Acts of the Apostles 27

‘A Rough Rude Sea’

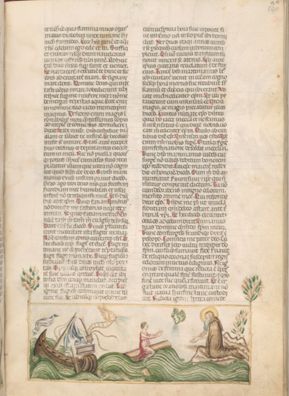

Unknown Italian artist

Martinian of Palestine: Scene, encountering shipwrecked woman, from Vitae patrum, c.1350–75, Illumination on vellum, 356 x 252 mm, The Morgan Library & Museum, New York; MS M.626, fol. 100r, The Morgan Library & Museum, New York

‘Dashed All To Pieces!’

Commentary by Allen Dwight Callahan

This fourteenth-century Latin illuminated manuscript, written in the Italian textura script, was made in Naples, Italy. It is a copy of The Lives of Seventy-two Fathers of the Church and Anchorites, an early medieval collection of saints’ lives. The ink and coloured wash drawing of the manuscript is in the style of the Neapolitan master Roberto d'Oderisio, perhaps by his hand.

The scene is from the life of St Martinian of Palestine. Legend recounts Martinian’s withdrawal to the wilderness, not far from the city of Caesarea, at the age of eighteen. He lived there for twenty-five years as a hermit and ascetic. Later, seeking yet greater solitude and relief from carnal temptations, he became a recluse on an uninhabited island.

Then one day a powerful storm destroys a nearby ship; a woman, clinging to a piece of the wreckage, floats to the island—yet another carnal temptation!

In the scene, framed by two ornamental trees, Martinian encounters the woman. Nimbed, and wearing a cap and monk’s habit, he kneels on the shore at the right of the composition. At left, the ship lists in the sea, its sails torn, its mast broken, its crow’s nest fallen toppling over the stern, as the winged head of a personified wind blows a flailing rope ladder. Beneath the shattered hull of the disabled vessel float the ghostly corpses of several drowned sailors, all stripped naked by the violent waves. At centre, beneath another personified wind, the woman, with both hands raised, is seated on a plank. Her feet dangle in the water.

Martinian’s damsel in distress shows us how some aboard the ill-fated Alexandrian freighter in Acts—perhaps even Paul himself—might have paddleboarded to safety by obeying the centurion's command: ‘jump overboard ... and make for the land ... on planks and ... pieces of the ship’ (Acts 27:43–44).

References

Butler, Alban. 1866. ‘St Martinianus, Hermit at Athens’, in The Lives of the Fathers, Martyrs, and Other Principal Saints, vol. 2: February, 12 vols (Dublin: James Duffy)

Ludolf Backhuysen I

Paul's Shipwreck (Shipwreck of Apostle Paul on Malta), 1690, Oil on canvas, 151 x 204 cm, Ostfriesisches Landesmuseum, Emden; akg-images

‘The Direful Spectacle’

Commentary by Allen Dwight Callahan

Paul’s Shipwreck is by the Dutch painter and calligrapher Ludolf Backhuysen I (1630–1708) who worked primarily in Amsterdam and became famous for his drawings and paintings of seascapes.

Backhuysen’s rendering of the scene is indeed striking. The crippled ship lists at an angle just to the right of centre, buffeted by whitecaps and apparently bereft of crew. The abandoned crow’s nest is pushed askew by the contrary winds, the twisted mainsail beneath it; ‘the forepart’ of the ship here appears to be quite ‘stuck fast’, ‘unmoveable’, and ‘the hinder part ... broken with the violence of the waves’ (Acts 27:41). A menacing sky dominates the entire upper half of the painting and dwarfs the struggling survivors in the foreground.

