2 Kings 2:1–12

Elijah’s Ascent

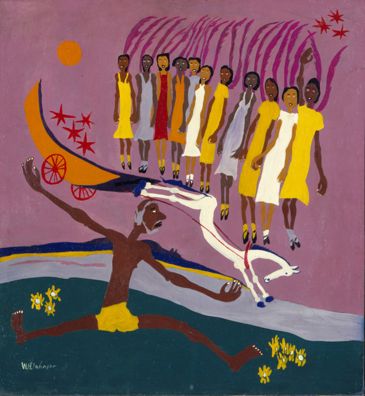

William H. Johnson

Swing Low, Sweet Chariot, c.1944, Oil on paperboard, Smithsonian American Art Museum; Gift of the Harmon Foundation, 1983.95.52, © William H. Johnson / Smithsonian American Art Museum; Photo: Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, DC / Art Resource, NY

Swing Low, Sweet Chariot

Commentary by Victoria Emily Jones

In the African American imagination, Elijah’s ascent has long represented the hope of freedom, of being whisked up and away out of suffering and oppression. One of the most famous African American spirituals is Swing Low, Sweet Chariot, and it was the direct inspiration for William H. Johnson’s painting of the same name.

The refrain goes, ‘Swing low, sweet chariot, / Coming for to carry me home’. And the verses include the words: ‘I looked over Jordan and what did I see? … A band of angels coming after me’; ‘If you get there before I do … tell all my friends I’m coming too’.

Like most spirituals, the language is coded. In one sense, the song is a plea for death, with ‘home’ meaning heaven, the promised land, just ‘over Jordan’. In another sense, ‘home’ could signify an earthly place outside the bounds of slavery, a place of relative safety and liberation and reunion with family—such as the northern US or Canada, over the Ohio River. A clandestine ‘chariot’ was in operation in the early to mid-nineteenth century, run by Harriet Tubman and a network of others (a ‘band of angels’), who transported escaped slaves up to freedom.

In Johnson’s visual translation, a two-wheeled horse-drawn car sweeps down from the upper left, fiery orange and red and filled with stars. Eleven angels in brightly coloured dresses and anklet socks hover above, one of them waving hello to the aged man on the opposite side of the river, who runs to catch his ride. His arms are stretched wide, ready to embrace his new home. Joy awaits him across the river, which the yellow flowers seem to anticipate. God’s presence, the sun’s orb, glows intensely, the same deep orange as the chariot’s exterior. That’s the glory into which the man is heading.

References

Johnson, James Weldon, and J. Rosamond Johnson. 2002 [1925–26]. The Books of American Negro Spirituals, new edn. (Boston: Da Capo)

Powell, Richard J. 1991. Homecoming: The Art and Life of William H. Johnson (New York: Norton)

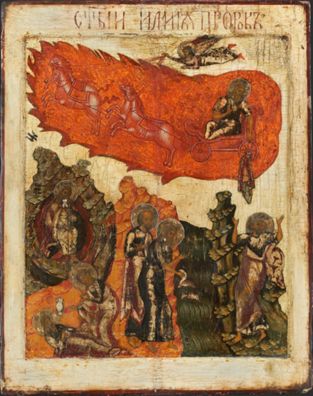

Unknown artist, Russia

The Fiery Ascent of the Prophet Elijah, 1650, Egg tempera on panel, 74.3 x 59.06 cm, Museum of Russian Icons, Clinton, USA; R2010.6, Photo: Courtesy Museum of Russian Icons, Clinton, MA

Elijah the Thunderer

Commentary by Victoria Emily Jones

This seventeenth-century Russian icon shows, in the same pictorial field, four vignettes from the story of Elijah following his flight into the wilderness to escape Queen Jezebel.

Starting from the bottom left, these are:

—an angel laying a cruse of water at Elijah’s head while he sleeps (1 Kings 19:5–6)

—Elijah being fed by ravens as he hides in a cave on Mount Horeb (1 Kings 19:9–14)

—Elijah dividing the Jordan River with his mantle so that he and Elisha can pass over (2 Kings 2:8)

—Elijah being taken up to heaven in a fiery chariot (with an angel at the reins), leaving his mantle to Elisha (2 Kings 2:11–13)

Each episode consists of some supernatural act, emphasizing God’s involvement in the life of his prophet.

