Titus 1–3

A Common Faith

Kurt Reuber

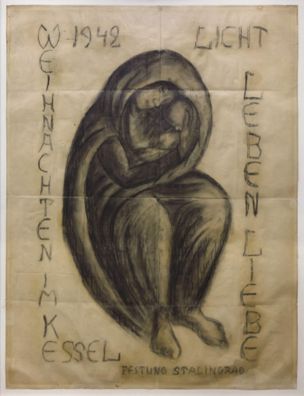

The Stalingrad Madonna, 1942, Charcoal on paper, 900 x 1200 mm, Kaiser-Wilhelm-Gedächtniskirche, Berlin; Azoor Photo / Alamy Stock Photo

Compassion in the Cauldron

Commentary by Ben Quash

[A] bishop [episkopos], as God’s steward, must be blameless;…hospitable, a lover of goodness, master of himself, upright, holy, and self-controlled (Titus 1:7)

The battle of Stalingrad (now Volgograd) was one of the most traumatic crucibles of conflict in the Second World War. Close to 2 million people died. Although it is one of the identifiable points at which the tide of the war turned, the human cost to those caught up in it, on all sides, resists any meaningful calculation.

The maker of this work (now known as the Stalingrad Madonna) was Dr Kurt Reuber. He combined three vocations: those of a trained artist, a Lutheran pastor, and a physician. His pre-war, anti-Nazi views did not prevent his being drafted into the Wehrmacht as a military doctor, and he found himself in a bunker in Stalingrad at Christmas in 1942, enduring the city’s long and devastating winter siege.

‘Amend what [is] defective’, instructs the Letter to Titus, in a summons to reparative living (1:5). The fourth-century bishop John Chrysostom would later acknowledge just how radical the demands of this duty to repair might turn out to be on those whose calling was to teach Christianity (he describes them as ‘physicians of souls’):

But the physician does not strike, but heals and restores him that has stricken him. (Titus 2.7)

Reuber regularly treated the Russian population in Stalingrad as well as his own men, gaining a reputation among the former for his sympathy and compassion, restoring even those who—as, technically, ‘the enemy’—might at any point ‘strike him’.

Four terrible words—along with the date—acknowledge the violence and horror out of which his Madonna and Child emerged: ‘IM KESSEL’, and ‘FESTUNG [fortress] STALINGRAD’:

‘Kessel’ means ‘kettle’ in German as in the modern verb ‘to kettle: to encircle a group of people’. [I]ts older meaning is ‘cauldron’. (Davies 2023: 20)

Yet four other words push back. At top right we read ‘LICHT’ (light), and down the right-hand side, ‘LEBEN’, ‘LIEBE’ (life, love). At left: ‘WEIHNACHTEN’ (‘Christmas’).

Like the Letter to Titus, Reuber—in his pastoring, his medicine, and his art—was seeking wellsprings of repair that were deeper than the ‘unprofitable and futile’ destructiveness (3:9) that surrounded him. Faced with a human violence and sin rarely surpassed in history, he brought something to birth in this artwork that he believed the cauldron would not consume.

References

Davies, Hilary. 2023. ‘Sacramental Landscapes: Coventry Sixty Years On’, The British Art Journal, 24: 15–20

Schaff, Philip (ed.). 1995. Chrysostom: Homilies on Galatians, Ephesians, Philippians, Colossians, Thessalonians, Timothy, Titus, and Philemon, Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers, Series 1, vol. 13 (Peabody: Hendrickson)

Tommaso Laureti

Triumph of Christianity, 1582–85, Fresco, Sala di Costantino, Vatican Palace; Scala / Art Resource, NY

The Fate of the Futile

Commentary by Ben Quash

‘Cretans are always liars’ (Titus 1:12). The Letter to Titus endorses this slur (v.13) but didn’t author it. The early Christian theologian John Chrysostom traces it to a legendary prophet and poet called Epimenides—himself a Cretan—who probably lived in the seventh–sixth centuries BCE. The words are a rare example of a pagan source being quoted in the New Testament.

Chrysostom offers an explanation for Epimenides’s verdict:

[T]he reason he was moved to say it is necessary to mention.…The Cretans have a tomb of Jupiter, with this inscription. ‘Here lieth Zan, whom they call Jove’. (Titus 3.12)

The ancient tradition of a ‘Tomb of Zeus’ on Crete (Jove or Jupiter in his Roman incarnation) is widely attested. It may be a literary invention—though a pre-Hellenic Minoan tomb discovered in 2018 has recently been claimed as the original.

So why did this make liars of the Cretans?

What Epimenides’s lost poem and Chrysostom’s commentary both want to highlight is the naked inconsistency (indeed, the lie) of giving the name ‘god’ to something or someone that can die.

