John 14:1–17

Finding and Abiding

Brian Whelan

The Last Supper, c.2017, Unknown medium, 91.44 x 121.92 cm, Private Collection; © Brian Whelan www.brianwhelan.co.uk

Finding The Way

Commentary by Alison Milbank

In many representations of the Last Supper Christ is the only agent. Not so in Brian Whelan’s composition. He shows the disciples holding up objects representing their work, such as fish and money bags, or the instruments of their future martyrdom, as they take their part in Jesus’s eucharistic offering.

The Last Supper is not overtly described in John’s Gospel but rather the proto-sacrificial foot-washing. The inner meaning of both supper and washing is, however, being explored in the long Farewell Discourse of John 13–17 in which Jesus prepares his disciples for his going away. In John 14:3, Jesus refers to the many dwellings in his Father’s house and promises ‘I will come again and will take you to myself, that where I am you may be also’.

Clasping their objects, Whelan’s disciples are already predicting and embracing their future heavenly dwelling with Christ, with Judas, in the upper part of the painting, rashly spilling the salt as he reaches for the bread, presaging his own dark participation in suffering. Augustine and Aquinas alike interpreted the ‘many rooms’ of John 14:2 as different levels of beatitude. In a comparable spirit, Whelan reveals an array of character and difference, with John gazing meditatively into the poisoned chalice at the lower left, while Bartholomew at the upper left views the dagger of his future flaying with understandable trepidation, requiring Christ’s comforting words that open the chapter: ‘let not your hearts be troubled’ (John 14:1).

Talk by Christ of his disciples ‘knowing the way’ (John 14:4) prompts Thomas to say that they do not at all know the direction, to which Jesus replies: ‘I am the way, the truth, and the life; no one comes to the Father, but by me’ (14:6). Whelan’s vibrant painting of incipient martyr apostles can be seen as a vivid exegesis of those words. To follow the way of Jesus is to embrace a life of service and of suffering. It will be different for each follower of Jesus, but each personal enactment indwells with Christ and is united to his salvific activity. The way and the dwelling can already be experienced here and now.

Georges Rouault

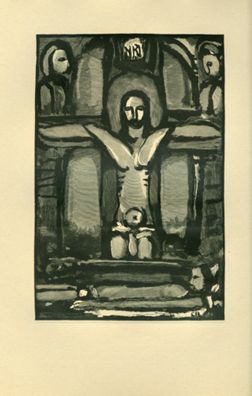

Crucifixion, from 'Passion' (text by André Suarès), 1939, Wood engraving, 438.1 x 336.5 mm, Collection Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo, New York; Room of Contemporary Art Fund, 1939, Edition: 35/245, RCA1939:13.10.18, © Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris Albright-Knox Art Gallery / Art Resource, NY

Showing the Father

Commentary by Alison Milbank

How can you say, ‘Show us the Father’? (John 14:9)

Rarely does Christian art show the Father. I have eschewed the awkward ‘Throne of Grace’ image of the Middle Ages, with the Ancient of Days holding his Son on the cross, which was intended to show the union of the Persons in the atoning death of Christ. I offer you a Crucifixion, nonetheless, since the glory of the Father is revealed in Jesus’s Passion, and Christ’s words in John 14:12, ‘I go to the Father’, imply that Christ offers himself to the point of death.

Georges Rouault’s expressive Christ opens his arms wide and his attention is focused forward. The viewer is brought into direct encounter with this strange figure, in which Jesus is both a strong physical presence in his defined navel and awkward arms, and also an architectural form, his arms shaping the ‘ribs’ of a shadowy arched window. Flanked by gravely attentive, witnessing figures, probably the Blessed Virgin Mary and St John, this Christ does indeed show us our Source as outflowing life and love. The overlay of cross and window means that the light beyond the cross is pressed close to it, recalling an earlier declaration by Jesus: ‘I and the Father are one’ (John 10:30).

Unlike the medieval ‘Throne of Grace’, the Father here does not offer the Son, but the Son is the priestly officiant of his own sacrifice, presiding over his own corpse, which is laid out beneath the cross as the offering. Rouault’s intensely still Jesus is wholly present to our gaze, as he both offers himself and prays for us. The cosmic reach of that prayer is represented by the length of the arms, which extend beyond the edge of the wood engraving. There is a serenity in this Christ, which reaches back beyond the suffering humanity to the divine unchangeableness, and this stability is revealed, paradoxically, in the place of pain. Thus, in the face of Christ, we know and see the Father.