The Church Slavonic inscription at the top names the icon: СВЯТЫЙ ИЛИЯ ПРОРОКЪ, ‘Holy Elijah [the] Prophet’. In Slavic countries Elijah— whose feast day is 20 July (a time of year associated with summer storms)—is sometimes referred to as Ilija Gromovnik, ‘Elijah the Thunderer’, as according to local folk beliefs, thunder is caused by the rumbling wheels of Elijah’s skyfaring chariot. In this sense and others, Elijah came to displace the pre-Christian Slavic god Perun, who was associated with thunder, lightning, storms, and fire.

Indeed, the red blaze at the top of this icon is its most striking feature, and it matches the tenor of Elijah’s ministry. He was a fiery prophet, much like John the Baptist who came after him generations later, and to whom he was often compared (Matthew 11:13–14; 17:11–13; Luke 1:17; cf. Sirach 48:1). Yet despite his severity, Elisha is bold enough to ask him for a double portion of his spirit. Elijah tells him that if he sees him being taken away, it will be so, so Elisha raises his hands in an orans position of prayer, expectant (alternatively, this could be read as an expression of astonished exclamation; cf. 2 Kings 2:12)—and sure enough, he witnesses the ascent of his master, who passes him the mantle, with which he will go on to perform twice as many miracles.

References

Cormack, Robin. 2007. Icons (London: British Museum), p. 136

Gilchrist, Cherry. 2009. Russian Magic: Living Folk Traditions of an Enchanted Landscape (Wheaton: Quest Books), pp. 80–84

Kondakov, Nikodim Pavlovich. 2009. Icons (Temporis) (New York: Parkstone Press), p. 122

Tradigo, Alfredo, Stephen Sartarelli (trans.). 2006. Icons and Saints of the Eastern Orthodox Church (Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum), pp. 81–85

Shlomo Katz

Elijah Went Up by a Whirlwind into Heaven (Chariot of Fire), 1985, Oil and gold leaf on plywood, Jewish Chapel of the United States Air Force Academy, Colorado Springs; © heirs of Shlomo Katz; Photo: Victoria Emily Jones

Dancing Toward Glory

Commentary by Victoria Emily Jones

Lining the curved walls of the Jewish Chapel at the United States Air Force Academy in Colorado Springs is a series of nine biblical paintings by Polish Israeli artist Shlomo Katz, commissioned by the Falcon Foundation in 1985. Elijah Went Up by a Whirlwind into Heaven is one of three Katz made on the theme of ‘flight’, a subtle nod to the aerospace branch of military service of the cadets who worship in this sacred space.

The painting should be read clockwise from the bottom right, following the dynamic movement from earthbound thistle patch to open sky and beyond. Elisha, dressed in blue and wearing a kippah, stands with one foot on the ground and the other raised in rapture, his left hand reaching out for his master Elijah’s mantle. Though it would have been a heavier garment that was probably made of sheepskin, Katz renders the mantle as a translucent red swathe of material that spirals around Elijah’s body, accentuating his graceful, balletic form. He is weightless, no longer subject to gravity, it seems, as he twists toward the wispy tongues of flame that form the shape of two galloping horses with a cloaked rider—a celestial cavalry. Flying like a dancer on some grand stage, he who was wrapped in God’s authority now sheds that symbolic wrapping, transferring it to his successor. That the mantle matches the colour of the chariot underscores its divine power.

All this takes place over the desert hills of Israel, with the Jordan flowing through them. In the middle right background is a hill with terraced fields and houses representing Jericho, the last city to which Elijah and Elisha travelled together. The perspective is nonlinear, emphasizing the spiritual dimension of the narrative. Persian, Turkish, and Indian miniature painting as well as Byzantine icons are among Katz’s aesthetic influences.

Katz has captured here that propulsive moment when God’s prophet enters eternity, passing his mantle on to the next generation.

References

Katz, Shlomo. 1993. The Way of an Eagle in the Air: The Paintings of Shlomo Katz at the United States Air Force Academy Cadet Chapel (San Anselmo: Stuart Allen Books)

William H. Johnson :

Swing Low, Sweet Chariot, c.1944 , Oil on paperboard

Unknown artist, Russia :

The Fiery Ascent of the Prophet Elijah, 1650 , Egg tempera on panel

Shlomo Katz :

Elijah Went Up by a Whirlwind into Heaven (Chariot of Fire), 1985 , Oil and gold leaf on plywood

The Fiery Prophet

Comparative commentary by Victoria Emily Jones

The consummate event of Elijah’s life, in which he’s taken up by a whirlwind into heaven, is one of great drama, well suited to visual depiction. The biblical writer describes the exit vehicle as ‘a chariot of fire and horses of fire’ (2 Kings 2:11)—a wild, dreamlike image that can be interpreted in a number of imaginative ways.

