2 Timothy 2

God’s Firm Foundation

Aleksandr Deyneka

Member of a Collective Farm, become an athlete! Колхозник, будь физкультурником, 1930, Poster, 737 x 1040 mm, Russian State Library, Moscow; © Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / UPRAVIS, Moscow

Soldiers, Athletes, and Farmers for Christ

Commentary by Deborah Lewer

The soldier’s aim is to please the enlisting officer. (2 Timothy 2:4 NRSV)

The second letter to Timothy uses vivid metaphors to detail the qualities its recipients should seek to develop in order to serve, to endure persecution, and, ultimately, to share in the ‘reign’ of Christ (2:12). Its writer, traditionally understood to be Paul, encourages these followers of the way of Jesus by pointing to the exemplars of the ‘good soldier’ (2:3), the competitive athlete (v.5), and the diligent farmer (v.6). Timothy and others are to meditate on these models so that they may grow in the understanding given by God (v.7).

‘Collective farmer, become an athlete!’ This is the exhortation emitting in bold red type, underscored with a sharp bayonet, from the vigorous bodies of the disciplined young Russians in Aleksandr Deyneka’s poster. Produced in 1931 in Soviet Russia, its purpose was to drive the campaign to modernize and collectivize farming in the Soviet Union as part of Joseph Stalin’s sweeping and uncompromising ‘Five Year Plan’. But some striking parallels with the rhetorical techniques that the second letter to Timothy uses for its own exhortations are noticeable. Idealized types amplify the message in both cases.

Deyneka’s design is dominated by three athletes, two female and one male, their bodies active and in unison. On the horizon a farmer drives a tractor pulling a plough. Connecting them, in the middle ground, is a muscular worker towelling the sweat from his labouring body. As the agricultural worker with the strength and discipline of an athlete, he embodies the poster’s call. The bayonet suggests both a martial presence and the soldierly discipline that the collective work of state-building in Stalin’s Russia requires. The invigorating wind of organized socialism—so it is implied—drives these model citizens.

Considering the poster together with the passage from 2 Timothy highlights how the classical heritage of the athletic body was mobilized both in Socialist Realism and in early Christian texts as an ideal that was connected with soldierly qualities. The sources for military imagery and images based on athletic competition in the New Testament text are traceable to Greek philosophical contexts (Dibelius and Conzelmann 1972: 33), while Deyneka’s proletarian bodies are related to both neoclassicism and an increasing shift in emphasis to the machine (Groys 2014). In both cases, they are exhortations to ‘be strong’ (2:1).

References

Dibelius, Martin and Hans Conzelmann. 1972. The Pastoral Epistles, trans. by Philip Buttolph and Adela Yarbro (Philadelphia: Fortress)

Groys, Boris. 2014. ‘Alexander Deyneka: The Eternal Return of the Athletic Body’, in Alexander Deyneka (Moscow: Ad Marginem), pp. 45–63

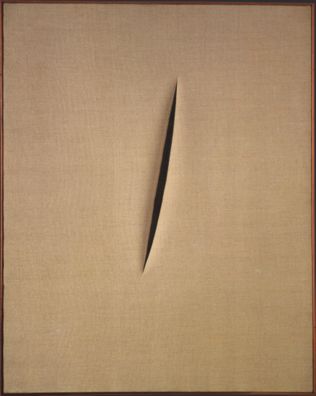

Lucio Fontana

Spatial Concept ‘Waiting’, 1960, Canvas, 93 x 73 cm, Tate; Purchased 1964, T00694, © Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / SIAE, Rome Photo: © Tate, London / Art Resource, NY

The Incisive Word

Commentary by Deborah Lewer

Rightly explaining the word of truth. (2 Timothy 2:15)

The second letter to Timothy is profoundly concerned with the importance of truth (2:14–26). The ‘workers’ in this new movement are called to present themselves to God, unashamed, and ‘rightly explaining the word of truth’ (2:15). ‘Rightly explaining’ here is a translation of a seldom-used Greek term orthotomounta. It appears nowhere else in the New Testament. A literal translation is ‘to cut straight’ (Towner 2006: 521). The King James Version has it as ‘rightly dividing’ (2:15, KJV).

The letter uses the embodied image of a cutting action to specify the abstract concept of truthful explanation. This kind of physical and conceptual gesture finds an echo in the sustained practice of the influential Italian painter and sculptor of postwar modernity, Lucio Fontana.

