1 Kings 17:1–7; 19:1–14

The Prophet Elijah in the Wilderness

Works of art by Clive Hicks-Jenkins, Dieric Bouts the Elder and Unknown Byzantine artist, Thessalonica

Clive Hicks-Jenkins

The Prophet Fed by a Raven, 2007, Oil on canvas, Collection of the artist; © Clive H. Jenkins; Photo: Courtesy of the artist

Elijah and the Raven

Commentary by Martin O’Kane

The contemporary Welsh artist, Clive Hicks-Jenkins, was much inspired by the episode of Elijah fed by the ravens (1 Kings 17:1–7) and painted two different versions of it. His first encounter with the scene was when he saw it on a Renaissance altarpiece: the ‘Oxford Thebaid’—nine pieces of a fragmented mid-fifteenth-century Tuscan altarpiece held at Christ Church Picture Gallery in Oxford.

He has described how ‘as an unbeliever’, he was ‘smitten with the beauty of the story’. In particular, he was completely taken by the notion of the raven as an emissary of God delivering sustenance to the prophet. As a response to the Renaissance panel, he depicted the scene in contemporary terms.

In this version, Hicks-Jenkins portrays the prophet in modern-day casual dress, drinking tea from an earthenware cup and eating rough bread. He sets the scene against the backdrop of a Welsh hillside while a flaming-red angelic raven not only brings him food but even appears to act, empathetically, as his companion. In his representations of animals in stories with a biblical background, the artist emphasizes that the unusual behaviour of creatures is not simply due to an intervention from on high. Rather, he works from the perspective that the animals are acting from free will which, he argues, is even more compelling and miraculous an idea than having God make them behave against their natures. ‘By such means’ the artist has stated in conversation, ‘I try to find my way into these familiar stories so that I can explore and depict them anew’.

The artist’s distinctive representation of Elijah and the raven adds something new, fresh, and vibrant to the story’s traditional iconography: Hicks-Jenkins, with his keen sense of place, replaces the Wadi Cherith with a green vibrant Welsh hillside, while the dazzling colour of the raven, with wings almost on fire, invites the viewer to reflect on God’s unusual emissary, chosen from the natural world (later it will be an angel, from a supernatural world, who offers Elijah sustenance in 1 Kings 19:5). But, most importantly, the figure of Elijah in contemporary casual garb, evokes the Jewish–Christian interpretation of a prophet who never died and so is very likely to re-appear in any guise, any ethnicity, and in any place or age—here, in sombre mood on an obscure Welsh hillside.

References

O’Kane, Martin. 2018. ‘Painting the Prophet Elijah: The Artistic Appeal’, in The Cultural Reception of the Bible: Explorations in Theology, Literature, and the Arts, ed. by Salvador Ryan and Liam M. Tracey (Dublin: Four Courts Press), pp. 223–24

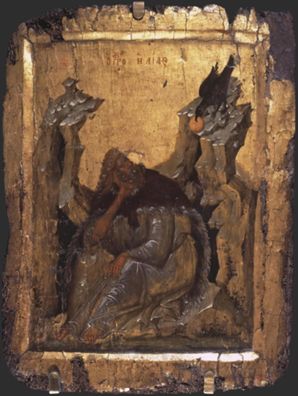

Unknown Byzantine artist, Thessalonica

Prophet Elijah in the Wilderness, Late 14th–15th century, Tempera on panel, 33.5 x 28 cm, The State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg; I-187, akg-images / Album

The Elijah Icon

Commentary by Martin O’Kane

The prophet Elijah is unique in Orthodox Christian tradition in that he is the only Old Testament figure to receive detailed individual treatment on icons. That he was able to gaze on the full glory of Christ during the Transfiguration (Matthew 17:1–8; Mark 9:2–8; Luke 9:28–36) ensured that his partial, yet intense, experience of the divine in the cave at Mount Horeb (1 Kings 19:9–14) would forever hold a central place in Orthodox spirituality.