The painting captures what follows the centurion’s command to those who could swim ‘to throw themselves overboard first and make for the land, and the rest on planks or on pieces of the ship’ (27:43–44). Passengers and crew have already ‘all escaped to land’ (27:44). Backhuysen’s survivors, now ashore, pull rescued cargo to higher ground. Left of centre, one man seems to be hoisting something on his shoulder; at far right, two men drag behind them a large bundle across the beach at the water’s edge.

Yet Backhuysen’s painting is also at odds with the biblical text. The narrative is clear that everything of value—the grain, the ship’s other cargo, even its tackle—had been thrown into the sea by the crew before the ship ran aground (27:18, 19, 38).

Backhuysen’s scene is a salvage operation. But according to the narrative of Acts, there is nothing left to salvage.

References

Broos, B. P. J. 2017. ‘Bakhuizen [Backhuysen; Bakhuisen; Bakhuyzen], Ludolf’, Grove Art Online, Oxford Art Online, available at https://doi.org/10.1093/gao/9781884446054.article.T005827

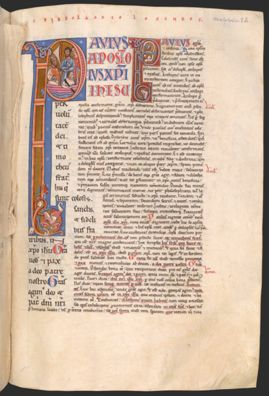

Unknown Spanish artist

The Apostle Paul's Shipwreck, from Pauline Epistles with commentary by Petrus Lombardus, 1181, Illumination on vellum, 365 x 248 mm, The Morgan Library & Museum, New York; MS M.939m, fol. 194r, Courtesy of The Morgan Library & Museum, New York

‘There’s No Harm Done’

Commentary by Allen Dwight Callahan

This illumination from a Latin minuscule manuscript of the Pauline Epistles, with commentary by Petrus Lombardus, was written and illuminated in León, Spain, at the Cistercian monastery of Saints Facundo and Primitivo in Sahagún. According to the colophon, the manuscript was produced in 1181 at the order of the abbot Guterius, who presided over the monastery from 1164 to 1182.

In the illumination, framed in the initial P of Paulus, Paul, faintly nimbed, appears seated in a sailing boat on the water with his hands bound and a rope around his neck. Two men stand at right, one holding the rope that binds him. Between them and Paul stand the ship’s mast and sail. A third man, seated, holds a rudder in his right hand. The Apostle’s name is the first word of the enlarged letters of the phrase, ‘Paul, an apostle of Christ Jesus’, Paul’s typical self-presentation in the openings of his letters.

The illumination suggests the literary synergy of Acts and the Pauline Epistles in the canonical construction of the figure of the Apostle Paul. The Epistles provide only autobiographical snippets about Paul’s life and work: for a narrative representation of the Apostle, commentators have always relied on Acts, where Paul is the principal protagonist for the entire latter half of the book.

The illumination is a scene from Paul’s fateful voyage recounted in Acts 27, which has no explicit referent anywhere in Paul’s letters. Yet though he says nothing of itineraries, fellow travellers, rescues, or recoveries, among his many hardships Paul claims to have suffered not one but three shipwrecks (2 Corinthians 11:25), no doubt setting an ancient record for maritime survival: for most victims of shipwreck in antiquity, their first was also their last.

References

Eleen, Luba. 1982. The Illustrations of the Pauline Epistles in French and English Bibles of the Twelfth and Thirteenth Centuries (Oxford: Clarendon Press), 23 n.129, 77, 85–86, 91–94; 99–101, fig. 168

Unknown Italian artist :

Martinian of Palestine: Scene, encountering shipwrecked woman, from Vitae patrum, c.1350–75 , Illumination on vellum

Ludolf Backhuysen I :

Paul's Shipwreck (Shipwreck of Apostle Paul on Malta), 1690 , Oil on canvas

Unknown Spanish artist :

The Apostle Paul's Shipwreck, from Pauline Epistles with commentary by Petrus Lombardus, 1181 , Illumination on vellum