Fontana titled most of his works with the conjoined terms ‘spatial concept’ (concetto spaziale) and ‘waiting’, or ‘expectations’ (attese). 1960 was the year that marked the beginning of what would become his regular practice of making large monochrome canvases and cutting into them. It was an approach he continued until his death in 1968. These austere works bear a mark of a kind of irrevocable violence, a wound done to the body of the canvas. There are distant echoes of the tearing of the temple curtain (Matthew 27:51; Mark 15:38; Luke 23:45).

For all this, they have a peculiarly still, clean, and graceful beauty. This work does not derive from an iconoclastic whim. A photograph from 1966, taken by Ugo Mulas, shows Fontana ‘opening the canvas with a cut’ (Storck 1994: 51). The artist intuits that the cut prefigures a beginning, a way through to new possibility beyond the surface. In the last interview he gave before his death in 1968, Fontana said: ‘I did not cut holes [in canvases] to ruin the image. On the contrary: I made holes in order to find something else.’ (Storck 1994). In the case of the letter to Timothy, the cutting is of the ‘word of truth’, the unchained word of God (2:9) for the sake of which Paul and others endure.

References

Storck, Gerhard. 1994. ‘Im weissen Raum’, in Im weissen Raum. Lucio Fontana. Yves Klein (Krefeld: Museen Haus Esters und Haus Lange), pp. 7–57 [56–57]

Towner, Philip H. 2006. The Letters to Timothy and Titus (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans)

James Ensor

Skeletons Fighting over a Pickled Herring (Squelettes se disputant un hareng-saur), 1891, Musées Royaux des Beaux-Arts de Belgique, Brussels; Inv. 11156, PvE / Alamy Stock Photo

Stupid and Senseless Controversies

Commentary by Deborah Lewer

Have nothing to do with stupid and senseless controversies; you know that they breed quarrels. (2 Timothy 2:23 NRSV)

The second letter to Timothy offers rich guidance for living well together (2:14–26). Its writer is particularly concerned to warn against the damaging effects of ‘stupid and senseless controversies’ (v.23).

The extraordinary Belgian painter of the Symbolist era, James Ensor, was more alert than most artists to the limitless and often dark human capacity for such folly. In his memorable little panel, two incongruously animate skeletons are locked in a stubborn, futile, and risible struggle over a dried herring. Their scrawny frames are dressed, absurdly, in military paraphernalia. One sports a busby and stiff-necked jacket, the other a shiny-buttoned red uniform.

Ensor focuses the tightly cropped composition on their heads. Their grimaces, jutting jaws, and clenched teeth suggest the obstinacy of their argument over the unappetizing morsel. The diagonal brushstrokes of the vaguely rendered background are as agitated as the figures. It is left to our imagination to visualize the combat in which their limbs might be involved, or to speculate about what the setting for this macabre bout of squabbling might be.

Ensor had an affinity with anarchist socialism. The bitter quarrel imagined here draws as much from Ensor’s rich repertoire of motifs of death and carnival as it does from the daily struggles of the period—including over fishing rights in the seas off the coast of Ensor’s native Belgium (Clark 2016). The image suggests not ‘good soldiers’, but their very opposite: from the perspective of 2 Timothy 2, their advanced decay has gone far beyond, even, the ‘gangrene’ Paul memorably warns ensues when the impiety of ‘profane chatter’ is uncurbed (vv.16–17).

There is none of the painting’s subversive black humour to be found in the epistle’s earnest calls to truth and upright conduct. (v.18). Ensor knew well, however, the chaos to which discord could lead, and employed his own gripping visual metaphors for envisaging its effects.

Reference

Clark, T. J. 2016. ‘At the Royal Academy: James Ensor’, London Review of Books, 43.23

Aleksandr Deyneka :

Member of a Collective Farm, become an athlete! Колхозник, будь физкультурником, 1930 , Poster

Lucio Fontana :

Spatial Concept ‘Waiting’, 1960 , Canvas

James Ensor :

Skeletons Fighting over a Pickled Herring (Squelettes se disputant un hareng-saur), 1891 , Musées Royaux des Beaux-Arts de Belgique, Brussels

Endurance Training

Comparative commentary by Deborah Lewer

The author of the second letter to Timothy has been traditionally accepted as Paul, though the authenticity of Paul’s authorship of this and the other Pastoral Epistles has also long been questioned, with no consensus reached (Dibelius and Conzelmann 1972: 1–10). 2 Timothy 2 opens in a paternal tone fitting for the guidance that is its main subject. The writer addresses Timothy as ‘my child.’ Full of advice and exhortation, the text is a form of communication for which the literary term is parenesis.

