Acts of the Apostles 2:1–13

Pentecost

Unknown artist

Pentecost (detail), 11th century, Mosaic, Katholikon of the Monastery of Hosios Lukas, Phokis, Greece; Erich Lessing / Art Resource, NY

Power to Preach

Commentary by Eunice Dauterman Maguire

The Pentecost dome mosaic’s golden surface, in the eleventh-century monastery church of Hosios Loukas in Phokis, crowns the actual liturgical space before the apse, in front of the altar. Peter and Paul face each other at the east, across a gap; behind them the Apostles sit in a circling row, speaking to one another in pairs. The axial division, aligned with the Virgin in the apse holding the divine Child, draws attention to her. This architectural arrangement of the imagery unites the sacramental and human aspects of the salvation that the Pentecost miracle enabled the Apostles to preach (Acts 2:14ff).

Above each Apostle’s halo a ray containing a flame descends from a representation of the Trinity in heaven’s blue disk at the centre of the dome. The dove of the Spirit, facing Mary, perches over the Word, in the form of a golden book, on the throne of the Father. The individual red tongues, like candle flames, hover upright as if sliding down the tapered rays.

Although the Apostles are un-named, and without distinguishing attributes apart from the bound volumes or scrolls representing the Word they would spread, their depictions follow portrait types already established in Byzantium.

Paul’s presence expands the subject here to the authoritative teaching of the faith, beyond a historical event isolated in time; he was not yet a follower of Christ at the time of the Pentecostal gathering described in Acts 3. Yet he would become paired with Peter as an apostolic leader; Paul’s letters to widespread Christian communities explain the need for them to join in proclaiming the faith as God’s word speaking through his people.

There is also a reminder, in the centring of the throne between Peter and Paul, of the orthodoxy established by the Ecumenical Councils. In Byzantine depictions the council delegates sit on either side of the Patriarchal throne in a curved group, just like the Apostles seated at Pentecost.

Unknown artist

Ascension and Pentecost, Late 11th century, Stone relief sculpture, Cloister of the Monastery of Santo Domingo de Silos, Spain; Juergen Kappenberg / Wikipedia

Ups and Downs

Commentary by Eunice Dauterman Maguire

A relief panel in the Spanish monastery cloister of Santo Domingo de Silos: the Pentecost clouds on a stone pier visually connect heaven with earth. A corner column separates the reliefs of the Ascension and Pentecost.

In walking to the cloister from the refectory, the walk at this corner turns east, toward the doors to the library/scriptorium; the chapter house; and the south transept of the church. Passing the Pentecost relief one might notice the attentive Apostles standing with their books and scrolls, Peter holding his keys, and Mary receptive as the Church itself.

In both scenes the figures are in two closely-packed rows as they experience the divine presence under curtains of rippling cloud. The cloud-veil pulled heavenward by angels at the Ascension carries Jesus up, concealing his body, while in the Pentecost scene descending cloud layers part to reveal the earthward-pointing hand of God above the Apostles’ heads, honoured by angels. The sculptural relief, without tongues of fire, borrows the cloud from Revelation (Revelation 1:7; cf. Matthew 24:30; Daniel 7:13) and from the Old Testament’s repeated mentions of the cloud-borne glory of God (e.g. Exodus 24:16; 40:34; 2 Chronicles 5:14; 1 Kings 8:11; Ezekiel 10:4).

The framing arch-shapes of the narrative reliefs articulate in space the monastery’s spiritual embrace of salvation offered through the risen Lord and the Holy Spirit. In each scene, the feet of a participating pair of angels remain invisible in heaven, as medieval Byzantine artists routinely portray them. The angels’ gestures define the moment of God’s Spirit descending. The Apostles receiving it—instead of tilting their heads up, as at the Ascension—appear to be listening to the rushing-wind sound described in the biblical account (Acts 2:2). But the Virgin Mary, standing at the back over a central division between the group’s two halves, looks directly up and raises both hands in acknowledgement.

Her centrality, and the Apostles’ standing pose, also acknowledge traditions from the early centuries of the Church, since the Holy Spirit, coming to her in Christ’s conception, as later to the Church whom she symbolizes, had enabled salvation; and because after Christ’s resurrection and ascension, standing, instead of kneeling, during prayer marked the sanctity of the fifty days between Easter and Pentecost.

Unknown artist

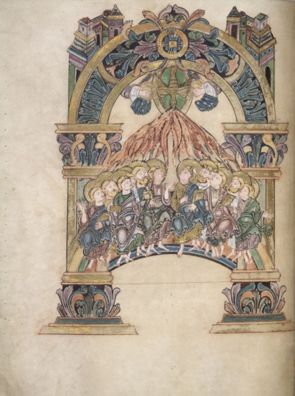

The Pentecost, from the Benedictional of St Aethelwold, 963–84, Illuminated manuscript, 290 x 225 mm, The British Library, London; MS BL Add. 49598, fol. 67v, © The British Library Board

A Canopy of Flames

Commentary by Eunice Dauterman Maguire

The Acts of the Apostles and the book of Revelation combine in this full-page painted depiction of the descent of the Holy Spirit at Pentecost.

