John 9

The Healing of the Blind Man

Thomas Mpira

Jesus the Sing’anga, 21st century, Wood, c. 67 x 40 x 36 cm, KuNgobi Art Craft Center/Mua Malawi; © Thomas Mirpa; Courtesy of Missionsarztliches lnstitut, Wurzburg

Jesus the Sing’anga

Commentary by Martin Ott

Thomas Mpria is a master carver at the KuNgoni Art Craft Centre in Mua, Malawi. KuNgoni is one of the most outstanding art centres in Africa. In works that have Christian subject matter, its artists consistently seek and find successful syntheses between Christian faith and African culture, advancing an African theology in images.

In this carving by Mpira we discover Jesus dressed in the garments of a Sing’anga—a traditional healer in Malawi. He welcomes three people who approach him and ask for healing. These three Malawians are representative of the large numbers of people suffering with different afflictions in Africa. On Jesus’s right is a patient disabled by polio, and on his left a mentally ill person. In the centre is a blind man.

The New Testament describes three miraculous healings of a blind man: at Jericho (Luke 18:35; Mark 10:46; Matthew 20:34), at Bethsaida (Matthew 9:29; Mark 8:22), and at Siloam (John 9). Mpira’s sculpture is an especially appropriate accompaniment to reflection on the third of these—the healing of the blind man at Siloam—for the idea of holistic healing that is especially prominenet in John’s theology has affinities with an African worldview.

In traditional Malawian villages the Sing'anga is considered to possess the power to heal. He knows the properties and uses of herbs and his empathy enables him to discover the hidden sources of disease. His knowledge of medicine and gift of ‘insight’ makes him a connector to the invisible world of the ancestors and of God.

Portraying Christ in the role of both biblical healer and traditional African healer expresses how deeply the longing for healing and redemption is rooted in the cultural setup of the people of Africa. One of the most central concerns for African theology today is how the Christian churches relate to the deep-rooted desire of Africans for healing and purification (De Rosy 1992). If illness is a sign of the religious alienation of human beings from themselves, from their fellow humans, and ultimately from God, then healing and salvation must be viewed as inseparable.

It is only Christ, the traditional and cosmic healer, who can restore health and peace. For this reason, African theologians like Kofi Appiah-Kubi, Cece Kolie, and Bénézet Bujo call Christ ‘the African Healer’.

References

Appiah-Kubi, Kofi. 1981. Man Cures, God Heals: Religion and Medical Practice among the Akans of Ghana (Totowa: Allanheld, Osmun)

Bujo, Bénézet. 1992. African Theology in Its Social Context (Maryknoll: Orbis Books)

De Rosy, Eric. 1992. L’Afrique des Guérisons (Paris: Editions Karthala)

Kolie, Cece. 1991. ‘Jesus as Healer?’, in Faces of Jesus in Africa, ed. by Robert J. Schreiter (Maryknoll: Orbis Books).

KuNgoni Art Craft Centre, available at

Ott, Martin. 2001. Jesus and the Witchdoctor/Jesus und der Wunderheiler. Holzskulpturen des KuNgoni Art Craft Centre Mua, Malawi (Würzburg: Missionsärztliches Institut)

———. 2000. African Theology in Images, Kachere Monograph 12 (Blantyre: CLAIM)

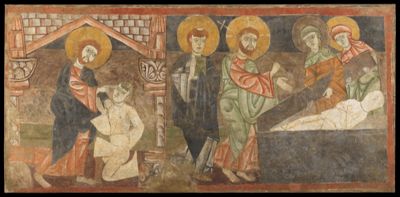

Master of Santa María de Taüll

The Healing of the Blind Man and the Raising of Lazarus, from Ermita de San Baudelio de Berlanga, Caltojar, c.1125, Fresco transferred to canvas, 165.1 x 340.4 cm, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; Gift of The Clowes Fund Incorporated and E.B. Martindale, 1959, 59.196, www.metmuseum.org

Drawing Near

Commentary by Martin Ott

In the Spanish peninsula in the tenth to eleventh centuries, the border between the Muslim Caliphates and the re-captured territories (reconquista) was close to the river Douro in Castile. As the power of the Moors was diminishing, a hermit monk took refuge near Berlanga de Duero where finally a church was built (in 1050) that was later (c.1125) decorated with frescoes that reflect a unique combination of Romanesque and Mozarabic influence.

The paintings were executed by the Catalan Master of Tahull in cooperation with two other painters. Originally they formed a complete cycle depicting the life of Christ above a series of hunting scenes and representations of various exotic animals.

Most of these frescoes have been removed over time, though some remain in situ. Among some that were removed to the USA in 1927 is a fresco representing Jesus healing the blind man.

Jesus is shown with short red hair, a beard, and a halo surrounding his head. He wears an orange tunic and a blue mantle. The blind man is shown kneeling before him. His blindness is symbolized by his closed eyes, which Jesus is touching.

