Acts of the Apostles 28:1–10

Paul in Malta

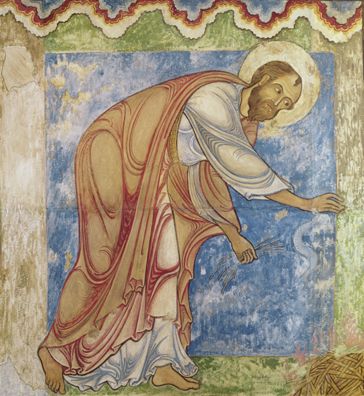

Unknown English artist

St Paul and the Viper, c.1180, Mural, St Anselm's Chapel, Canterbury Cathedral, Kent; Bridgeman Images

The Calm Without the Storm

Commentary by Kristina Zammit Endrich

St Paul and the Viper, together with a few remnants of paint on the adjacent capital and window jamb, are all that remains of a painted decorative scheme that is likely to have covered the entirety of the chapel originally dedicated to Saints Peter and Paul in Canterbury Cathedral.

Here, the drama of the Acts sequence is condensed into its core iconographical elements: saint, serpent, and fire. Gone are any signs of the shipwreck. No Roman soldiers stand beside huddled groups of sailors and prisoners. No kindly islanders carry sticks to feed the fire. The artist has divorced Paul from the geographical and narrative contexts of his twofold deliverance from death. He is stark against a bright blue background, feet bare upon a strip of green earth, as he bends towards the flames.

Paul’s monumental frame fills the composition and commands the viewer’s attention. If he stood upright, he would break through the painting-field, well past the scalloped border of golden clouds along the upper edge of the image—a reminder of his equally monumental importance to the Christian faith. We are effectively drawn into Acts 28:3, the moment the viper is driven out by the heat of the fire and fastens itself on Paul’s hand. And yet, Paul is shown to be unperturbed by the attack.

Despite not having a crowd of shocked onlookers to provide a foil for Paul’s calm demeanour, the effect of his composure is still palpable. The leaping snake only serves to emphasize the natural tranquillity the artist achieves in the masterfully-rendered corporeality of the saint. Paul is flesh-and-blood, but he maintains his faith that God will deliver him as he has done previously, and that he will indeed stand trial before Caesar in Rome (Acts 27:21–26).

Although not at the centre of the composition (see the Benjamin West and Willie Apap versions elsewhere in this exhibition), the fire serves as more than simply the catalyst for the viper’s strike and the site of its demise. Paul’s nimbus would have originally been gilded, appearing so much brighter, as though reflecting the light of the fire he leans over—drawing the viewer deeper into contemplation of the saint’s expression and the blessed assurance revealed there.

References

Nilgen, Ursula. 1980. ‘Thomas Becket as a Patron of the Arts’, Art History, 3.4: 357–66

Willie Apap

The Shipwreck of St Paul, 1960, Oil on canvas, Apostolic Nuntiature, Tal-Virtu', Rabat, Malta; © Estate of Willie Apap; Photo: © Governatorato SVC - Direzione dei Musei (All further use and reproduction strictly prohibited)

Malta’s Paul

Commentary by Kristina Zammit Endrich

As a Maltese artist, Willie Apap would have been intimately familiar with imagery of Acts 27 and 28. Centuries’ worth of Maltese literature, art, and cultural tradition have been devoted to celebrating Paul’s arrival on the islands, and the widespread conversion of faith that followed. In the words of former Superintendent of Cultural Heritage Anthony Pace, ‘images of Paul are, for Malta, as powerful as our national colours’ (Azzopardi & Pace 2010: 5).

Apap’s contribution to the history of Pauline art was painted in 1960 for the nineteenth centenary of St Paul’s shipwreck. The island’s celebration of this anniversary, and the artist’s desire to honour it, speak volumes about the biblical event’s status as cultural landmark for the people of Malta. Decades later, it was chosen as a gift to be presented to Pope John Paul II during his first pastoral visit to the island in May 1990.

Despite the number of figures in the painting, and the fact that a kneeling man occupies the true centre of the composition, Paul nevertheless dominates. With a palette verging on the monochromatic, Paul’s resolute stance and white robes—which seem to glow in the light of the fire—mark him as the main protagonist of Apap’s narrative. The blaze at Paul’s feet is matched by the suffusion of the sky behind his head with light. The natural halo would have been a clear signal to the Maltese viewer: this is your patron saint.

