Proverbs 4

Get Wisdom

Giorgio Andreotta Calò

Anastasis (άνάστασις), 2018, Light installation, Installation view, Oude Kerk, Amsterdam; Photo by Gert Jan va Rooij, Courtesy the artist and Oude Kerk

The Light of Dawn

Commentary by Lieke Wijnia

Founded around 1213 and consecrated in 1306, the Oude Kerk (Old Church) in Amsterdam has undergone many changes to its appearance throughout its existence. Most dramatically, during the iconoclastic fury of 1566, statues were removed or demolished and frescoes were overpainted.

Seeing the Oude Kerk as it appears today, ‘empty’ and devoid of decorations, contemporary Italian artist Giorgio Andreotta Calò (b.1979), accustomed to Catholic church interiors, could hardly believe it was still functioning as a living place of worship. Between 25 May and 23 September 2018, he created an installation alluding to the once-present images in the building. Titled Anastasis (Greek for ‘resurrection’), his work sought to explore what the effect of the return of these lost images (as though ‘from the dead’) would be (Oude Kerk 2018).

Anastasis was a temporary exhibition, in which all of the church windows were covered with red foil, and following which a semi-permanent installation in the Holy Sepulchre chapel replaced the clear window glass with coloured red glass. This chapel once housed a sculpture of the Entombment under its baldachin: a reminder of Christ’s Passion and of the blood shed on the cross. Calò’s red light alludes to this sculpture’s ‘presence’: once physical, now virtual in the eucharistic rituals which continue in the church.

The red light also evokes a photographer’s developing room, in the phase where captured images have not yet appeared on paper. Such images are as ‘in between’ as they are in the Oude Kerk: present and not present at the same time. In fact, during the exhibition period, the church literally functioned as a developing room for photographic prints Calò made of the only surviving pre-Reformation stained-glass window (Oude Kerk 2018).

Proverbs does not refer to particular nations or faith communities. There is a universalism to its use of light as a metaphor for developing wisdom (‘the course of the righteous is like morning light, growing brighter till it is broad day’; v.18).

Though its title draws from Greek Orthodoxy, Anastasis reflects this universalism, as ‘resurrection’ is translated into a more general visual language of light. By changing the light, Calò encouraged visitors of all backgrounds, whatever their particular experiences and quests, to transform their perceptions of what was in front of them (and what was once there but no longer). To see things in a different light.

References

Oude Kerk. 2018. ‘Giorgio Andreotta Calò–Anastasis’, www.oudekerk.nl, available at https://oudekerk.nl/en/programma/giorgio-andreotta-calo/ [accessed 25 January 2020]

Hendrik Valkenburg

Edifying Hour in the Achterhoek , 1883, Oil on canvas, 133.5 x 204 cm, Museum Catharijneconvent, Utrecht; RMCC s370, Courtesy of the Museum Catharijneconvent

The Right Inheritance

Commentary by Lieke Wijnia

In the nineteenth century, barn services were a frequent phenomenon in the Dutch countryside. Taking place in either the barn or another part of a farm building, the painter Hendrik Valkenburg (1826–96) harboured a longstanding wish to paint one.

It is likely that the group we see gathered in Edifying Hour in the Achterhoek is listening to a practitioner, who, walking a separate path from the official Protestant church, had a strict focus on—and an exemplary knowledge of—the Word (Kootte 2019). The practitioner is the Christian embodiment of the first verses of Proverbs 4, demanding attention for his teachings: ‘Hear, O sons, a father’s instruction, and be attentive, that you may gain insight; for I give you good precepts: do not forsake my teaching’ (vv.1–2).

Traditional settings for worship (framed by solemn but grand church architecture) have been replaced here by what seems to be the kitchen area in a modest farm house, with hay on the floor and smells that can only be imagined. Several elderly and young mothers are seated, while other participants in this service are standing at the back or leaning on the furnace. Instead of a psalm board (frequently hung at the front of a church to display the psalms that would be sung or recited by the congregation), a similarly shaped wooden board with a display of spoons hangs on the wall, underscoring the homely character of this scene.

One of this work’s concerns is the honouring of tradition, and a very particular idea of what this tradition entails is evident here. For this particular religious congregation, it means valuing the fundamental role of Scripture in their lives.

It may seem remarkable, then, that the painting won a gold medal in that showcase of progress, the World Exhibition of 1883 in Amsterdam. At such exhibitions, participating nations tended to display their most state-of-the-art technology and their most innovative art and design. At the Amsterdam World Exhibition, the Netherlands presented amongst other things this prize-winning painting, and it was immediately sold to a collector.

