispensation of holy Law, however, is attended with none of the sound and fury of the first at Sinai. Ezra stands not at the foot of a volcanic mountain, but atop a handmade pedestal facing the town square. And unlike the cowed multitude at Sinai, Ezra’s hearers do not maintain a horrified distance but instead draw near, some close enough to touch him. At lower left, a woman bows her head as a man standing nearby appears to look disdainfully upon her—an ominous intimation of things to come.

References

Richardson, Joanna. 1980. Gustave Doré (London: Cassell)

Julius Schnorr von Carolsfeld

Ezra Reads the Law, from Die Bibel in Bildern (Leipzig, G. Wigand), 1860, Woodcut; p.308, Digital image courtesy of the Getty's Open Content Program

‘Words, Words, Words’

Commentary by Allen Dwight Callahan

Julius Schnorr von Carolsfeld’s Ezra Reads the Law is a woodcut that appears in Carolsfeld’s folio edition of the Bible, Die Bibel in Bildern (The Bible in Pictures). It was published in Leipzig in thirty parts from 1852 to 1860. An English edition followed the original German in 1861.

Schnorr von Carolsfeld was associated with a group of painters who called themselves the Nazarenes, or St Luke’s Brotherhood (Lukasbund), that eschewed modern styles along with typology and allegory. Schnorr von Carolsfeld himself especially took a literal, narrative approach to his subjects, finding his inspiration in early Renaissance art and, more specifically, in the works of Albrecht Dürer.

Here Ezra, in ecclesiastical robes and bishop’s mitre, is every inch the medieval Catholic priest. He speaks from an elevated lectern, Schnorr von Carolsfeld’s visual interpretation of Nehemiah 8:4–5:

The scribe Ezra stood on a wooden platform that had been made for the purpose ... And Ezra opened the book in the sight of all the people, for he was standing above all the people.

The scribe raises his right hand, gesturing in the direction of his rapt audience. Some receive his words with adoration, others, in apparent agony (‘For all the people wept when they heard the words of the law’; Nehemiah 8:9). Ezra is flanked by walls of neatly cut stonemasonry; an open archway at centre right, presumably ‘the Water Gate’ (Nehemiah 8:5), is occupied by some of Ezra’s more distant hearers. At far right, a portion of the wall blocks the sunlight, casting mid-morning shadows on an adjoining wall of the courtyard (‘[Ezra] read from [the law] facing the square before the Water Gate from early morning until midday’; Nehemiah 8:3).

Beyond the wall at upper right, outsiders, some of them no more than diminutive silhouettes on the horizon, go about their business and keep their distance. Earlier in the narrative Nehemiah had rebuffed efforts of the indigenous people to become involved in his project, telling their leaders, ‘you have no share or claim or historic right in Jerusalem’ (Nehemiah 2:20).

The separation enforced by Nehemiah’s walls is met here with the separatism enjoined by Ezra’s words.

References

Schiff, Gert et al. 1981. German Masters of the Nineteenth Century: Paintings and Drawings from the Federal Republic of Germany (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art), pp. 272–73

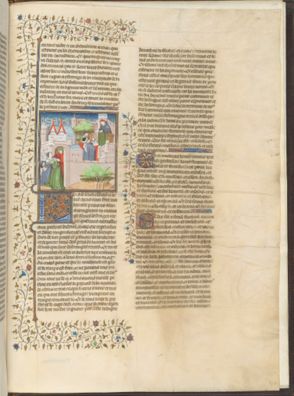

Workshop of the Boucicaut Master

Ezra: Oath of Children of Israel, from Bible Historiale, c.1415, Illuminated manuscript, 450 x 330 mm, The Morgan Library & Museum, New York; Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan, 1910., MS M.394 fol. 258r, Courtesy of The Morgan Library & Museum, New York

‘The Strongest Oaths’

Commentary by Allen Dwight Callahan

This miniature illumination in the French Gothic style, dated c.1415, is entitled Ezra: Oath of Children of Israel. It is part of a Bible Historiale, a popular medieval text combining biblical narrative, legend, and religious commentary.

The scene at upper right takes place within the walls of the city: an audience of five men look up to Ezra, who gestures toward them as he holds forth, standing in a draped pulpit. At lower left just above a square ivy-rinceaux foliate decoration, two women are pushed out of the city gate of Jerusalem by man in a turban.

The scene suggests what occurs only later, not in the book of Nehemiah but at the end of the book of Ezra: the annulment of all marriages between Jerusalemite men and indigenous women and the expulsion of those women and the children who are the issue of those unions (see Ezra 10). The illumination reflects the version of the narrative in the deuterocanonical 1 Esdras (canonical in the Greek and the Russian Orthodox Churches, not so recognized by the Roman Catholic Church, though it appears in an appendix to the Latin Vulgate Bible.) There, the expulsion of non-Israelite spouses immediately follows Ezra’s declamation:

Then the men of the tribe of Judah and Benjamin assembled at Jerusalem ... Ezra stood up and said to them, ‘You have broken the law and married foreign women, and so have increased the sin of Israel. Now then make confession and give glory to the Lord the God of our ancestors, and do his will; separate yourselves from the peoples of the land and from your foreign wives’. Then all the multitude shouted and said with a loud voice, ‘We will do as you have said’. (1 Esdras 9:5–10)

1 Esdras leaps at once to where Nehemiah’s narrative is moving more gradually: it is after a period of reading the Law and fasting that the Jerusalemites ‘separated themselves from all foreigners’ (Nehemiah 9:1–3); and ‘[w]hen the people heard the law, they separated from Israel all those of foreign descent’ (13:3).