Although the pictorial tension weakens slightly in the far left of the image, where the darkened soldiers seem inattentive, an inward-moving force unifies the composition and brings the central action into focus. The snake isn’t depicted mid-strike, or dangling from the apostle’s hand; instead, Paul is captured in the act of flinging the viper into the fire, the impact of the purposeful motion intensified by the movement of his robes. Apap’s figures appear reminiscent of the work of El Greco (Fiorentino & Grasso 1993: 27–29), their elongated bodies almost a visual parallel to the falling form of the serpent which causes them such physical alarm.

By choosing to paint this mid-air moment, Apap invites the viewer to move past a general familiarity with the theme, and to contemplate instead the precise moment at which the action took place—the moment that heralded the radical transformation of the artist’s (and the original viewers’) own culture.

References

Azzopardi, John, and Anthony Pace. 2010. ‘St Paul in Malta and the Shaping of a Nation’s Identity: Introduction’, St Paul in Malta and the Shaping of a Nation’s Identity (Malta: Midsea Books), pp. 1–20

Fiorentino, Emmanuel, and Louis A. Grasso. 1993. Willie Apap (Malta: Carmelo Zammit la Rosa)

Pace, Anthony. 2010. ‘Acts 27 and 28 in the Shaping of a Nation’s Identity: A Convergence of Literary Form, Art, Architecture, and Landscape’, St Paul in Malta and the Shaping of a Nation’s Identity (Malta: Midsea Books), pp. 35–55

Schembri-Bonaci, Giuseppe. 2009. Apap, Cremona and St Paul: An Essay on the Pauline Iconography of Willie Apap and Emvin Cremona (Malta: Horizons)

Benjamin West

St Paul Saved From a Shipwreck off Malta, 1789, Oil on canvas, Approx. 7.6 x 4.3 m, Old Royal Naval College Chapel, Greenwich, London; Photo: © James Brittain / Bridgeman Images

A Fire of Some Consequence

Commentary by Kristina Zammit Endrich

This monumental altarpiece is the only one of Benjamin West’s major oil paintings to remain in situ. Flanked by double Corinthian columns, and set within a tall arched space, the painting is an imposing focal point for the chapel in which it is set, further emphasized by its palette of warm, rich colours which offset the restrained white, grey, and gold tones of the Chapel’s interior.

Some fifty figures fill the composition, caught in a flurry of activity. Close to the chapel congregants’ direct line of sight, the wrecked ship is visible through a gap in the towering rocky outcrop. The men still trudging through the water to the safety of the shore merge with those in the foreground. Carrying salvaged supplies from the ship, their movement propels the viewer’s eye upwards through a forceful diagonal to the crux of the incident.

The heavenly streams of light that often communicate God’s benediction in religious art are here replaced by the glow of the islanders’ fire which emanates from the very centre of the composition. But even in this new form, light retains its divine significance: the fire illuminates the faces of the survivors, uniting soldier, sailor, and prisoner, by God’s grace unharmed in the raging tempest.

This same light bathes the figures of the Maltese onlookers, the dark bulk of West’s rocky setting intensifying the effect. This theatrical chiaroscuro becomes a poignant reflection of the dramatic spiritual illumination that will shape the identity of a nation. Two men—each with an arm thrown back in fright or wonder at the sight before them—mirror one another at the feet of the man who is the fulcrum-figure in Malta’s history: St Paul. The apostle stands above the fire, right arm outstretched over the flames as a viper hangs from his hand. As the storm rages around them, Paul unknowingly takes his first steps as the future patron saint of Malta (Acts 28:5–6).

The dark serpent is thrown into sharp relief against the Roman centurion’s oval shield, yet the light of the fire betrays no trace of fear on the apostle’s face. West’s Paul is calm and assured, as confident in his God as he is in the heat of the flames as they prepare to devour the snake.

References

Serracino-Inglott, Peter. 2010. ‘“You are All Embarked”: A Short Meditation on Acts 28:1–11 in the Wake of Sundry Philosophers’, St Paul in Malta and the Shaping of a Nation’s Identity (Malta: Midsea Books), pp. 57–65

Unknown English artist :

St Paul and the Viper, c.1180 , Mural

Willie Apap :

The Shipwreck of St Paul, 1960 , Oil on canvas

Benjamin West :

St Paul Saved From a Shipwreck off Malta, 1789 , Oil on canvas

Of Contrasts and Context

Comparative commentary by Kristina Zammit Endrich

Paul’s shipwreck on the island of Malta is not among the more famous events of his life; in truth, it is a rare subject in the history of art. So why might it have been chosen for depiction in these three very different locations, across a period of some eight centuries? In each case, their wider context holds the key.