But they differ in their reasoning. Epimenides was unlikely to have had a problem with the idea of Zeus’s (or Jupiter’s) divinity. The lie for him was claiming his mortality. By contrast, for Chrysostom (and, presumably, the Letter to Titus), Zeus’s mortality presented no difficulty at all. Indeed, in a sense Zeus had ‘died’ already. For Christians, the Graeco-Roman deity was a discredited fiction, like the shattered fragments of the idol in Tommaso Laureti’s painted ceiling in the Vatican. The lie was proposing that so unworthy and inconstant an object should ever deserve the dignity of being considered divine.

As in Paul’s sermon on the Areopagus in Athens, related in Acts 17, we have a window here onto the running argument of early Christianity with the religiosity of its Hellenistic environment. The ‘unknown God’ of Acts 17:23 is the only god worthy of the title: immortal, eternal; before all things, and above all things. In such a divinity (to recall the second—and only other—quotation from Epimenides’s lost poem in the New Testament corpus), ‘we live, and move, and have our being’ (Acts 17: 28).

And although, in the humanity he took to himself, this God might be crucified—and even, indeed, buried—no tomb could ever confine such a deity.

References

Schaff, Philip (ed.). 1995. Chrysostom: Homilies on Galatians, Ephesians, Philippians, Colossians, Thessalonians, Timothy, Titus, and Philemon, Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers, Series 1, vol. 13 (Peabody: Hendrickson)

Albert Gleizes

Pour la Contemplation (For Contemplation), 1942, Oil on canvas, 216.5 x 131 cm, Musée de Valence; On indefinite loan from Musée des Beaux-Arts de Lyon, D 2013.2.11, ©️ Musée de Valence; Photo: Éric Caillet

Staying Sound

Commentary by Ben Quash

In 1912, the French painters Albert Gleizes and Jean Metzinger published the first theoretical work on Cubism: Du ‘cubisme’.

In the winter of 1918, while living in New York, Gleizes announced to his wife: ‘A terrible thing has happened to me: I believe I am finding God’ (Robbins 1964: 22).

In 1922, he wrote Painting and its Laws.

Gleizes would not formally be received into the Roman Catholic Church until 1941, but this book was nevertheless an affirmation of faith: faith that the activity of painting was answerable to deep structures and rhythms in reality; faith that—as in this work (For Contemplation)—art could take the parts created by Cubism’s ‘fragmentation’ of our perceptions of objects and ‘interweave’ them into a ‘cadence’ (Gleizes 1999: 36).

‘[R]eality...may be open to discussion’ but ‘is, in itself, nonetheless, sure’ (Gleizes 1999: 47).

Titus is written for a context where unity is at stake and ‘sureness’ highly prized. The pressures towards fragmentation in the infant Christian congregations are repeatedly acknowledged. There are partisan factions to contend with, containing ‘insubordinate…talkers and deceivers’ (1:10). There are ‘myths’ (v.14) and ‘lies’ (v.12) in circulation. The community feels the temptation of ‘various passions and pleasures’ (3:3), and ‘stupid controversies, genealogies, dissensions, and quarrels’ (v.9). All of this threatens the Cretan congregation with disintegration.

It is not surprising, then, that the letter is such a sustained call to integration, even subordinating the liberties of redeemed life (rooted in Christianity’s proclamation of the loving regard of God for women, slaves, and the morally outcast) to an urgently felt need for good order. Emerging authorities in the earliest stages of the Church’s ministry—presbyteroi (‘elders’; 1:5) and episkopoi (‘bishops’ or ‘overseers’; 1:7; 3:2)—are, like heads of caringly-managed households, to maintain the discipline that will prevent the ship of faith from foundering and breaking up.

Thus, the letter is peppered with the words ‘sure’ [pistos; faith-worthy] and ‘sound’ (1:9, 13; 2:1, 2, 8; 3:8).

Gleizes felt a comparably urgent need to address the problem of how to relate the sheer variety of individual experience to some sort of collective order. It left him somewhat isolated as other Cubists turned in new directions. The Dadaists made him a target of ridicule. Yet he persisted in wanting his art to lead ‘towards deeper, more certain, more absolute joys’ than a fragmented, war-wounded world seemed willing to believe possible (Gleizes 1999: 47).

References

Gleizes, Albert and Jean Metzinger. 1912. Du ‘Cubisme’ (Paris: Figuiere)

______. 1999. Art and Religion, Art and Science, Art and Production, trans. by Peter Brooke (London: Francis Boutle)

Robbins, Daniel. 1964. Albert Gleizes 1881–1953: A Retrospective Exhibition (New York: Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation)

Kurt Reuber :

The Stalingrad Madonna, 1942 , Charcoal on paper

Tommaso Laureti :

Triumph of Christianity, 1582–85 , Fresco

Albert Gleizes :

Pour la Contemplation (For Contemplation), 1942 , Oil on canvas

Getting at the Truth

Comparative commentary by Ben Quash

Tommaso Laureti’s painted ceiling in the Vatican and the Letter to Titus have this in common: they can be read either as the works of narrow minds with human-sized ambitions, or as outworkings of a more radical logic whose end is divinely integrative.

