Proverbs 8

Whoever Finds Me Finds Life

Tom Denny

The Wisdom Window, 2012, Stained glass, The Chapel, St Catherine's College, Cambridge ; © Thomas Denny; Photography by James O. Davies

The Road to Wisdom

Commentary by Hilary Davies

In the right hand light of Thomas Denny’s stained-glass window the female figure of Wisdom emerges from the shadows to take ‘her stand beside the gates in front of the town’ (v.3). In a tender gesture that evokes Proverbs 3:16 (‘Long life is in her right hand; | in her left hand are riches and honour’) she greets the seeker, who prepares not so much to leave the city as to enter upon a life pilgrimage that evolves upwards. Beyond the foliage, pediment, and coat of arms—allusions to the architecture of St Catharine’s College—the landscape is a visionary one. It is lit by glowing pinks and ambers that link it to the pilgrim; talking figures move along a path which becomes a river, finally losing itself in a sea transfigured by a bright pale moon and stars.

The left hand light of the window echoes this theme of imparted knowledge and revelatory wisdom. An older, balding man engages a younger in conversation; they could be father and son, tutor and student; what matters is the passing on of the eternal, whispered truths. The young man carries a staff: he too is set upon a winding road that threads past the pollarded willows and water meadows of Cambridge in a deep pool of blue, counterbalancing the warm lights on the other side. The top panel promises the radiance of the setting sun. The iconography of Denny’s windows is inlaid with the local landscape to remind us that the Christian spiritual life can only be fulfilled through the accidents of our everyday and personal histories.

Rising up through the centre of the window are the tall trunk and spiky crown of an all-embracing tree, sheltering the searchers after knowledge and wisdom below; even the little dog thrusting his muzzle towards the young man at the gate of life is not left out. The tree’s top is in the firmament, its roots amongst bright stones and cobbles that show us how Wisdom transforms all, even base earth: ‘My fruit is better than gold, even fine gold, and my yield than choice silver’ (v.19).

Mary S. Watts

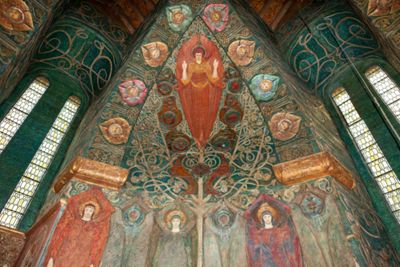

The Tree of Life, interior of the Watts Cemetery Chapel, 1898, Coloured plaster, Watts Cemetery Chapel, Compton, Surrey, UK; AC Manley / Alamy Stock Photo

I was Beside Him like a Master Worker

Commentary by Hilary Davies

On a little knoll, hidden away in the rolling woodland of the Surrey Hills, stands a chapel like no other in the world. It arrests by the bright ochre red of its bricks and tiles, which seem to cast a Tuscan light on the graveyard that surrounds it. Yet it also confuses the eye as it does not conform to any familiar ecclesiastical architectural template. Around its midriff runs a richly decorated frieze, a syncretic riot of motifs from Christian Celtic, Romanesque, Gothic, and Byzantine sources as well as Scandinavian, Egyptian, and Indian iconography. Inside, the structure is bejeweled from floor to ceiling with vines, birds, flowers, angels, stars, suns, moons, and images of human and divine spiritual life. Four seraphs, (one of which is shown here) tower in the tree of creation, hands raised to bless God’s work in the manner of both the Eastern and Western churches (Bills 2010: 60).

This is the vision of the artist, designer, and potter, Mary Watts: a vision that quite literally incarnates her Christian faith. After moving to Compton with her husband, the symbolist artist, G. F. Watts, she discovered a seam of gault clay in the area. This enabled her to realize her dream of constructing a chapel of ease for the local villagers, to help them in their grief; and in so doing, she wished to train those very villagers to adorn their own building and make it a hymn to God’s creation. The local blacksmith and wheelwright, the women and children, learned how to impress patterns, to mould and paint gesso, to forge and carve the symbols of eternity (Watts 2012). Rarely has John Ruskin’s communitarian project of combining labour with joy been so perfectly achieved (Ruskin 1892: 17–18).