Benjamin West’s large-scale altarpiece dominates the Chapel of Saints Peter and Paul in the Royal Hospital for Seamen in Greenwich, the chapel naval veterans were once expected to attend every day. The subject of the shipwreck would remind the seamen of their own past preservation, while the kindness shown to the castaways by the islanders (Acts 28:2) would elicit gratitude from the veterans for the comfortable retirement—the ‘safe haven’—their government afforded them.

Similar sentiments might be felt by Maltese viewers of the scene; the gregale storms associated with the biblical event remain a common enough occurrence in Maltese waters. Indeed, the Maltese context proves itself to be the exception to the rule where the rarity of this iconography is concerned; Paul, the patron saint of Malta, is represented repeatedly throughout the visual tradition of the island. Long before the Maltese Islands adopted red and white as their national colours in the late Middle Ages, imagery associated with Acts 27 and 28 was turned to in order to give iconic representation to Malta and her sister island, Gozo. The subject became so interwoven with the Maltese artistic landscape that the Paul of this episode has been dubbed ‘Malta’s Paul’ (Serracino Inglott 2009: 11–14). Willie Apap’s oil painting forms part of this storied tradition.

It is the wall painting in St Anselm’s Chapel, Canterbury, that poses the most intriguing query. Does a painting still contribute to Maltese identity if the Maltese narrative context has been removed from it? Is Paul still the embodiment of euntes docete, ‘go and teach’ (Matthew 28:19), when artistically disconnected from the people he witnesses to?

If we accept the proposition that the Canterbury painting is not, in fact, the sole surviving scene of a homogenous narrative cycle (Nilgen 1980: 363), the isolation of the subject becomes even more conspicuous. In its condensed format, the image then serves as an entry point, an invitation to meditate upon the whole biblical account from storm to fire. The association of the miracle with the invulnerability of those who dutifully follow Christ (Luke 10:19) would not have been lost on those going about their devotions in the chapel. Nor can Paul’s demonstration of virtue before those who thought him an evildoer (Acts 28:4) be separated from Archbishop Thomas Becket’s own very public experience of salvation from spiritual shipwreck. Although a precise date for the fresco is unknown, it has been argued that it probably coincided with Becket’s radical change of conduct and lifestyle upon being elected Archbishop of Canterbury (Nilgen 1980: 366; Martin 2006: 311).

From shipwreck, to snake bite, to miraculous healing, Acts 28 offers compelling testimony of divinely-powered triumph over certain death. As vulnerability and power, fear and faith, jostle throughout this biblical episode, it is perhaps appropriate that each of these artworks presents strong contrasts.

Clinging to his body as though wet, the expertly-executed folds and hems of Paul’s mantle in the Canterbury fresco cascade over him in energetic curves, while his face is focused and serene.

West contrasts a looming landscape and shadowy voids with glowing light to dramatize a revelatory epiphany, and the faith it awakens.

Apap’s composition is a study in contrasts and balance. He foregoes the individualization of the subsidiary figures filling the horizontal composition; instead of portraying unique characters, Apap renders them a nameless crowd. This psychological softening, paired with a similar suppression of tonal contrasts, serves to heighten the viewer’s awareness of the central action taking place. Paul is in sharp focus, the solidity of the semi-clothed figure to the right providing an impressive counterbalance to the forcefulness of the saint’s movement.

And yet, Paul’s expression doesn’t seem to match the confidence of his stance. Gone is the benign calm of West’s oil painting and the Canterbury Paul. Here his gaze is turbulent, as though his thoughts are fixed on something beyond the understanding of the onlooker. Perhaps towards Rome and Caesar, or further still past the events of the final chapter in the Acts of the Apostles.

References

Martin, Francis (ed.). 2006. Acts, Ancient Christian Commentary on Scripture, NT 5 (Downers Grove: InterVarsity Press), pp. 310–13

Nilgen, Ursula. 1980. ‘Thomas Becket as a Patron of the Arts’, Art History, 3.4: 357–66

Schembri-Bonaci, Giuseppe. 2009. Apap, Cremona, and St Paul: An Essay on the Pauline Iconography of Willie Apap and Emvin Cremona (Malta: Horizons)

Serracino Inglott, Peter. 2009. ‘Malta’s Paul’, Salve Pater Paule: A Collection of Essays and an Exhibition Catalogue of Pauline Art (Malta: Wignacourt Collegiate Museum), pp. 11–14

Sparks, Esther. 1971. ‘“St. Paul Shaking off the Viper”: An Early Romantic Series by Benjamin West’, Art Institute of Chicago Museum Studies, 6: 59–65

Commentaries by Kristina Zammit Endrich