At one level, reinforced by its position in the palatial opulence of the Vatican, at the powerful heart of global Christianity, Christ’s cross in Laureti’s painting seems to preside over the humiliating defeat of Christianity’s religious rivals. It is named the ‘triumph’ of Christianity. But at another level, it asks us to ask whether any religion can be wholly secure against the temptation to worship its own idols, the Christian religion included. Whatever the intentions behind this commission—however self-congratulatory of historical Christianity’s worldly preeminence it might be—its content harbours the power to speak a different message.

For, Laureti’s smashed idol represents something other than the loser in a test of strength between rival gods, and that is because the ‘victor’ is himself a loser by just such measures. He is crucified. So, we have to think harder, and ask what a deity would look like who is beyond rivalry; who does not wrestle for ascendancy; whose ‘victory’ is of a different order altogether. Only worship of a god beyond rivalry can give us a way to live that is capable of healing the perennial hatreds of humans; a god who is not on our side at the expense of others. If there is any triumph here, it is not that of a single human movement or institution; it is that of a God whose capacity for limitless giving puts that God beyond the need to compete.

Like Laureti’s painting, the Letter to Titus can invite a somewhat cynical, sociopolitical reading. Isn’t this the predictable assertion of control by certain authoritarian and patriarchal figures over the creative fizz of the charismatic and diverse young congregations on Crete? Maybe. But this letter can also underpin another reading—alongside, even if not instead of, the first.

The Jesus followers under pressure in Crete are seeking what lies deeper than their own party politics, their own doctrinal warfare, their own fragmentation. The epistle encourages them in this search. They are to be repairers (1:5; 3:2); ‘non-futile’ in their common life (3:9); spiritually fruitful (3:8, 14); non-violent in their pursuit and sharing of truth (1:7).

Like any church in any age, the Cretan Christians into whose situation the Letter of Titus gives us a glimpse will have embodied this reality only imperfectly. But the call to ‘amend’ (1:5) that is also embedded in the epistle means that the many imperfections of the many Christian communities who descend from the first New Testament congregations will always—rightly—need to subject themselves to fresh scrutiny. Faith in a God who abides eternally—who is beyond all partisanship—requires ever-new endeavours to overcome lesser allegiances; ever-new attempts at adequacy to ‘the truth which accords with godliness’ (1:1).

Laureti’s dramatic one-point perspective suggests an infinite depth behind the crucified form of Christ. Albert Gleizes, like his fellow Cubists, rejected such one-point perspective. For Gleizes, ‘Cubism was a return to the state of mind that had prevailed prior to the Renaissance’ (Brooke 1999: 25). His visual rhythms echo the patterns of Celtic carved stone.

And yet, despite this, the black rectangles in For Contemplation seem to offer a pathway to our eyes (Art Story n.d.). The path may be tantalisingly untreadable (though in this it is not so different from the fictive corridor in Laureti’s work, which is—after all—on a ceiling: not only a painted fiction, but disappearing upwards). Or it may be treadable only in faith, leading to a depth that is metaphysical not physical. The depth of an abiding truth about reality.

The ‘concentric and peaceable curves’ (Art Story n.d.) of Gleizes’s painting suggest a female form, whose significance can be explicated with the help of Kurt Reuber’s Stalingrad Madonna—made in the very same year as Gleizes’s painting; born in a crucible of violence. As though to deny such violence any claim to ultimacy, it shares with For Contemplation a ‘swirling simplicity, forming a series of ovals that recall the womb’:

It is a perfect image of the serenity, security and care created by a mother’s love for her child. (Davies 2023: 20)

Its gathering power was confirmed by the soldiers who came through a makeshift ‘Christmas door’ to view it: ‘entranced…and too moved to speak in front of the picture on the clay wall’ (Perry 2002: 11).

In the cradled infant, as in the crucified man, we may be confronting the eternal truth revealed by the God ‘who never lies’ (1:2); who gives the lie to all our lies about what a true god is.

References

Brooke, Peter. 1999. ‘Introduction’, in Art and Religion, Art and Science, Art and Production, by Albert Gleizes, trans. by Peter Brooke (London: Francis Boutle)

Davies, Hilary. 2023. ‘Sacramental Landscapes: Coventry Sixty Years On’, The British Art Journal, 24: 15–20

n.d. ‘Albert Gleizes’, www.theartstory.org, available at https://www.theartstory.org/artist/gleizes-albert/.

Perry, Joseph B. 2010. Christmas in Germany: A Cultural History (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press)

______. 2002. ‘The Madonna of Stalingrad: Mastering the (Christmas) Past and West German National Identity after World War II’, Radical History Review, 83: 7–27

Commentaries by Ben Quash