The man in the turban here, then, may well be expelling from the city his very own wives.

Gustave Doré :

Ezra Shows the Ten Commandments on Tablets, from Doré Bible, 1866 , Engraving

Julius Schnorr von Carolsfeld :

Ezra Reads the Law, from Die Bibel in Bildern (Leipzig, G. Wigand), 1860 , Woodcut

Workshop of the Boucicaut Master :

Ezra: Oath of Children of Israel, from Bible Historiale, c.1415 , Illuminated manuscript

‘The Wide Arch of the Ranged Empire’

Comparative commentary by Allen Dwight Callahan

This episode is a vignette of imperialism, of colonialism, of racism, all riding on the coat-tails of Holy Writ: of those who aided and were aided by empire, laid claim to the land of others, and then excluded those others from that claim. And after the land grab, revelry. All mandated by the Word of God.

It is a vignette of Ezra, one of the Bible’s few pulpit-pounders, pounding one of the Bible’s few pulpits. The Hebrew canon does not separate the books of Ezra from Nehemiah until the fifteenth century; in the Septuagint, they are one work. But it is here, in the book that bears Nehemiah’s name, that Ezra takes centre stage.

The Southern Kingdom of Judah fell to the Babylonians in the sixth century before the Common Era, suffering a deportation of its elite to Babylon. Some descendants of that elite returned to Judea after the fall of the Babylonian Empire under the patronage of its Persian successor: the Persian emperor Cyrus is credited with restoring gods and peoples dislocated by earlier regimes to their respective ancestral lands (2 Chronicles 36:22–23; Ezra 1:1–4; see Isaiah 45:1–25).

Ezra’s narrative affords the connection between the ‘returnees’ and the old Temple that the Babylonians had destroyed. Throughout the Babylonian exile, Israelites continued to live on the western side of the Jordan. They had survived the destruction of the Northern Kingdom by the Assyrians a century before the Babylonians destroyed Jerusalem: 2 Chronicles 30:6, 10–11 calls them ‘the remnant of those that escaped’. It is the descendants of this remnant that Nehemiah confronts—and rejects—in his efforts to rebuild Jerusalem.

The ‘return’ was a creation of a new people with a new cult, centred on a new temple under Persian patronage. With Nehemiah, though of Judaean ancestry, as its Persian administrator, the new Jerusalem sucked from the teat of the imperial capital of Susa, which provided financial and material resources as well as a transplanted elite. Born and raised in the metropole, they were in Jerusalem but not of it.

The newly-minted Jerusalemites unanimously request that Ezra read the Law to them (Nehemiah 8:1). Ezra reassures them that the joy of the Lord will protect them against the judgement due their transgressions (8:10). The people resolve to study the Law (8:13) just as Ezra had done (see Ezra 7:10). Informed by their study, they celebrate the Feast of Tabernacles for the first time since the days of Joshua (Nehemiah 8:17).

The book of Nehemiah thus gives us a biblical precedent for divinely-ordained imperialist claim-jumping. In the now-canonical proclamations of the high priest Ezra, what was authorized by Holy Writ has now become authorized in Holy Writ. Henceforth, the Bible would provide this prooftext for racial segregation and nationalist exceptionalism; for separating families at the border—wives torn from their husbands, fathers torn from their children; for erecting a wall to ‘defend’ a border in no way under attack, making of neighbours aliens and enemies; for the People of God as gated community—affirmed in the words of Ezra and in the affirmations of his parvenu Jerusalemite congregation.

Apparently, none of our artists is troubled by any of this. Their concerns lie elsewhere. In Gustave Doré’s visual literalism, the bearded Ezra sports tasselled robes and a turban—the ‘exotic’ garb of a stereotyped ancient Near Eastern figure. He is a carefully etched study in French Orientalism. In the woodcut of Julius Schnorr von Carolsfeld and in the illumination of the Boucicaut Master, Ezra presides like a bishop over his ‘diocese’ of Jerusalem, declaiming to his penitent congregation a ‘canon law’ that he translates for them from the sacred, alien tongue in which it is written.

The book of Nehemiah is written entirely in Hebrew; the book of Ezra contains documents in Aramaic (Ezra 4:7–6:22; 7:12–26), the imperial lingua franca. This was the tongue into which Ezra had to translate the Hebrew of the Law for his audience—soon to be ethnically cleansed. And it was the native tongue of the women and children driven from Jerusalem as a policy of that Law.

Looking back on Ezra, all three artists are innocent of those twentieth-century outbreaks of apartheid, theocracy, and proxy imperialism that must burden our twenty-first-century reading of Ezra’s reading of the Law.

References

Blenkinsopp, Joseph. 1988 Ezra-Nehemiah, Old Testament Library (London: SCM)

Thompson, Thomas L. 1992. Early History of the Israelite People from the Written and Archaeological Sources, Studies in the History of the Ancient Near East 4 (Leiden: Brill)

Commentaries by Allen Dwight Callahan