The prophet must be portrayed according to a strict iconographical canon, summed up by Dionysius of Fourna, author of the eighteenth-century manual on icon painting:

Elijah should be presented as an old man with a white beard. There should be a cave with the prophet sitting inside it; he rests his chin and leans his elbow on his knee. Above the cave, a raven watches him and carries bread in its beak. (1974: 24)

The icon combines two episodes: the ravens bringing food to Elijah as described in 1 Kings 17:6, and Elijah’s mystical experience in the cave, reported in somewhat veiled language in 1 Kings 19:12. The cave encloses the prophet whose mantle touches its darkness on all sides. Orthodox writers stress that the symbolism of the darkness in Elijah icons reflects not so much the personal despair of the prophet as the notion of divine transcendence expressed through Gregory of Nyssa’s theology of darkness, according to which darkness, our essential ‘unknowingness’ of God, represents the culmination of the mystical experience of the divine (Life of Moses, 2:163).

Traditionally, before icon painters began their work, they were required to draw the great eye of God on the unpainted panel and write the word ‘God’ underneath it to remind them that the icon, like a transparent membrane, is not only an image for the viewer to engage with but also a medium through which God beholds the viewer. In this icon, the position of the cave approximates to where the eye of God would have been drawn. Now faded and tattered with age, the icon offers a very moving witness to the esteem given to the prophet by many Orthodox believers through the centuries.

References

Andreopoulos, Andreas. 2005. Metamorphosis: The Transfiguration in Byzantine Theology and Iconography (New York: St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press)

Dionysius of Fourna. 1974. The Painter’s Manual, trans. by Paul Hetherington (London: Sagittarius Press)

Gregory of Nyssa. 1978. Life of Moses, trans. by Abraham J. Malherbe and Everett Ferguson (New York: Paulist Press)

O’Kane, Martin. 2007. ‘The Biblical Elijah and His Visual Afterlives’, in Between the Text and Canvas: The Bible and Art in Dialogue, ed. by J. Cheryl Exum and Ela Nutu (Sheffield: Sheffield Phoenix Press), pp. 61–79

Dieric Bouts the Elder

The Last Supper Altarpiece, 1464–68, Oil on panel, 150 x 180 cm, M Treasury of St. Peter's, M-Museum Leuven; inv. S/58/B, Photo: Erich Lessing/ Art Resource, NY

Heavenly Food

Commentary by Martin O’Kane

The despondent Elijah fortified by the bread and water that the angel brings to him in the wilderness (1 Kings 19:5–8) constitutes one of four Old Testament scenes that anticipate the institution of the Eucharist at the Last Supper in this large multi-panelled altarpiece for the parish church in Leuven.

Two professors of theology, Jan Varenecker and Aegidius Ballawel, were asked to provide the painter with precise instructions as to the choice of subjects: the meeting of Abraham and Melchizedek, the gathering of manna in the desert, the feast of Passover, and Elijah fed by divine providence in the wilderness. The four scenes are thus intended not simply to foretell the Last Supper but also to explain its significance.

In the Elijah panel, the head of the sleeping prophet rests upon his right hand while next to his head are the miraculous sources of sustenance which the angel is about to show him: an earthenware jar of water with bread on top of it (1 Kings 19:6). Dieric Bouts the Elder thus omits the most dramatic moment of the story: Elijah’s awakening and finding this miraculous gift of food. The artist has chosen, rather, to suggest the effects of the heavenly food—for we also see Elijah in the background, nourished both physically and spiritually, boldly setting out on his long and symbolic journey of forty days and forty nights. This will take him to Mount Horeb, the site of his mystical divine experience (1 Kings 19:8). Like the Eucharist, perhaps, this food and drink are a route to theophany.

Bound together by their eucharistic connotations, Bouts also unites the various scenes through the use of a vibrant red—particularly in the outer garments of many of the painting’s figures—and this has the effect of focussing particular attention on the mantle in which Elijah is wrapped, and which also billows confidently in the wind as he makes his journey to Horeb in the background. Shortly afterwards, he will cast this mantle upon his disciple Elisha (1 Kings 19:19) as a sign of passing on his spiritual authority.

References

McNamee, Maurice B. 1998. Vested Angels: Eucharistic Allusions in Early Netherlandish Paintings (Leuven: Peeters)

Clive Hicks-Jenkins :

The Prophet Fed by a Raven, 2007 , Oil on canvas

Unknown Byzantine artist, Thessalonica :

Prophet Elijah in the Wilderness, Late 14th–15th century , Tempera on panel

Dieric Bouts the Elder :

The Last Supper Altarpiece, 1464–68 , Oil on panel

An Enduring and Timeless Prophet

Comparative commentary by Martin O’Kane

Elijah, taken up to heaven in a fiery chariot at the end of his life (2 Kings 2:11), did not experience death and so, in Jewish and Christian tradition, he is eternally alive and present—but his longevity is equally assured by his ubiquitous presence in the rich repertoire of Eastern and Western art.

