Psalm 72

Long Live the King

Alexander Archipenko

King Solomon, Modelled 1963, cast 1966, Bronze, 67.8 x 28.4 x 28.0 cm, Smithsonian American Art Museum; Gift of Frances Archipenko Gray and Donald H. Karshan, 1968.6, ©️ 2023 Estate of Alexander Archipenko / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York; Photo: Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, DC / Art Resource, NY;

A Leader of Strength

Commentary by Adrianne Rubin

Psalm 72 is an invocation. It asks God to imbue Solomon not only with the virtues of justice and righteousness, but also with an all-encompassing, unending reign in which to ‘defend the cause of the poor of the people, give deliverance to the needy, and crush the oppressor!’ (Psalm 72:4).

Both in its style and its materiality, Alexander Archipenko’s bronze King Solomon is evocative of a monarch capable of ruling with great strength.

King Solomon was the last known sculpture Archipenko modelled, the year before his death. It is thought to be the only sculpture he envisioned being cast on a grand scale, befitting the imposing, regal subject depicted. While this posthumous iteration of the cast is not monumental in size, larger posthumous casts were also made.

Born in Kiev in 1887, Archipenko moved to Paris in 1908 to study. He worked and exhibited alongside the great Modernist artists of the day, including Cubists Pablo Picasso, Georges Braque, and Fernand Léger. Archipenko worked in various media, and he is credited with being among the first Cubist sculptors.

This work, created decades after Cubism first flourished, still exemplifies typical Cubist style. King Solomon comprises—and is reduced to—a series of geometric shapes and seemingly interlocking planes. Multiple perspectives appear to be visible simultaneously. Brilliant in its simplicity, the work renders in abstract form key symbols of the monarch, most notably a crown (as suggested by the two elongated shapes atop Solomon’s head), and regal robes (as implied by the two oversized triangles at the figure’s shoulders). Solomon’s mask-like face may be a nod to the influence of African art upon Cubist style. The overall sharp angularity is reminiscent of Futurist works, which sought to reflect the speed and power of machinery.

Rather than the physical strength implied by Archipenko’s use of bronze, it is King Solomon’s strength of character that is represented in this stark, modern interpretation of the monarch.

References

‘Alexander Archipenko, King Solomon’, Smithsonian American Art Museum, available at https://americanart.si.edu/artwork/king-solomon-552 [accessed 30 December 2021]

‘Alexander Archipenko, King Solomon’, Whitney Museum of American Art, available at https://whitney.org/collection/works/1110 [accessed 30 December 2021]

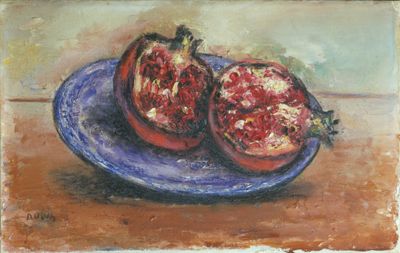

Reuven Rubin

Pomegranates, 1942, Oil on canvas, 22.9 x 35.8 cm, The Jewish Museum, New York; Gift of Ambassador and Mrs. Benson E.L. Timmons III, 1981-20, ©️ Rubin Museum Foundation; Photo by Richard Goodbody, Inc. The Jewish Museum, New York / Art Resource, NY

An Emblem of Righteousness

Commentary by Adrianne Rubin

Let the mountains bear prosperity for the people, and the hills, in righteousness! (Psalm 72:3)

Pomegranates are one of the seven species mentioned in the Hebrew Bible as being native to the Holy Land (Deuteronomy 8:8). They symbolize fertility and plenty, and they are traditionally and aspirationally eaten on Rosh Hashanah, the Jewish New Year, in hopes of prosperity and abundance in the year ahead.

Pomegranates also represent wisdom and righteousness, some of the key attributes most closely associated with King Solomon, and as such, they emblematize Psalm 72. It is worth noting that certain editions of the Bible interpret the latter part of verse 3 as ‘the fruit of righteousness’, lending further credence to this metaphor.

