Proverbs 9

Wisdom and Folly

Sabelo Mlangeni

Invisible Woman II, from the series 'Invisible Women', 2006, Gelatin silver print, 23.3 x 34.6 cm (image); 26.2 x 37.5 cm (paper), The Art Institute of Chicago; Restricted gift of Pamela J. Joyner and Alfred J. Giuffrida, 2016.32b, ©️ Sabelo Mlangeni; Courtesy of the artist and blank projects. Photo: The Art Institute of Chicago / Art Resource, NY

A Ghost

Commentary by Rozelle Robson Bosch

Who is this ghost that sweeps the city of Johannesburg’s streets in the middle of the night? Through his camera lens, Sabelo Mlangeni posed this question in the 2006 exhibition Invisible Women.

She comes out when all have gone in. She is a woman of the night. But such women come in many forms. So, the anonymous woman known to us only in her obscurity signals a question: ‘what do we see when we look at her?’ Mlangeni does not fully reveal what he saw when he took the photograph. He undertakes a visual ‘veiling’ that alters the agenda of the photo, rendering open and unscripted the story told by the ‘invisible’ woman of his title.

Various artists (for example, Mlangeni’s fellow South African Pieter Hugo) have used black-and-white photography to evoke a voyeuristic gaze which exposes its subjects to uninvited inspection. But not in this instance. The movement in this photo, and its blurring of contours, rebuff any attempt we might make to know this woman. She will not be demystified.

And yet the photo also suggests an impending immediacy of presence. In the dialectic of nearness and distance at play here, Mlangeni collapses the space between the onlooker and the woman. Virtually nothing is shown of the road that separates her from us; we see only a thin strip beneath the steep drop of the kerb. It is as though she approaches the front of a stage, presaging imminent contact with the watching audience, and with it our possible transformation through a direct relationship with her (in contrast with the voyeur, who stays hidden).

In Proverbs 9, two different invitations can be heard in the city streets. Both invitations ask the hearer to turn aside (vv.4, 16) and see something new. But only one of these invitations (uttered by Wisdom’s ‘maids’; v.3) leads to a genuine metamorphosis: from ‘simpleness’ to ‘insight’ (v.6).

As a transformative presence in the nocturnal city, the woman in Mlangeni’s photograph also signals metamorphosis: whether of the dirty urban space becoming clean, the invisible becoming visible, a ghostly apparition becoming angelic—or (perhaps through her agency) ourselves becoming, somehow, wiser.

Herein lies Invisible Woman II’s most striking feature: she is draped in metaphors; enigmatic but engaging; issuing an open-ended challenge to the ways in which we look; and asking what our ways of looking allow us to see.

References

Mlangeni, Sabelo. 2007. Invisible Women, Warren Siebrits Modern and Contemporary Art Catalogues 26 (Johannesburg: Warren Siebrits)

Mwangi Hutter

Turquoise Realm, 2014, 3-channel video, 8:45 min loop; ©️ Mwangi Hutter; Courtesy of the artist

A Transfiguration

Commentary by Rozelle Robson Bosch

In 2014, the artist duo Mwangi Hutter made the three-channel film Turquoise Realm, in which they also perform. Initially, they are framed in separate projections, the woman on the left and the man on the right, each lying naked and alone on their bed. The woman then appears in the man’s space, lifting him onto her lap and subsequently carrying him out of the frame as though towards the central ‘room’. We next see them lying together on the bed in the central projection, before they merge and are replaced by (are perhaps transformed into) a mound of fruit and flowers. In the final seconds, we glimpse them lying down again in the spaces opposite those in which they began, but the fruit and flowers remain.

The intimacy of the film’s two subjects—the reciprocity which overcomes the divide between ‘self’ and ‘other’—becomes an offering of intimacy to the viewer as well. We are invited not just to look at the work but participate in it—to imagine our own offering, whether inspired by the initiating strength of the woman or by the trusting reliance of the man. In meditating on the work, we may come to know—and give—ourselves better.

Such self-offering can be conceived as a sort of piety. It is a piety that in this film issues in what might be read as blessing: it ‘flowers’, and the bed in the central projection becomes like a banquet. ‘Wisdom … has set her table’ (Proverbs 9:1–2).

The work evokes piety in another way also. Its tripartite structure recalls the tradition of constructing Christian altarpieces in the form of three (usually painted) panels.