On the outside, the frieze that runs like a hoop holding the elements together visually and theologically is the ‘Path of the Just’, upheld by corbels representing the Way, the Truth, and the Life. ‘The Spirit of Truth’ panel lies on the southwest side, the direction of the fructifying zephyr. Angelic profiles pore over the symbols of wisdom: the owl of Athene, the key of knowledge, the maze of pilgrimage, the sun of enlightenment, and the cross of salvation. This is the way the chapel urges us to go: ‘I walk in the way of righteousness, along the paths of justice’ (v.20).

References

Bills, Mark. 2010. Watts Chapel: A Guide to the Symbols of Mary Watts’s Arts and Crafts Masterpiece (London: Philip Wilson)

Ruskin, John. 1892. ‘The Nature of Gothic’, in The Stones of Venice (London: G. Allen)

Watts, Mary Seton. 2012. The Word in the Pattern (1905): Facsimile with Accompanying Essays on Mary Watts’s Cemetery Chapel, Drawn from the Watts Gallery Symposium 2010 (Lymington: Society of Art and Crafts Movement in Surrey)

Paul B. Kincaid

Memorial for Corporal Bombardier Samuel Robinson, 2014, Sandstone, Collection of Dennis and Alison Robinson; © Paul Kincaid

My Cry is to All That Live

Commentary by Hilary Davies

Wisdom says ‘My cry is to all that live’ (Proverbs 8:4): but who are the living and what does it mean to have life?

In the Ancient Near East, the gates of a city were massive, double entranced defensive constructions that were also the site of major transactions (May 2014: 88ff). Here the king offered audiences, dispensed justice, and oversaw the preparations for, and outcomes of, war—thinking to demonstrate in this last respect how effective he was as the protector of his people. Despite the exterminatory capacities of modern warfare, political leaders in many parts of the world still pander to such a view; young men, whole populations, die as a result. Now, as always, such conflicts will be the result of the pride, arrogance, and ‘perverted speech’ (v.13) against which Wisdom rails.

The figure in Paul Kincaid’s Memorial to Samuel Robinson, a soldier killed at the age of 31 in Afghanistan, opens its arms in an imploring gesture: it is the gesture of all parents who have been thus bereaved as they wail for their dead sons. The outstretched stumps are also prophetic: wanton waste of life is what results from the lack of wisdom on the part of those who do not ‘govern rightly’ (v.16), those who, hating Wisdom, are in love with death.

Wisdom’s words, however, concern more than wise and just governance. She repeatedly offers riches and wealth (vv.18, 21), yet this is not merely filling our treasuries or investment portfolios. The wealth she promises is life itself, life in the life of the Lord. It is a life that transcends the boundaries of time, there before the world was created and, by implication, there after it ends, although Wisdom does not explicitly say so. This terrifying mystery, the paradox of time and eternity, moves at the heart of Kincaid’s sculpture. At the top of the supporting trunk sit two ovular shapes, the eggs of fertility and regeneration, and at this horizontal they meet the downturned beak of the dove, the Holy Spirit, the intercessor-paraclete, the angel of life and death, whose wings and feathered tail, we now see, are the mutilated limbs and faceless head of grief.

References

May, Natalie N. 2013. ‘City Gates and their Functions in Mesopotamia and Ancient Israel’, in The Fabric of Cities: Aspects of Urbanism, Urban Topography and Society in Mesopotamia, Greece and Rome, ed. by Natalie N. May and Ulrike Steinert (Leiden/Boston: Brill), pp. 77–122

Tom Denny :

The Wisdom Window, 2012 , Stained glass

Mary S. Watts :

The Tree of Life, interior of the Watts Cemetery Chapel, 1898 , Coloured plaster

Paul B. Kincaid :

Memorial for Corporal Bombardier Samuel Robinson, 2014 , Sandstone

The Circle of Eternity

Comparative commentary by Hilary Davies

Proverbs 8 is a passage dense with symbolism and rich interpretations, a text about creation and growth, metamorphosis and rites of passage, self-awareness and responsibility. It carries precepts for how we should live with others and offers an epiphanic vision of the works of God.