The association of pomegranates with righteousness may derive from the ancient, erroneous belief that each pomegranate contains 613 seeds, the same as the number of mitzvot (commandments)—or righteous deeds—described in the Hebrew Bible. As such, pomegranates have long been a symbol of ‘righteousness, knowledge, and wisdom’ (Stone 2017: 54). So essential is the virtue of righteousness to the author of Psalm 72 that he refers to it four times in the psalm; three of those mentions occur in the first three verses (Psalm 72:1, 2, 3, 7).

Romanian-born, Israeli painter Reuven Rubin featured pomegranates prominently in his extensive body of work. Fascinated by his adopted homeland, the artist felt a visceral connection to the Holy Land of biblical times and often depicted biblical landscapes, folklore, and parables. His 1942 composition Pomegranates evokes both physical and metaphorical aspects of the Holy Land. The vividness of the pomegranate halves and the plate upon which they lie is complemented by the background palette, which calls to mind the desert and the sea. The ambiguous sense of space and perspective combines elements of still life, interior scene, and landscape.

The subject matter and arrangement of Rubin’s Pomegranates can be understood to highlight the notion that the land and the attributes upon which it was built—in large part by King Solomon—are intrinsically bound together.

References

Stone, Damien. 2017. Pomegranate: A Global History (London: Reaktion Books)

Simeon Solomon

King Solomon, c.1874, Egg tempera (?) with touches of varnish on paper mounted to board, 55.9 x 40.6 cm, National Gallery of Art, Washington; Gift of William B. O'Neal, 1995.52.170, Courtesy National Gallery of Art, Washington

A Monarch of Faith

Commentary by Adrianne Rubin

Give the king thy justice, O God, and thy righteousness to the royal son! (Psalm 72:1)

Unlike his father, King David, whose reign was characterized by military might and personal excess, King Solomon was a ruler guided by a redemptive need for justice and righteousness. These are the very qualities the author of Psalm 72 prays Solomon will be imbued with in the psalm’s opening verse.

Simeon Solomon’s c.1874 composition King Solomon highlights the co-existence of the monarch’s political power and religious faith, and it encapsulates specific, diverse influences upon the artist’s life and career up to that point. Born into an Anglo-Jewish family, Simeon Solomon displayed an early interest in biblical subject matter, particularly from the Old Testament (Ferrari and Conroy 2010). Inspired by his artist-siblings, Solomon trained at the Royal Academy in London, where his work would later be exhibited.

This representation of King Solomon reflects the classicist style in which Simeon Solomon was immersed, both during his artistic training and by dint of his affiliation with the Pre-Raphaelites. His preference for classicism, firmly established by the mid-1860s, was further reinforced in those years during multiple trips to Italy, where he was inspired to paint archetypal classical subjects.

King Solomon features certain hallmarks of Renaissance portraiture: lavish, majestic, jewel-toned garb; a profile view (derived from ruler portraits on ancient Greek and Roman coins); and the use of a dark curtain in the immediate background with a landscape vista further afield. The painting also contains stylistic elements contemporary to its day: an overall aestheticized softness; an impressionistic sense of translucency—most apparent in the king’s golden prayer shawl (tallit)—and the seemingly modern throne upon which the monarch sits.

The king’s golden sceptre and helmet are perhaps allusions to ‘gold of Sheba’ (Psalm 72:15). These symbols of material wealth and political dominion contrast poignantly with his golden prayer shawl with its visible fringe (tzitzit), emblems of his religious practice.

Simeon Solomon’s King Solomon portrays a monarch guided by his faith. While the material opulence evident in Solomon’s lavish representation might seem to belie the king’s focus on the lofty ideals of righteousness and justice, the sumptuousness of the composition highlights the trappings of the very faith that undergirded King Solomon’s reign.

References

Ferrari, Roberto C, and Carolyn Conroy. 2010. ‘Simeon Solomon Biography’, Simeon Solomon Research Archive, available at http://www.simeonsolomon.com [accessed 29 December 2021]

Alexander Archipenko :

King Solomon, Modelled 1963, cast 1966 , Bronze

Reuven Rubin :

Pomegranates, 1942 , Oil on canvas

Simeon Solomon :

King Solomon, c.1874 , Egg tempera (?) with touches of varnish on paper mounted to board

The Faith, Strength, and Righteousness of Solomon

Comparative commentary by Adrianne Rubin

Little is definitively known about the authorship of the Psalms as a whole, and Psalm 72, with its puzzling superscription, ‘A Psalm of Solomon’, is no exception. Some interpret this epigraph to indicate Solomon’s authorship, but the more commonly held belief is that Psalm 72 was written by Solomon’s father, David, for his son.