Traditionally, the central panel is the focal point to which the flanking panels are subordinate. Turquoise Realm, it may be argued, is no different. The centre is the site of a consummation. It is preceded by Mwangi’s pause as she holds Hutter in the position of a Pietà, and by an intensification of sunlight which seems to drench their bodies.

On the Christian altars above which triptychs stand, both sacrifice (Christ’s offered body) and glory (Christ’s transfigured, resurrection body) are recalled and made present, and the bodies of participants in turn are invited to share in both Christ’s sacrifice and his glory.

In Turquoise Realm, comparably, Mwangi Hutter’s offered bodies become transfigured bodies, in an event of communion which issues in a feast.

References

Brown, Will A. 2014. ‘Mwangi Hutter Interview: “We are interested in Personal and Universal Responsibility”’, www.studiointernational.com

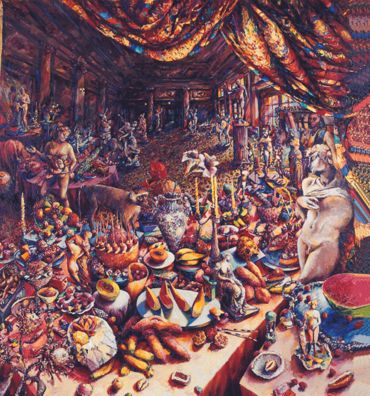

Penny Siopis

Melancholia, 1986, Oil on canvas, 197.5 x 175.5 cm, Johannesburg Art Gallery; ©️ Penny Siopis, Stevenson Cape Town

A Banquet

Commentary by Rozelle Robson Bosch

This painting is an assault on the gaze of the viewer.

The work’s immediate foreground beckons us to delight in the vividly decadent depiction of a banquet. By the time our gaze has penetrated further, however, the banquet has taken a turn for the worse. The malaise of grotesque wastefulness that awaits us in its depths redefines all our initial perceptions. The monkey, the over-ripe fruit, and the critical regard of the artist who depicts herself at the right, meeting our eyes as though to challenge us, signal that this banquet is stale, surreal, full of the vestiges of misaligned desires.

With a self-consciously postmodern relish for the play of surfaces and simulacra, Melancholia stylistically echoes baroque art, but it also subverts its ambitions and its entanglement with the aesthetic history of colonialist Western powers. Baroque art continued the High Renaissance’s celebration of both dynamic movement and fervent emotion, while displaying an increasing fascination with the solidity and grandeur of objects, architectural spaces, and the human form (Chilvers 2004: 52–53). Melancholia successfully reiterates (‘quotes’) the main characteristics of this style while simultaneously offering a critique of it: a critique of the power and importance of possessions as cultural artefacts, and of the human body as commodity.

In this, it has much in common with Proverbs 9, which likewise presents us in quick succession both with a familiar trope and its subversion. A feast and the parody of a feast are described, one after the other—each presided over by a female figure (just as Siopis presides over the banquet in her painting). Both Proverbs and the painting challenge us to choose.

Even in her method, Siopis challenges us. In the unusually energetic layering, pasting, and physical blending of her paint upon application, she gestures to the material nature of existence; its carnality. She acknowledges the fleshly parameters that define all bodies. She knows these are attractive. But they are also deceptive. The relationship between the body’s surface and its depths means that it can present itself as intact even when hiding an abyss of suffering or corruption (NLA 2013). The onlookers’ gaze is drawn to the former and subverted by the latter. Consumptive desire is brought up against the possibility of a false satiation. The ‘spoils’ of acquisitiveness and indulgence spoil.

Siopis’s formidable banquet, like that of Folly, is not meant for feasting (Nuttall 2011: 289–98).

References

Chilvers, Ian (ed.). 2004. ‘Baroque’, in The Oxford Dictionary of Art, New edn (Oxford: Oxford University Press), pp. 52–53

NLA Design and Visual Arts. 2013. ‘Penny Siopis: NLA Design and Visual Arts: Visual Literacy’, available at https://nladesignvisual.wordpress.com/2013/08/03/penny-siopis/ [accessed 10 March 2023]

Nuttall, Sarah., 2011. ‘Penny Siopis’s Scripted Bodies and the Limits of Alterity’, Social Dynamics, 37.2: 289–98

Sabelo Mlangeni :

Invisible Woman II, from the series 'Invisible Women', 2006 , Gelatin silver print

Mwangi Hutter :

Turquoise Realm, 2014 , 3-channel video, 8:45 min loop

Penny Siopis :

Melancholia, 1986 , Oil on canvas

The Beginning of Wisdom

Comparative commentary by Rozelle Robson Bosch

Looking may not always equate with seeing. The art critic Roger Fry, writing in 1919, discussed the difference. Seeing, he said, is a useful skill that nature has given us. It has to do with the use that appearances have for the business of living. In other words, it is functional. We extract key information as rapidly as possible from this kind of seeing. It tells whether the movement in the long grass is the wind or a tiger about to pounce; whether the Gucci handbag is real or a fake; and whether the bread has gone mouldy.