What is striking is the close physical contact between the two men. Jesus not only smears the ointment—made from his spittle—on the eyes of the blind man; he lays his hands on his shoulder. For a blind man these gestures of touch provide the assurance that Jesus is close. Subsequently in the history of the Church the laying on of hands has become a symbol of Christ’s nearness.

It is notable that the adjacent fresco of the Raising of Lazarus also portrays a significant moment of physical contact—and unusually for visual treatments of this scene, Jesus is shown touching Lazarus’s body with his cruciform staff (he more often points towards him).

This portrayal of Jesus’s close physical contact with other human beings conveys a twofold message: it challenges the Romanesque concept of Christ as King and Ruler of the World—a rather distant and remote figure to ‘normal’ people. It also supports the Christian concept of a God who, though invisible, reaches out to the world not only through his word but through acts of physical contact and nearness. A God who is close to those who suffer.

References

Adams, P. R. 1963. ‘Mural Paintings from the Hermitage of San Baudelio de Berlanga, Province of Soria, Spain’, Cincinnati Art Museum Bulletin, 7. 2 : 2–11

Factum Foundation. 2016. San Baudelio De Berlanga: An Architectural Jewel Remade; Exhibition Prospectus (Madrid: Factum Foundation), available at https://www.factum-arte.com/resources/files/fa/exhibitions/dossier/san_…

Frinta, Mojmir S. 1964. ‘The Frescoes from San Baudelio De Berlanga’, Gesta, 1.2: 9–13

Garnelo, J. 1924. ‘Descripción de las pinturas murales que decoran la ermita de San Baudelio en Casillas de Berlanga (Soria)’, Boletín de la Sociedad Española de Excursiones, 32: 96–109

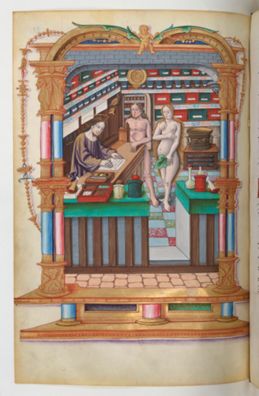

Unknown French artist

Jesus the Apothecary, from the Chants Royaux Sur La Conception Couronne du Puy de Rouen, 1519–28, Manuscript illumination, Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris; BnF, Fr. 1537, fol. 82v, Bibliothèque nationale de France

Christ the Pharmacist

Commentary by Martin Ott

This small illumination develops a very striking theme: Christ is represented as an apothecary in his pharmacy, prescribing the remedy of salvation to Adam and Eve.

In the New Testament, Christ compares himself to a physician (Mark 2:17 and parr.), and from the time of the early Church onwards, theologians continued to interpret him as a healer (e.g. Origen Homily on Leviticus 8; Clement of Alexandria, Paedagogus 1.2) who through his Cross and Resurrection provided the medicine that humanity really needs.

The visual motif of Christ as apothecary which we see here explicitly develops this tradition. It is one of the earliest examples of this iconography in Christian art.

We see Christ working in the dispensary. Adam and Eve present themselves as patients or customers. As their need for a medicine goes beyond their physical ailments, the apothecary Jesus Christ makes out the following prescription which the observer can read when taking a close look: ‘Le Restaurant qui pour mort rend la vie’, that is, ‘The restorative that provides life for the dead’.

The way Jesus cures the blind man in John 9 (‘[he] spat on the ground, made a paste, and put it over the eyes of the blind man’; v.6) has parallels with the apothecary using his medicines. But, as in the manuscript illumination, this is more than a cure for a physical ailment. Jesus not only restores the power of the blind man’s eyes; he also gives him the capacity to see the true light which is himself (John 9:5). The healed man is contrasted with those who assume they can ‘see’ but whose physical sight conceals a spiritual blindness (v.39).

The motif of Christ in an apothecary's dispensary was subsequently adopted widely, especially in France and Germany. (Many such representations offer a valuable historical record of pharmaceutical dispensaries as they existed at the time.)

In modern times, the model of Jesus as healer remains an important but also a divisive one. In European mainline Christianity, the distinction between physical and spiritual healing has led to comprehensive medical services under the patronage of —but distinct from—churches: churches are not pharmacies. In many ‘new’ churches around the globe, however, healing rituals are practised and granted high importance.

In John 9, some of Jesus’s interlocutors are angry and suspicious about his actions. Now as then, the question of how physical and spiritual healing interconnect will draw very diverse reactions.

