Psalm 69

A Cry for Deliverance

The Queen Mary Master

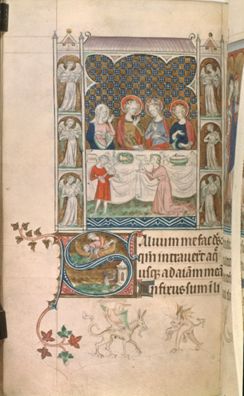

Marriage feast at Cana, with an historiated initial 'S'(alvum) of Jonah being cast from his boat and praying in the sea, with two grotesques battling in the lower margin, from the Queen Mary Psalter, c.1310–20, Tinted drawing, 275 x 175 mm, The British Library, London; Royal MS 2 B VII, fol. 168v, © The British Library Board

In Deep

Commentary by Kathleen Doyle

In England, there was a taste for large-scale illuminated Psalters throughout the Middle Ages. A remarkable example of this is the Queen Mary Psalter, one of the most extensively illustrated biblical manuscripts ever produced, containing around 1000 images. Prefacing, commenting on, and embellishing the Psalms, the illustrations are justly famous for their artistic sophistication in both coloured drawings and paintings.

The manuscript takes its name not from its original owner but from Queen Mary I (reigned 1553–58), to whom it was presented in 1553 by a zealous customs officer, Baldwin Smith, who had prevented its export from England. Although there is no heraldic or documentary evidence that the manuscript’s initial patron was also royal, the magnitude and quality of its illustrations makes an owner of such status very likely. Moreover, its artist—extraordinarily, all of the illustration seems to have been made by the same person—is now known as the ‘Queen Mary Master’ after this book.

Psalm 69 (Psalm 68 in the Vulgate) is illustrated with an image of Jonah in the initial, presumably on account of the Psalm’s vivid evocation of watery danger:

I have come into deep waters,

and the flood sweeps over me. (v.2)

Above it we see a scene from the life of Christ. The Psalter has a cycle of these scenes, beginning with the Annunciation at Psalm 1, and continuing throughout the manuscript. For Psalm 69 the scene is of Christ’s first miracle at the wedding at Cana, with the Virgin featured prominently at table next to Christ: an episode in which prayer is abundantly answered (as the ‘parched’ Psalmist (v.3) hopes his prayer will be too (v.13)).

An even more extensive cycle of figurative decoration is presented in the lower margins, or bas-de-pages, below the Psalter text. This decoration consists of tinted drawings, which are often, as on this page, seemingly unrelated to the text above. Here the image is of two bizarre hybrid creatures fighting, one armed with a club and shield. Collectively, the astonishing breadth and beauty of the drawings and paintings create a moving evocation of the world, both sacred and secular. They are a fitting accompaniment to Psalm 69’s hard-won moments of praise:

I will praise the name of God with a song;

I will magnify him with thanksgiving. …

Let the oppressed see it and be glad;

you who seek God, let your hearts revive. (vv.30, 32)

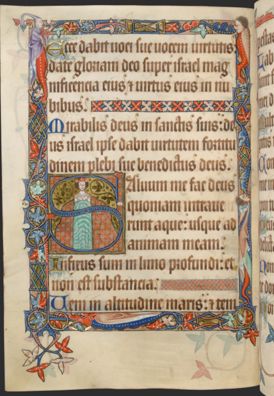

Unknown English artist

Psalm 68; A bearded, crowned king, standing naked in water up to his chest in a shaft sunk into the earth, from The Luttrell Psalter, c.1320–40, Illumination on parchment, 355 x 245 mm, The British Library, London; Add MS 42130, fol. 121v, © The British Library Board Add MS 42130

A Consuming Zeal

Commentary by Kathleen Doyle

The Luttrell Psalter takes its name from a highly prominent inscription, inserted into the biblical text right before the last of the important Psalter divisions of Psalm 109 (in Vulgate numbering). The additional language reads: Gloria patri. D[omi]n[u]s Galfridus louterell me fieri fecit (‘Glory to the Father. Lord Geoffrey Luttrell caused me to be made’). Directly beneath is an image of a man on horseback, whom most scholars identify as Sir Geoffrey himself.