Early Christian catacomb paintings and sarcophagi from Rome show a regal Elijah standing at the reins inside a classical quadriga (a chariot drawn by four horses abreast), an iconography indebted to the ancient Greek vases and bas-reliefs that show the sun-god Helios riding his bright chariot from east to west through the sky. No fire element is visible in these Late Antique images of Elijah’s ascent, but fire would become a key feature of paintings of the subject during the late Middle Ages in the West, and of icons in the East.

In his inclusion of a large fiery aureole, our seventeenth-century Russian icon writer follows an iconographic tradition that dates back to the fourteenth century (Cormack 2007: 136), showing Elijah careening through an explosive burst of flame, the red taking up nearly half the composition. The horses blend in, as they appear to be made of fire themselves, and they are driven by an angel who flies overhead, while Elijah stays seated in the carriage.

Painted in his characteristic folk style in 1944—during a time of racial segregation and violence—the vehicle in African American artist William H. Johnson’s Swing Low, Sweet Chariot is more humble: a rough-and-tumble chariot pulled by a single white horse—but with a hint of the mystical in the red stars suspended just above its frame.

Also from the twentieth century, Elijah Went Up by a Whirlwind into Heaven by Polish-born Israeli artist Shlomo Katz has a decidedly Asian flair that is especially pronounced in the ‘chariot’, which is not a chariot at all but, rather, a pair of mythical horse-like creatures seeming almost ready to dissipate. Their appearance is reminiscent of a Chinese dragon (in addition to the acknowledged influence of traditional Persian, Turkish, and Indian painting on his work, the art of China may also have come into play in this painting). Swept up by the rush, Elijah follows the creatures’ trail.

Space is composed differently in these three artworks, taking the eyes along different paths. The icon gives more narrative context for Elijah’s ascent, depicting key episodes from his life story in serial fashion within one frame. The chronological progression meanders in a sort of zigzag pattern, ending at the top left. Johnson’s painting is arranged along a diagonal line that rises from the bottom left to top right. Katz’s guides our eyes in an upward swoosh.

Both Katz’s painting and the icon were made for sacred use but in different religious traditions. The icon is now in a museum, but it would have originally been used by Russian Orthodox Christians in church or in private devotions, for veneration. Katz’s painting was commissioned for, and still hangs in, a Jewish chapel for U.S. Air Force cadets in Colorado; it is one of nine biblical paintings that adorn the walls, helping to connect worshippers to their sacred history and reflecting the beauty of God. Both have—or had—backgrounds of gold leaf. (The icon’s gold has flaked off over time.)

Swing Low, Sweet Chariot is influenced by the black Protestant church tradition, where the African American spiritual from which the painting takes its name is kept alive. The slave song is based on 2 Kings 2, interpreting Elijah’s sky-flight over the Jordan River as a metaphor for death. So the main figure in Johnson’s painting could be Elijah, or he could be a slave or a sharecropper or any man on his deathbed, whom the magenta-winged angels, a choir of black women, beckon across the divide. Conspicuously, there is no Elisha; that’s because the emphasis is on the individual’s homegoing.

Glorious death—or rather, translation into heaven—is one aspect of our select passage; the transmission of power is another. Elijah’s mantle was a sign of his prophetic office, so his handing it over to Elisha signifies Elisha succeeding him in that role. In a larger sense it signifies God giving his people what they need to accomplish his will. On the lateral faces of sarcophagi the scene was often paired with Moses receiving the tablets of the law, and in Biblia pauperum it was related typologically to the ascension of Christ, with the implicit association of the giving of the Holy Spirit to the disciples at Pentecost.

Elijah’s departure, therefore, pictures not only the anticipated future of the saints, who will be gathered up to God, but also the conveyance of authority and mission to be exercised here and now.

References

Cormack, Robin. 2007. Icons (London: British Museum)

Cutler, Anthony. 2005. ‘The Emperor’s Old Clothes: Actual and Virtual Vesting and the Transmission of Power in Byzantium and Islam’, in Byzance et le monde extérieur, ed. by Michel Balard, Élisabeth Malamut, Jean-Michel Spieser, et al. (Paris: Éditions de la Sorbonne), pp. 195–210

Kaltner, John, Richard Bauckham, and David Frankfurter. 2009. ‘Ascension of Elijah’, in Encyclopedia of the Bible and Its Reception, vol. 2, ed. Choon-Leong Seow and Herman Spieckermann (Berlin: De Gruyter)

Lawrence, Marion. 1927. ‘City-Gate Sarcophagi’, The Art Bulletin, 10.1: 1–45

Commentaries by Victoria Emily Jones