‘We All Were Sea-Swallowed’

Comparative commentary by Allen Dwight Callahan

Acts 27:1–44 is a very long story—so long that an ancient tradition of biblical manuscripts called the D-text of Codex Bezae has given us a fifth-century ‘Readers Digest’ version of it that is 30% shorter. The prose features the hifalutin vocabulary of the Odyssey: the ship (naus, not the more prosaic ploion) ‘ran aground’ (epokellō); the lifeboat is a skaphos, the Homeric term for a dinghy (27:41). These archaisms, harking back to the storied shipwrecks of ancient Greek literature, along with their obscure nautical terms and detailed geographical references, fill out this colourful, overwritten melodrama.

Paul is the hero, the kibitzer, and the Cassandra of this tale of nautical catastrophe. It is the tale of a voyage troubled from the start. Along the coasts of Asia Minor, Paul and the Roman military police detail in whose custody he had been remanded hitch a ride first on a ship from Adramyttium (up the Aegean coast towards the Troas, v.2), then on a ship laden with wheat from Alexandria, the breadbasket of Rome.

The account opens revisiting the ‘We’ discourse of Acts 16:1, the narrator continuing to speak in the first person plural from Adramyttium all the way to Malta. As the story goes, things looked good at the outset. But only for a minute: the season threatens that the weather must change—for the worse (v.9). Worse than the captain thought: even ‘Fair Havens’, on the southern coast of Crete, turns out not to be so fair (v.12). A freighter would find no shelter among the small bays on its rocky coast.

‘After hoisting it up they took measures to undergird the ship; then, they became afraid that 'they would run on the Syrtis’, (27:17), that is, the notorious sandbanks of Syrtia off the North African coast. The ship lists adrift in the sea of Adria—not the modern Adriatic but the ‘Ionian Sea’, as the Greek novelists called the open sea between Crete, Sicily, Italy, and North Africa. With neither sun by day nor stars at night (v.20), hope fades. So too does appetite (vv.20–21): food is mentioned seven times in six verses (vv.33–38), but on the eve of a shipwreck, neither passengers nor crew have the stomach for it.

Though Paul initially claims that the voyage will be fatal, ‘with danger and much heavy loss, not only of the cargo and the ship, but also of our lives’ (Acts 27:9–10), he later emends his dire prediction, declaring to passengers and crew that ‘none of you will lose a hair from your heads’ (27:34), a prophecy that goes on to be happily fulfilled.

Such is the salvation here: everyone is saved. Yet everything is lost: an entire vessel, reduced to fragments and flotation devices. The motive of the voyage was to transport cargo: the ship is an Alexandrian trading vessel bound for Rome, bearing one of those shipments of Egyptian grain destined to be ground into flour for the bread of ‘bread and circuses’ fame. It is this grain that, after the ship’s other cargo and even its tackle, is thrown into the sea by the crew (27:18, 19, 38). In any shipwreck, valuables have no value, and cargo becomes but unwanted ballast. In this shipwreck, the important question is not how much something costs, but how well it floats.

If the seas always afforded smooth sailing, there would be no need for the salvation dramatized here in the book of Acts. Salvation, after all, presupposes some life-threatening thing from which to be saved. This salvation, however, does not evade catastrophe: it restrains it. Pace Ludolf Backhuysen I’s grand tableau, it is a salvation reserved exclusively for people—not for parcels. And unlike the drowned sailors in the scene from the life of St Martinian, none of those on the Alexandrian freighter are at risk of becoming naked corpses beneath their vessel’s ruined hull. The Apostle Paul, his captors, and the sailor at the rudder pictured in the illumination of the Commentary of Petrus Lombardus, along with their 272 fellow travellers, make it to shore—each and all, safe and sound.

References

Pervo, Richard I. 2009. Acts: A Commentary, Hermeneia (Minneapolis: Fortress Press)

Commentaries by Allen Dwight Callahan