In size, the Psalter is a very large format (355 x 245 mm). It is heavy, too, so it is clear that it was not designed as a hand-held devotional book. Indeed, the Luttrell Psalter would have been much easier to handle (and still is) when placed on a lectern or desk of some sort. The text is large (the smaller letters are about 10 mm high) and is extremely legible, with very few abbreviations. These factors, together with the size of some of the decoration, suggests that the Luttrell Psalter may have been intended for communal reading or use by Sir Geoffrey and his immediate family.

Sir Geoffrey’s book is extensively illustrated, and is particularly known for the rather bizarre hybrid creatures that populate the margins of some of its pages. The full border around the beginning verses of Psalm 69 (Psalm 68 in the Vulgate) includes several such constructs, three with human heads atop sinuous bodies that form part of the decoration. Yet the ornamentation also includes much more straightforward and standardized biblical imagery. In the initial itself, a king, identified by a crown (perhaps king David) stands in deep water, illustrating the first verse: ‘Save me, O God: for the waters are come in even unto my soul’ (v.1 Douay–Rheims).

For another descendant in David’s royal line, the words of this Psalm would seem equally appropriate: the crucified Jesus of Nazareth, given vinegar to drink (v.21); a ‘stranger to his brethren’ (v.8); and altogether ‘consumed’ by his zeal for his Father’s house (v.9).

Jean Mallard [attrib.]

Henry as David kneeling in prayer among ruins, from Henry VIII Psalter, c.1540, Illumination on parchment, 205 x 140 mm, The British Library, London; Royal MS 2 A XVI, fol. 79r, Photo: © The British Library Board

A Davidic King

Commentary by Kathleen Doyle

The illustrations that Henry VIII commissioned in a Psalter for his own use in around 1540 demonstrate that he saw himself as a Davidic king. Henry also annotated the Psalter liberally with marginal notes, commenting on the text. By this date a manuscript Psalter in Latin rather than the more popular Book of Hours was an unusual choice. Perhaps the opportunity presented for a direct alignment with David accounts, in part, for the commissioning of such a personalized copy of this text. The King’s connection with David is made directly in several Psalms, where he appears in the guise of David, wearing a distinctive feathered Tudor hat.

Henry commissioned the Psalter from Jean Mallard, who wrote out the Psalms in a beautifully clear Humanistic script and signed his name in the dedicatory preface as the King’s poet (orator regius). It has never been entirely clear whether Mallard painted the miniatures in the manuscript as well, although it is known that he did illuminate other books, including one for Henry. If Mallard did illustrate some or all of the painting in the Psalter, this may account for the somewhat awkward handling of the perspective and hesitancy in the details in execution of some of the images, as he was primarily a scribe rather than an artist.

In the illustration before Psalm 69 (Psalm 68 in the Vulgate), the King kneels in his armour before an angel of the Lord. The angel holds a scourge in his right hand and brandishes a sword in his left, while cradling a skull against his body. These attributes refer to the choices of punishment offered to David after he had numbered the people of Israel: seven years of famine, fleeing for three months before his enemies, or three days of pestilence (2 Samuel 24:12–14).

No reader of Psalm 69—Henry included—could doubt that to be a Davidic king might mean suffering and trials. But for Henry to kneel and be ‘humbled’ as David was (v.10) was also to hope for the blessing that was David’s:

For God will save Zion

and rebuild the cities of Judah;

and his servants shall dwell there and possess it. (v.35)

The Queen Mary Master :

Marriage feast at Cana, with an historiated initial 'S'(alvum) of Jonah being cast from his boat and praying in the sea, with two grotesques battling in the lower margin, from the Queen Mary Psalter, c.1310–20 , Tinted drawing

Unknown English artist :

Psalm 68; A bearded, crowned king, standing naked in water up to his chest in a shaft sunk into the earth, from The Luttrell Psalter, c.1320–40 , Illumination on parchment

Jean Mallard [attrib.] :

Henry as David kneeling in prayer among ruins, from Henry VIII Psalter, c.1540 , Illumination on parchment

‘Save me, O God!’