Through the machinations of his mother, Bathsheba, Solomon was enthroned as king during David’s lifetime, bypassing his older brothers in the line of succession. While Robert Alter has argued of the Psalms that ‘the Davidic authorship enshrined in Jewish and Christian tradition has no credible historical grounding’ (Alter 2007: xv), it is tempting to read Psalm 72 both as a ruler’s prayer for his successor and as a father’s prayer for the dynastic reign of his ‘royal son’ (v.1). The idea of David as author seems to be validated further by the Psalm’s postscript as it concludes the second of the five books of Psalms: ‘The prayers of David, the son of Jesse, are ended’ (v.20).

Although David is credited with being the founder of the Judaean dynasty and with uniting the twelve tribes of ancient Israel, his legacy is that of a warrior, and a man of ego and notable moral shortcomings. In marked contrast, redemption, wisdom, righteousness, and the pursuit of justice characterize Solomon. His legacy includes the construction of the First Temple, which took place during his reign. As Alter has written of Psalm 72: ‘This is one of the most magisterial of the royal psalms’ and one befitting the ‘imperial grandeur of the Solomonic reign’ (Alter 2007: 248).

We as readers are invited to join the author in praying for the blessing of life eternal for Solomon:

May he live while the sun endures, and as long as the moon, throughout all generations … May prayer be made for him continually, and blessings invoked for him all the day! (Psalm 72:5, 15)

The three works in this exhibition were selected to reflect a range of interpretations of Psalm 72, all of which centre around King Solomon and the admirable personal attributes to which he aspired and for which he is remembered. We progress from a conventional ‘portrait’ to a more abstract, though still recognisably figurative, representation, to an image used metaphorically.

Simeon Solomon’s late-nineteenth-century study King Solomon highlights aspects of the monarch’s faith, chiefly through the lavish, glistening prayer shawl Solomon wears. The very donning of the liturgical garment is an act of faith, while the concomitant fringes that adorn its four corners are intended to serve as a reminder of God and his commandments. Simeon Solomon, himself Jewish, would undoubtedly have been familiar with the significance and symbolism of this vestment, indicating that its prominence in the portrait was a deliberate, and perhaps a personally resonant, choice.

Alexander Archipenko’s three-dimensional, highly abstracted figurative representation King Solomon contrasts sharply with the elegance of Simeon Solomon’s painted depiction. Archipenko’s sculpture, in its near-minimalist, stark solidity is emblematic of Solomon’s strength. A leader whose power could induce other kings to ‘fall down before him’, Solomon was first and foremost a figure of moral fortitude (Psalm 72:11). A defender of the poor, ‘from oppression and violence he redeems their life; and precious is their blood in his sight’ (v.14). Indeed, it is the strength of Solomon’s moral fibre for which he is remembered, more than his physical or political might.

Unlike Simeon Solomon and Alexander Archipenko’s depictions, Reuven Rubin’s Pomegranates bears no overt relationship to King Solomon. Rather, it lends itself to an entirely allegorical interpretation of righteousness, one of the symbolic associations of the fruit, and a key attribute ascribed to the monarch. Righteousness features prominently in Psalm 72. Pomegranate-shaped finials often cover the wooden handles of Torah scrolls, indicating how revered and fundamental their symbolism is in Judaism. As Damian Stone has discussed: ‘King Solomon is in fact alleged to have designed his crown based on the crown-like calyx of the pomegranate’ (Stone 2017: 56). Moreover, countless pomegranates were said to embellish the architecture of Solomon’s Temple (ibid 56). Rubin’s Pomegranates, with its subtle visual allusions to the desert and the sea, serves as a latter-day emblem of Solomon and the kingdom he helped to create, rule, and define.

Seen together, these three works illustrate the legacy of King Solomon and the timeless poetry of Psalm 72.

References

Alter, Robert. 2007. The Book of Psalms: A Translation with Commentary (New York: Norton & Company)

Stone, Damien. 2017. Pomegranate: A Global History (London: Reaktion Books)

Commentaries by Adrianne Rubin