In Christian iconography, episodes described in 1 Kings 17:1–7 and 1 Kings 19:4–14 frequently merge into one, and are adapted to suit the time and place in which they are painted, as is illustrated by the three paintings selected for this exhibition. The icon and Dieric Bouts the Elder’s painting, perhaps painted in the same century, nevertheless reflect contrasting iconographical approaches to the subject prevalent in the Eastern Orthodox and the Western churches respectively, while the approach of the contemporary artist Clive Hicks-Jenkins shows how Elijah continues to remain a source of inspiration today, to believer and non-believer alike.

All three paintings present a sensitive character study of Elijah at the most decisive period in his prophetic mission when ‘he asked that he might die: “It is enough; now, O LORD, take away my life, for I am no better than my ancestors”’ (1 Kings 19:4 NRSV). The barrenness of the wilderness to which he flees mirrors the sense of rejection he feels within. In each of the three paintings, Elijah is utterly alone, isolated from any form of human companionship; the viewer must engage with a figure clearly dejected, as is implied by the prophet’s posture and body language. In the icon, he rests his chin wearily on his right hand; in Bouts’s painting, he huddles on the ground exhausted, wrapped in his mantle as if for protection. Hicks-Jenkins depicts a figure with slouched shoulders, head slightly bent, perplexed and despairing.

But into this scene of despair, the artists subtly inject a note of hope. In the icon painting, a raven arrives with food, in the shape of eucharistic bread (1 Kings 17:1–7). Bouts depicts an angel touching Elijah reassuringly (1 Kings 19:7) while in Hicks-Jenkins’s version, an exhilarating and dazzling red raven interrupts the sombreness of Elijah’s mood (1 Kings 17:6).

The note of optimism is further enhanced by the artists’ juxtaposition of biblical passages: the icon maker incorporates the episode of Elijah fed by the raven into the scene of his abandonment in the wilderness, and hints at a mystical and reassuring encounter with the divine in the cave in which he seeks refuge. Bouts presents Elijah as a forlorn figure visited by an angel in the foreground of his panel, but, in the background, he paints the prophet confidently striding towards Horeb, as he walks forty days and nights nourished by the food given to him by the angel.

The background and context in which the figure of Elijah appears are significant. For the icon maker, it is the cave, that most sacred space in Orthodox iconography, reserved only for the most important events in Christ’s life, such as his birth at Bethlehem. The context for Bouts is the altarpiece below which the Eucharist is celebrated, thus highlighting the typological significance of Elijah’s bread from heaven in relation to the Last Supper. For Hicks-Jenkins, pre-eminently an artist of place, Elijah appears against a familiar Welsh hillside, green with fertility and hope.

In the larger story of Elijah’s life, there were indeed other events that had perhaps more dramatic appeal, such as the contest with the Baals (1 Kings 19:20–40) or his ascent to heaven in a chariot of fire (2 Kings 2:9–12) and these, too, clearly evoked imaginative and colourful artistic responses. But the three images selected for this exhibition attempt to visualize those biblical passages that describe the prophet’s personal and intimate experiences of the divine, sometimes in coded and ambiguous language—experiences central to the Elijah narrative but that must have proved challenging to the artist. In all three cases—the ravens feeding the prophet in the Wadi Cherith (1 Kings 17:1–5), the angel bringing bread and water in the desert (1 Kings 19:4–9), and the prophet’s intense awareness of the divine presence as he stands at the mouth of the cave (1 Kings 19:11–18)—the biblical author attempts to convey to the reader how the invisible world of the divine impacts on the visible and tangible world of Elijah. In their paintings, the three artists have approached the story from different but complementary perspectives; they reflect not only theological traditions current in their time, but also the potential of these stories to inspire new and personal interpretations today.

References

McMahon, P. 1997. ‘Pater et Dux: Elijah in Medieval Mythology’, in Master of the Sacred Page: Essays and Articles in Honor of Roland E. Murphy on the Occasion of his Eightieth Birthday, ed. by Keith J. Egan and Craig E. Morrison (Washington DC: Carmelite Institute), pp. 283–99

Nocquet, Dany et al. 2018. ‘Elijah’, in Encyclopedia of the Bible and Its Reception (Berlin: De Gruyter), pp. 686–701

Commentaries by Martin O’Kane