Comparative commentary by Kathleen Doyle

The book of Psalms was at the heart of medieval spirituality. Perhaps not surprisingly, therefore, manuscripts containing the Psalms are amongst the most common surviving medieval books. These manuscripts are characterized as Psalters when they also include other texts adding to the book’s devotional character, such as a Calendar, which provided its user with information about saints’ days and other holidays. Typically the Canticles follow the Psalms, together with more localized or personalized prayers and litanies, thereby creating an individualized Christian devotional compilation from a collection of songs originally written in Hebrew and used in the Jewish liturgy.

Like the majority of biblical books in Western Christendom, the texts of these Psalters were written in Latin, in one of the translations traditionally ascribed to St Jerome (d.420 CE), one of the four Fathers of the Western Church. Over a period of nearly twenty-five years Jerome worked on translations of biblical texts from Greek and Hebrew into the Latin vernacular; and is thought to have completed three versions or revisions of the Psalms. Many of these books designed for prayer and devotions, both private and communal, are decorated extensively.

In luxury copies, this decoration often includes ‘historiated’ initials, literally initials with narrative content telling stories. The more ornate letter forms typically occur at the eightfold divisions of the Psalter. These characteristic divisions are derived from the groups of Psalms recited each day (and at Sunday vespers) in monastic practice, and are placed at the beginnings of Psalms 1, 26, 38, 52, 68, 80, 97, and 109 (in Vulgate numbering). Ultimately the groups reflect the requirements of chapter 16 of the Rule formulated by St Benedict (d.547 CE) citing the Psalmist’s reflection that ‘Seven times a day I have given praise to thee’ (Psalm 118:164) and ‘I rose at midnight to give praise to thee’ (Psalm 118:62).

The subjects of these historiated initials became standardized over time, and were generally related either to the life of David, the content of the text itself, or to the Psalm’s heading or title. David’s life is an appropriate subject for illustration because he was believed to be the author of the Psalms. This is the case for the Psalter of Henry VIII, the King’s personal prayer book, in which Henry has himself pictured in the guise of David at several of the important divisions of the book. At the beginning of Psalm 69 (Psalm 68 in the Vulgate) David (Henry) is shown in penitence, in a traditional position of prayer, kneeling, with his hands raised. (Another English example of David in a historiated initial, from the Rutland Psalter, where David is shown as a musician with his harp in the act of composing these Psalms, or sacred songs.)

Another approach is a more literal interpretation of the Psalm text itself. Psalm 69 begins ‘Save me, O God: for the waters are come in even unto my soul’ (v.1 Douay–Rheims). The Psalmist continues with the plea:

Draw me out of the mire, that I may not stick fast: deliver me from them that hate me, and out of the deep waters.

Let not the tempest of water drown me, nor the deep swallow me up. (vv.15–16 Douay–Rheims)

Thus in the Luttrell Psalter, a rather frightened looking naked king is standing in chest-high water, also in a position of supplication.

Another way of illustrating the Psalms was to focus on their allegorical or typological content, drawing on commentaries of the Church Fathers. In the Queen Mary Psalter, for example, the image in the initial is not David but Jonah, who was seen as a ‘type’ or prefiguration of Christ, spending three days in the belly of the whale before being thrown up onto dry land. Moreover, the text of the Psalm is similar in wording to Jonah’s prayer ‘The waters compassed me about even to the soul’ (Jonah 2:6).

For Christian readers, this connection to Jonah would have been part of a more comprehensive set of Christological resonances, for the lines of this Psalm echo powerfully in the New Testament—more, perhaps, than any other except Psalm 22—and mainly in connection with the suffering and death that Jesus, the anointed one (or Messiah), had to undergo. For St Augustine of Hippo there was no doubt: ‘This Psalm sings of the passion of our Lord Jesus Christ’ (In Answer to the Jews 5.6).

The beautiful and captivating images in this exhibition enhance and explicate the text, in each case providing a sophisticated exegesis of this poetic biblical book.

![Henry as David kneeling in prayer among ruins, from Henry VIII Psalter by Jean Mallard [attrib.]](https://images-live.thevcs.org/iiif/2/AW0522_Jean+Mallard+attrib_Henry+as+David+kneeling+in+prayer+among+ruins+from+Henry+VIII+Psalter_royal_ms_2_Cropped2edited.ptif/full/!400,396/0/default.jpg)

Commentaries by Kathleen Doyle