Looking, on the other hand, seems less obviously to have any utility value. It is what discerning viewers of art do, and the non-utilitarian character of such looking leads Fry to say that ‘biologically speaking, art is a blasphemy’, because it serves no obvious purpose. Looking is something like an act of devotion (Fry calls it ‘passion’; 1923: 47–48).

In the terms of Proverbs 9, a parallel comparison might be made between ‘simpleness’ and ‘insight’ (v.6). The simple-minded may ‘see’ without really ‘looking’; but it is only the attentiveness of looking that leads to the discovery of what Proverbs calls Wisdom. Moses found this when he first saw the burning bush, then actively turned aside to really look at it (Exodus 3:2–3). The reward was ‘knowledge of the Holy One’ (Proverbs 9:10). Lady Wisdom calls for a similar response (and offers the same reward) with her cry ‘turn in here!’ (v.4).

But Proverbs 9 complicates Fry’s distinction between utilitarian ‘seeing’ and non-utilitarian (passionate) ‘looking’. Like much of the Bible’s so-called ‘Wisdom’ literature, it teaches that for everyday, ordinary life to be flourishing life, we need both the efficiency of quick sight and the depth of devoted insight. Wisdom is no optional extra, even in the most mundane and practical contexts.

Each artwork in this exhibition asks us to pursue insight. In Penny Siopis’s Melancholia, the superficial appearance of a banquet becomes in its detail an exposé of our misaligned desires. Mwangi Hutter’s Turquoise Realm transforms the interaction of bodies into a sacramental sign of how self-giving can bear fruit in unexpected abundance. In Sabelo Mlangeni’s Invisible Women II, a nocturnal apparition emerges towards us from out of the darkness and we are challenged to turn aside and make something of her—finding, as we do so, that a spotlight has been turned on ourselves too. All three instances call us to turn aside. All three invite the participation of our gaze. All three threaten to change us in one way or another (perhaps, if we really look, by directing us toward Wisdom).

Lady Wisdom reflects the search of a post-exilic community of faith for God’s face in the everydayness of life. Possibly composed for use within a liturgical celebration (Sinnott 2005: 86), this passage in Proverbs portrays her as an embodiment of God’s worldly presence. But she is also elusive—like Mlangeni’s streetsweeper, who meets us both as someone ordinary (an everyday, or in her case ‘everynight’, worker) and as one who resists any attempt to fathom her fully. In her underdetermined appearance, this ‘invisible woman’ can be read as a visual analogue of Lady Wisdom: immanent to our world of experience, and yet transcending our capacities to get her measure. Wisdom can be an embodiment of God’s presence in the realm of the corporeal but also a gift of the Spirit. Wisdom can assume many guises, and, like Mlangeni’s woman, evoke many associations—she is both the ‘fear of the Lord’ (v.10) and a mixer of wine (v.5); she builds pillared houses (v.1); she transforms vision (v.6).

What is certain is that hers is a feast in which all who long to live according to her ways are invited to share.

Not so Lady Folly. Folly’s feast is not offered in the service of flourishing. She is draped in highly sexualized imagery (v.13) and speaks the language of distorted wants. She offers the false and short-lived satiation of desire depicted in Siopsis’s Melancholia. The statues in Melancholia are commodified bodies. Ironically, what happens when we objectify the other (or others) in this way is that we end up losing our selves.

Mwangi Hutter suggests, by contrast, that where there is no withholding of our presence to one another, there can be a different sort of feast: one in which our desires are both consummated and transfigured. Turquoise Realm offers a vision of how communion in the flesh brings to fruition a blessing that abides. In the Christian tradition to which their momentary Piéta belongs, such communion is the gift of that body which is given and received in the Eucharist: the body of Jesus, who is ‘host’ of this feast. He also bears the name ‘Wisdom’ (1 Corinthians 1:24, 30).

References

Fry, Roger. 1923. Vision and Design (New York: Brentano’s)

Sinnott, Alice M. 2005. The Personification of Wisdom (Ashgate: Aldershot)

Commentaries by Rozelle Robson Bosch