We find here some of the most famous and beautiful poetry in the Old Testament. This is in part because of the images and cadences which have resonated down the centuries in many languages, but also because of other theologically important associations: the creation narrative in the first chapter of Genesis; the prologue that introduces the Word in John 1:1–5; Christ’s assertion in John 8:58, ‘Before Abraham was, I am’; and His prayer as He takes leave of His disciples at the Last Supper, ‘So now, Father, glorify me in your own presence with the glory that I had in your presence before the world existed’ (John 17:5). All these texts stress the all-encompassing nature of God’s living presence, just as Wisdom is there before the beginning of creation; they also tell us that God stands in a completely different relationship to time from that of the created universe.

In Proverbs 8:1–21, Wisdom exhorts the people to learn from her. The pearls she offers here concern human society; by tradition prophets stood at the gates to exhort their populations to repent of sin or to warn of danger. This was the public seat both of civic government and of the spiritual life, so Wisdom has placed herself right at the moral pulse of the nation. But there is more. She is the moral pulse of the nation. Not to follow her is to reveal oneself as a vassal to evil, since from her derives the righteous behaviour which is the hallmark of walking with God (Proverbs 16:6; Daniel 2:20–2).

Thomas Denny’s Wisdom Window explores the organic nature of this process through the imagery of pilgrimage. Youth and age converse with each other in a landscape marked by the gateways, meandering paths, and flowing water emblematic of our traversal of life in time, yet all move upwards towards a representation of the transcendent cosmos by which we are contained and transformed. The crossbars of the window both remind us of Christ’s cross and support the great branches of the sheltering tree of life that is Christ Himself.

In the Christian era, Wisdom’s great paean to God in Proverbs 8:22–36 has sometimes given rise to controversy. The Arian schismatics claimed it showed that Christ, so often identified with Wisdom, was a creature, not begotten. It was a view that did not prevail, in large part because the effect of stressing this is to separate God from his creation. And central to Christianity is the belief in the incarnate God, the God who participates in creation, suffering with it and redeeming it. Paul Kincaid embodies this notion in his Memorial: there is no greater challenge to humanity’s idea of self than death. Kincaid’s figure fuses lament and solace, absence and presence, body and spirit; it, too, forms the tree of the rood, a body that carries the poignant vigour of dead youth in its musculature, yet receiving from above the delicate breath of the Holy Spirit, the person of the Trinity synonymous with hope. The figure’s arms, even though stunted—and in this they symbolise Christ’s assumption of our own flesh and blood—are flung wide to reach all points of the compass and embrace all creation. They form ‘the circle of eternity with the cross of faith running through it’.

This last phrase is Mary Watts’ own formulation of what she was trying to achieve in her mortuary chapel (Watts 2012: 4). Her temple to heaven and earth is literally made out of the soil on which it stands: it is itself a tree of life. Its floor plan is the square Greek cross superimposed upon the wheel of the universe. Exterior and interior decoration reach from the tiniest wildflowers of the meadow to the thunderous figures of the four seraphs, embodiments of knowledge and ardour for God, towering over space and time. This is Watts’s homage to Wisdom’s vision of God calling creation into being,

When he established the heavens, I was there;

When he drew a circle on the face of the deep

… then I was beside him, like a master worker

… rejoicing in his inhabited world

and delighting in the human race. (vv.27, 30–31)

References

Watts, Mary Seton. 2012. The Word in the Pattern (1905): Facsimile with Accompanying Essays on Mary Watts’s Cemetery Chapel, Drawn from the Watts Gallery Symposium 2010 (Lymington: Society of Art and Crafts Movement in Surrey)

Commentaries by Hilary Davies