References

Barkley, Gary Wayne (trans.). 2010. Origin: Homilies on Leviticus, 1–16, The Fathers of the Church: A New Translation, 83 (Washington, DC: Catholic University of America Press)

Krafft, Fritz. 2001. Christus als Apotheker. Ursprung, Aussage und Geschichte eines christlichen Sinnbildes (Marburg: Universitätsbibliothek)

Moles, John. 2011. Jesus The Healer in the Gospels, the Acts of the Apostles, and Early Christianity, HISTOS, 5: 117–82

Porterfield, Amanda. 2005. Healing in the History of Christianity (Oxford: Oxford University Press)

Wood, Simon P. (trans.). 2008. Clement of Alexandria: Christ the Educator, The Fathers of the Church: A New Translation, 23 (Washington, DC: Catholic University of America Press)

Thomas Mpira :

Jesus the Sing’anga, 21st century , Wood

Master of Santa María de Taüll :

The Healing of the Blind Man and the Raising of Lazarus, from Ermita de San Baudelio de Berlanga, Caltojar, c.1125 , Fresco transferred to canvas

Unknown French artist :

Jesus the Apothecary, from the Chants Royaux Sur La Conception Couronne du Puy de Rouen, 1519–28 , Manuscript illumination

Was Blind but Now I See

Comparative commentary by Martin Ott

Jesus devoted himself to the suffering of the sick and disadvantaged in society. Indeed, he had the power to heal in a physical sense. In each of the four Gospels we find several reports of miraculous healings.

John’s Gospel likes to look at the spiritual implications of such healing and embeds miracles and healing into a theological discourse: are miracles a proof that Jesus is the Son of God? What is the link between sin and illness? In John 9, the issue of ‘being blind’ is ultimately embedded in a discourse about faith in the son of God—the light of the world—and the decision to follow him. ‘Jesus said, “For judgment I came into this world, that those who do not see may see, and that those who see may become blind”’ (v.39).

These three artworks from different times and cultures show how Christians have attempted to make this biblical tradition of a healing Messiah meaningful in their respective contexts. They all present Jesus as a person who is physically and emotionally close to sick people, and in two cases this ‘Rabbi of Nazareth’ is depicted helping blind and ailing persons using the medicines and techniques of the artists’ time and place. In one example, Jesus assumes the role of an African Sing’anga (healer) and in another, he takes on the role of an apothecary in Renaissance France. By portraying him as a healer in different settings, Jesus’s power to heal is shown to be truly universal—capable of transforming the reality of people everywhere and throughout history.

John underlines that the ‘man who had been blind from birth’ (John 9:1) is not only blind in a purely physical sense. Rather, he uses ‘blindness’ as an expression for people who are blind to a deeper understanding of reality (vv.35–41). These works of art capture the visible aspect of this encounter between Jesus and sick people. During the healing process Jesus addresses them as individuals and establishes a relationship with them. When Jesus touches and heals, he is fully engaged only with the person before him.

In John’s Gospel he then commands the blind man to go to the pool of Siloam (Shiloh) and to wash the clay from his eyes (v.7). Jesus has led the blind man out of his ‘comfort zone’, that is, away from the confines of his limited worldview and his usual territory. After doing so, the man comes forth seeing (John 9:1–7). For the man who was born blind this is a ‘double-win’: for the first time he is able to see in a physical sense, and at the same time he ‘sees’ the true nature of Jesus. ‘He is a prophet’, says the cured man in John’s Gospel (v.17).

In Christian art, the physicality of the act of healing can be powerfully portrayed. The tactile encounter with Jesus, the face-to-face interaction with the ‘Rabbi of Nazareth’, can be given ‘visual presence’, and this can continue to have great appeal to observers today, especially when they are afflicted or dare to hope for a healing encounter with the Messiah themselves.

It is much more difficult for a ‘visual theology’ to illustrate the spiritual dimension of a healing experience. Examining the details of a healing scene between Jesus and the blind man forces us first to absorb the physical healing; only then the metaphorical meaning of a new vision can be introduced and properly understood. This priority of the physical over the spiritual is, incidentally, a specific feature of visual art against other forms of religious experience. Whether an act of contemplation triggers a spiritual experience will depend on one’s openness to absorb the deeper dimensions of healing, so that one’s inner eyes are also opened and cured of their blindness towards the spiritual reality of life.

Although popular during the first centuries of the Church’s life in the writings of various patristic theologians, the theme of Christ as physician or healer progressively receded into the background of theology and of Christian iconography. Other topics such as Christ the King, Prophet, High Priest, Lamb of God, etc. have achieved more dominance. Until recently, much theology has been oriented towards a separation of body (matter) and soul (spirit) and has seen the principal aim of Christian disciples as being the achievement of eternal salvation in the next life, rather than of wholeness in this one. This has been accompanied by a ‘delegation’ of the area of healing and the physical well-being of the human being to medical practitioners.

The exhibits shown here remind us that in a Christian concept of healing these realities cannot be separated, just as they were not separated in the healing ministry of Jesus.

References

Brown, Raymond E. 2003. An Introduction to the Gospel of John, ed. by Francis J. Maloney (New York: Doubleday)

Moles, John. 2011. ‘Jesus The Healer in the Gospels, the Acts of the Apostles, and Early Christianity’, HISTOS, 5: 117–82

Pilch, John J. 2000. Healing in the New Testament: Insights from Medical and Mediterranean Anthropology (Minneapolis: Augsburg Fortress)

Commentaries by Martin Ott