Aethelwold, Bishop of Winchester from 963 to 984, is known to have requested, and believed to have personally supervised, the making of the richly illustrated Benedictional, or book of blessings, which includes this image. The Apostles are seated in an ambiguous space, half heavenly vision and half earthly enclosure. As if already attending God in heaven like the twenty-four elders of the Apocalypse (Revelation 4:4), they sit supported by four bands of colour, like a rainbow, in an axially divided group; but their feet rest on a firmer ground line, indicating an apse-like space framed by an arch. A canopy of flames descends toward their heads from the beak of a great diving dove, inside the arch, while angels, dipping downwards with veiled hands, confirm the coming to earth of heavenly power.

A wind-rippled canopy of red and yellow divine light (see Acts 2:2), slightly parted in the middle, shapes the long tongues of fire over the Apostles’ heads (v.3). The pointed tips seem to touch the rims of their golden haloes, while the outermost tongues meet the columns of the framing arch. It is as if Aethelwold and his illuminator (the scribe Godeman, who is believed to have later become abbot of Thorney in Lincolnshire) were hinting at sacred architecture, inspired by illustrations in imported manuscripts, and transposing the motif of parted sanctuary curtains and the actuality of shimmering overhead recesses into the empowering flames.

Aethelwold had previously enshrined his own leadership, as abbot of Abingdon, by giving the monastery a dazzling new church with a curved sanctuary, after bringing it into line with continental Benedictine reforms. As a bishop, he drew his authority from Peter, who holds heaven’s keys in this Pentecost scene, and who alone of all the Apostles in this manuscript wears a monastic tonsure.

Unknown artist :

Pentecost (detail), 11th century , Mosaic

Unknown artist :

Ascension and Pentecost, Late 11th century , Stone relief sculpture

Unknown artist :

The Pentecost, from the Benedictional of St Aethelwold, 963–84 , Illuminated manuscript

Forward-Going Energy

Comparative commentary by Eunice Dauterman Maguire

Space in each of these three depictions, created less than two centuries apart, makes strong but subtle theological arguments across time.

Each was made for a monastic community, in a time of remarkable forward-going energy, encouraged by links to a royal or imperial court. The event of Pentecost, in each, becomes at once topical and universal, by expanding, inflecting or selecting from the biblical narrative. Each gives the story visual expression, not as a simple narrative with a message of unity in diversity, but as a channel in time and in local as well as cosmic space, for multiple and deeply confluent understandings about the divine gift of salvation as delivered by the Church.

The richly embellished page commissioned by Aethelwold (963–84), confirms his purpose of dedication and direction to those who would receive each benediction from the bishop, and go out gifted, like the Apostles from Pentecost. The eleventh-century Hosios Loukas mosaic dome above the living sequences of liturgical movements illustrates their heavenly origin as ceremonies in the Church to which the Apostles had given the divine Word. The stone relief from the cloister of the Silos Monastery offers a spiritual sense of direction to people moving around its cloister and turning a corner from one walk to another.

All of them, by linking heavenly with earthly space, deepen earthly time with heavenly harmonics. They relate the monastic present to the apostolic past, the very beginning of the Church, validating godly lives. In these scenes the Apostles, still very much as earthly agents, become empowered for their special role by the Holy Spirit’s gift to each of them individually. And each of the three depictions connects this dramatic moment to the continuing heavenly mission of those who, by following the apostolic teachings, represent the divine authority that Pentecost bestowed.

The structure of the imagery in each of the three scenes brings heaven penetratingly to earth. On the page, and on the cloister pier relief, as much as in the composition of the scene in the dome mosaic, architectural relationships help to articulate the connection between biblical time and the present. According to many traditions of Christian doctrine, Pentecost is about understanding the divine origins of the Church itself, as endowed with the power and responsibility to bring people to salvation through the word of God. Making the Spirit’s descent visible illustrates the Trinity not just as a doctrinal construct, but as a divine relational reality, capable of responding to human need. Pentecost fulfilled Christ’s promise to his followers: he, as the divine Son (the second person of the Trinity), would ask the Father (the first person of the Trinity), who is Creator of all, to send them a Comforter in the form of the Spirit of Truth (John 14:16–17, 26; 15:26; 16:7–13). This Spirit is identified in theological tradition as the Trinity’s third person: one who would come to earth in ‘another’ form than through Christ’s human incarnation, and would be with them forever.

All three works of art transform the enclosed space in which the event took place— probably the upper room described in Acts 1:13. The Apostles gather in this ‘one place’, sitting, to celebrate Pentecost as the Jewish holiday that took place on the fiftieth day after Passover (Acts 2:1–2). While the Synoptic Gospels recount how Jesus’s last earthly meal (the Last Supper) was a Passover meal in an intimate room, the implicit purpose of the Holy Spirit’s descent is to send out the Apostles from the time and place where they were gathered in Jerusalem.

In roughly the same historical period as the Church was being formed, the Jewish festival of Pentecost became a time for commemorating the giving of the Law to Moses at the burning bush.

It is in the context of that celebration that the Apostles receive divine flames, enabling them to go out and establish Christ’s new law among all peoples: Jews by birth and Jewish proselytes; people from ‘every nation under heaven’ (v.5). Three thousand join their number that day (v.41). As Peter, rising to his feet with the eleven others, explains in Acts 2:38, the gift of the Holy Spirit is offered to all who accept Jesus Christ.

Commentaries by Eunice Dauterman Maguire