Unknown artist

The Tree of Life (Apse Mosaic of San Clemente), c.1130, Mosaic, Basilica of San Clemente al Laterano, Rome; Scala / Art Resource, NY

Dwelling with the Spirit

Commentary by Alison Milbank

Looking up from the swirling stone pavement, the worshipper in the church of San Clemente in Rome is enfolded in the entangled branches of a giant mosaic vine, inhabited by magpies, farmers, and doctors of the Church. Within the cross, growing as part of this fruitful plant, Christ offers himself among a bevy of white doves, twelve in number to represent the apostles. These are they for whom Christ prayed to the Father that he would send them the Spirit of Truth (John 14:16–17). They have so received that Spirit that they can be shown in His own revealed form of a dove, as at the baptism of Christ.

In John 14:15 the Spirit is ‘another counsellor/advocate’ or ‘Paraclete’, who will abide with them. The description shows the Spirit’s closeness to Jesus, for both Son and Spirit dwell with believers, and both bring them into the communion this mosaic celebrates.

In the mosaic the disciples actually live in the Spirit and within the cross, as nestling birds in the tree of life of the heavenly city of Revelation. Meanwhile, the Father’s victory-garland-like diadem is held over them all. ‘He who believes in me will also do the works that I do’ says Jesus, and even ‘greater works’ because his going ‘to the Father’ (John 14:12) is a journey beyond death to resurrection power, in which his disciples will have a share.

This image unites cross and resurrection as Christ’s priestly action of self-giving becomes the mode of Paradisal life. ‘If you love me, you will keep my commandments’ says Christ in John 14:15, reminding his friends of the new commandment given in the previous chapter, to love one another, as he has loved them. Self-giving of one’s whole being is shown in the mosaic to be generative and productive, weaving every person and creature into an abiding whirl of interconnected life, fed by the blood of Jesus in the true vine.

Brian Whelan :

The Last Supper, c.2017 , Unknown medium

Georges Rouault :

Crucifixion, from 'Passion' (text by André Suarès), 1939 , Wood engraving

Unknown artist :

The Tree of Life (Apse Mosaic of San Clemente), c.1130 , Mosaic

Abiding in the Trinity

Comparative commentary by Alison Milbank

In John 14 Christ provides reassurance for the disciples who are dismayed by his words about going somewhere they cannot immediately follow. He does so by revising their understanding of dwelling-place and abiding, so that the place of connection is the Father himself, the source of Son and Spirit.

You can sense the Father’s presence behind Brian Whelan’s red-robed Christ, who stands with his back to us, with the Spirit the very medium of crimson connection in the space behind the disciples, which is of the very same red. Georges Rouault’s Christ is within the Father’s presence at the heavenly altar, and the Spirit is implied in the burning halo pulsating behind his head. The San Clemente apse mosaic has a more conventional divine hand at the top of the cross, reaching down as if from the heavenly throne to crown Christ with a diadem, but the Trinitarian unity of Persons is nonetheless embodied. Like these images, John 14 is implicitly Trinitarian, impelling us to see the processions of the Son and the Spirit from the Father.

‘Show us the Father’, asks Philip (John 14:8), and the answer is Christ himself. Only through these images of the Son can we understand the nature of his Father. The movement within John 14 is away from seeing a thing or person as a discrete object towards a closer, more intimate mode of knowledge: a union with the object through the indwelling of the Spirit, which encompasses both of us.

These three artworks can only help us understand this way of being if they transform us from viewers to in-dwellers; if we too can find our place in the many mansions of the divine city. We begin at Whelan’s Last Supper, where in the light of Christ offering his body as bread we find our trajectory and role as his disciples, who are also called to follow the way. The truth of the claims of Jesus to be ‘the way, the truth, and the life’ (John 14:6) is confirmed by his self-offering on the cross.

In Rouault’s Crucifixion, we see Jesus’s return to the Father and the cross as the work of the whole Godhead.

The San Clemente apse mosaics represent the holy city of Revelation and the eschatological fullness of life in the ‘many dwellings’ of John 14. Christ has returned and come to take his friends to himself. This life with Christ is one of participation, so St Mary holds her hands in the orans posture of prayer and St John witnesses to the cross as he did in his Gospel. And within and beside the twining vine-branches, people and creatures of all sorts are active in the new heaven and earth.

This wholeness of vision, knowledge, and participation is only partial in the Farewell Discourse, but already the disciples are like Dante after his glimpse of the Trinity in Paradiso 33, whose ‘desire and will were turned | Like a balanced wheel rotated evenly | by the Love that moves the sun and the other stars’. Dante lived out of that experience so that he then moved to a heavenly rhythm. Similarly, the disciples at the last supper are being taught to live out of a deeper mode of connection with Jesus than seeing him physically, to abide proleptically in the ‘many dwellings’ of Paradise.

Commentaries by Alison Milbank