Whereas elsewhere in Europe, and particularly in France, the Impressionist style of painting was trending, this work embodies a wholehearted appreciation of a distinctly traditional approach to Protestantism. In the context of an international occasion of nationalist display, the Dutch publicly self-identified with a God-fearing, instruction-taking group of people—like the addressees of Proverbs 4.

References

Kootte, Tanja. 2019. ‘Een Stichtelijk Uurtje, 6 January 2019’, www.artway.eu [accessed 24 January 2020]

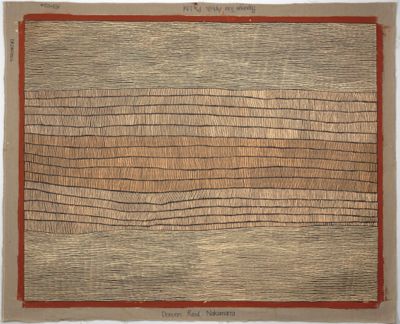

Doreen Reid Nakamarra

Marrapinti, 2008, Acrylic on canvas, 122 x 153 cm, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; Gift of Robert Kaplan and Margaret Levi, 2017, 2017.251.2, © Estate of Doreen Reid Nakamarra, licensed by Aboriginal Artists Agency Ltd; Photography: Spike Mafford

Embodied Wisdom

Commentary by Lieke Wijnia

In Australian Aboriginal culture, to explore and know the land and its history is also to know oneself, one’s community, and its resources (Morphy & Carty 2015: 45–6). Purposeful movement is an important element in this active relationship, requiring both expertise and care for the pluriform layers of historical, natural, and spiritual meaning in walked landscapes. This embodied approach to knowledge of oneself and one’s surroundings is passed on from one generation to the next.

Such an approach is also reflected in the final verses of Proverbs 4.

Although the text’s fatherly advice is not addressed to daughters, women feature at various moments in Proverbs. Chapter 4 mentions the father’s mother (v.3) and includes the metaphorical figure of Wisdom as a woman (vv.6–9).

And this painting by Doreen Reid Nakamarra evokes the paths taken by ancestral women to a significant sacred site (Marrapinti Rock Hole), where they would camp. Its visual texture and the delicacy of its shading give it a radiant quality. In this way it reinforces the experiential and spiritual aspects of the women’s journey, which only emerge as experience and wisdom grow.

Wisdom ultimately resides in the heart, as Proverbs 4 states several times (vv.4, 21, 23). For the ancient communities who compiled Proverbs, the heart was regarded as the seat of intelligence and will, rather than of emotion (Whybray 1972: 33; Hunter 2006: 87–8). But (I would argue) for those who travel in the spirit of Reid Nakamarra’s women, the heart is an effective compass because it is a site of both intelligence and intuition.

Reid Nakamarra’s painting not only reflects the travels of the ancestral women, but also their remembrance and thus the significance of oral traditions and rites of passage through which knowledge (wisdom) is gained. The story of the painting belongs to Reid Nakamarra’s husband’s people, which Reid Nakamarra was only allowed to paint after she had been part of the community for a certain length of time (Cirigliano 2017). Wisdom requires growth over time. It is only with age and embodied experience that one is able to follow in ancestral footsteps (Morphy 2013: 100). The instruction ‘Look out for the path that your feet must take, and your ways will be secure’ (Proverbs 4:26) resonates here.

This artwork, like the book of Proverbs, illuminates our place on the bridge between ancestral pasts and spiritual presents.

References

Cirigliano II, Michael. 2017. ‘Curator Conversations: Exploring Contemporary Aboriginal Art with Maia Nuku’, 25 October 2017’, www.metmuseum.org [accessed 25 January 2020]

Hunter, Alastair. 2006. Wisdom Literature (London: SCM Press)

Morphy, Howard. 2013 [1998]. Aboriginal Art (London: Phaidon)

Morphy, Howard, and John Carty. 2015. ‘Understanding Country’, in Indigenous Australia, Enduring Civilisation (London: The British Museum), pp. 20–119.