This quality especially characterizes this chapter of the epistle. The emphasis is on the discipline, morality, and endurance that Timothy and those ‘faithful people who will be able to teach others as well’ (2:2) are called to show. The writer builds a memorable image of the ‘good soldier’ whose aim should be to please the ‘enlisting officer’—literally, ‘the one who enlisted him’ (v:4) (Quinn and Wacker 2000: 621). An ideal starts to emerge: of troops of resilient followers, fit, in every sense, for active service.

The Socialist Realist imagery of Aleksandr Deyneka’s poster makes for a thought-provoking comparison with the second letter to Timothy. The poster is one of around fifteen that Deyneka produced between 1930 and 1933, while he was a professor teaching drawing composition and poster art at the Moscow Polygraphic Institute. They all address the themes of socialist construction, physical culture, and other aspirations of the Five Year Plan under Stalin’s increasingly authoritarian rule. While they come from very different contexts, both the poster and the epistle call on their recipients to develop the exemplary personal qualities required in the cause of collective attainment. They include the military ‘virtues’ of discipline, obedience, and subordination. They involve competing according to the ‘rules’ and working for a harvest, literal and metaphorical. Deyneka’s recurrent concern with the athletic body has been seen as a ‘mimesis of industrial work’. Its corporeal immortality has also been read as a substitute, in Stalin’s modernity, for a traditional concept of spiritual immortality (Groys 2014: 49). The analogy may help us to reflect further on the ways in which bodily fortitude and moral rectitude are conceived in early Christianity as pre-requisites for a productive life of discipleship.

All should be ready not only to work together for the harvest, but also to suffer as Paul has. As the model for that afflicted yet faithful worker, Paul’s example reminds his readers that suffering is part of the way that followers of Jesus must walk. The task of Timothy and those he guides is not only to develop fortitude and stamina in the face of trials. They must also ‘pursue righteousness, faith, love and peace’ (2:22). A key to attaining such qualities as the Lord’s servant (v.24) is to avoid the kinds of petty quarrels that can damage and weaken collective resolve. The letter is stern in its condemnation both of ‘profane chatter’ (v.16) and of ‘senseless controversies’ (v.23). The one leads to impiety and a spreading infection of the community, the other even to the snare of the devil (v.26). The writer of the letter is particularly concerned about the perils of discordant ‘wrangling over words’ (v.14) among the faithful. The grim futility of the quarrelsome is uniquely imagined in James Ensor’s gloriously incongruous (and only secondarily moralizing) subject of two skeletons fighting over a pickled herring.

If these two works help to visualize the desirable over the undesirable qualities in the body of the faithful, Lucio Fontana’s art, which repeatedly involves the crisp, sharp cutting of the very surface of the work, may offer a more oblique nuance to the text. It resonates with the epistle’s emphasis on rhetorical precision and correct language, ‘rightly explaining the word of truth’ (2:15), which uses a compound word incorporating the verb ‘to cut’. Fontana’s enigmatic practice of inscribing the word ‘hope’ on the reverse of some of his ‘cuts’ makes possible a note of ambiguity in reading a passage that otherwise seems to gain most of its traction from a series of oppositions and indeed from its cutting, separating clarity. There is, throughout, the hope in the ‘firm foundation’ of God’s ‘truth’ and the possibility of ‘gentle’ correction (2:25) within the community—if the message is heard (over squabbles about herrings or anything else!) and true unity of purpose attained.

References

Dibelius, Martin and Hans Conzelmann. 1972. The Pastoral Epistles, trans. by Philip Buttolph and Adela Yarbro (Philadelphia: Fortress)

Quinn, Jerome D. and William C. Wacker. 2000. The First and Second Letters to Timothy: A New Translation with Notes and Commentary (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans)

Groys, Boris. 2014. ‘Alexander Deyneka: The Eternal Return of the Athletic Body’, in Groys, Alexander Deyneka (Moscow: Ad Marginem), pp. 45–63

Commentaries by Deborah Lewer