Whybray, Roger Norman. 1972. The Cambridge Bible Commentary on the New English Bible: The Book of Proverbs (London: Cambridge University Press)

Giorgio Andreotta Calò :

Anastasis (άνάστασις), 2018 , Light installation

Hendrik Valkenburg :

Edifying Hour in the Achterhoek , 1883 , Oil on canvas

Doreen Reid Nakamarra :

Marrapinti, 2008 , Acrylic on canvas

Fatherly Advice

Comparative commentary by Lieke Wijnia

Within the larger structure of the book of Proverbs, chapters 1–9 have a particular place. Formulating the importance of a fearful or awe-inspired relation to God, their tone is distinct. And although, as seems likely, Proverbs’ first nine chapters were written last, they were placed first, to set the tone for the entire book (Whybray 1972: 14; Hunter 2006: 80).

Simultaneously, these first chapters show their indebtedness to eastern wisdom traditions. Forms of Egyptian didactic instruction provide Proverbs 4 with its model: a father sharing his wisdom with his son—at times literally using the term ‘instruction’ (vv.1, 13)—about what it means to live a righteous and meaningful life (Whybray 1972: 4).

While the father’s instructions distinguish very clearly between the righteous and the wicked, the light and the dark (vv.18–19), the son is also encouraged to live his life and discover the world on his own. The father evokes the fact that instruction is simultaneously inherited and passed on—a gift he received from his own father (vv.3–4) as well as a gift he bestows on his son (vv.11–12). This key message is developed in the three blocks of verses. Each of these three blocks has a distinct approach to (the instruction of) wisdom (Whybray 1972: 29–32).

The first notion is to cherish the value of inherited wisdom. In his 1883 painting, Hendrik Valkenburg depicts a group valuing their perception of the righteous inheritance during a service in the rural Achterhoek area in the east of the Netherlands. Dissatisfied with Protestant ministers who were, in their eyes, too free-spirited, several secessionist groups began organizing services in barns throughout the nineteenth century. The group portrayed here—probably consisting of such secessionists—spans various generations, with even the smallest child sitting on the floor leafing through a picture Bible.

Reinforcing the centrality of Scripture for this group, the notion of fatherly advice is enacted by the practitioner who leads the service, a clergyman not distracted by institutional politics but entirely focused on the Word. Holy Writ is the locus of wisdom for these devotees. He and his listeners together embody the view that institutions had corrupted the value of traditional wisdom and sought to re-pave the right path on their own.

The fatherly instructions of Proverbs very clearly envision what this right path consists of and how it stands out from the ‘wicked’ path of temptation and darkness. Only through gaining wisdom and obtaining insight will the son be able to recognize this distinction in the wider world (vv.14–15,18–19). While these instructions function on a more theoretical level, the actual living of life will offer a more practical test, demanding of the son an ability to see the difference between right and wrong, and to resist temptation.

The notion of gaining and applying wisdom, and discovering how it makes one see the world differently, can be recognized in the 2018 installation by Giorgio Andreotta Calò. He transformed the famous fall of light in the Oude Kerk in Amsterdam by applying red foil to all the church windows. With this one simple intervention, he completely altered the way that visitors to the church saw the interior of the building. The installation challenged visitors to adapt their eyes (and minds) to perceive anew an environment they might have thought they knew well. Likewise, so Proverbs teaches, wisdom imbues our surroundings, but we have to undergo (trans)formation in order to discern it.

In addition to its instructions about resisting external temptation, the last part of Proverbs 4 reinforces the internal challenges the son will face. The father’s teachings about how to deal with this draw on deep ancestral wisdom. Doreen Reid Nakamarra’s 2008 painting likewise focusses on the wisdom of ancestors as it represents the journey of a group of women to an Aboriginal sacred site. Wisdom is gained through knowing and re-encountering the ancient spirituality of the land, or (as Aboriginals call it) ‘country’.

Such a journey can only successfully be made by attending to one’s embodied presence in the ‘country’ that is travelled; the land in which spiritual ancestors are embedded.

Proverbs 4 speaks a great deal about bodies. The heart, ear, feet, eyes, and flesh are vessels of wisdom in finding the right path. Thus, Reid Nakamarra’s painting also brings us back to a theme of Valkenburg’s work. Despite the vast post-colonial impact on Aboriginal traditions, one of the remaining, defining features of Aboriginal culture is the value of orally and ritually transmitted knowledge (or, indeed, wisdom) from generation to generation, from—to speak with Proverbs 4—father to son.

References

Hunter, Alastair. 2006. Wisdom Literature (London: SCM Press)

Whybray, Roger Norman. 1972. The Cambridge Bible Commentary on the New English Bible: The Book of Proverbs (London: Cambridge University Press)

Commentaries by Lieke Wijnia