John 13:1–20

Washing the Disciples’ Feet

Works of art by Ford Madox Brown, Workshop of Hugo d'Oignies and Unknown artist, Ancient Egypt

Workshop of Hugo d’Oignies

Foot reliquary of Saint Blaise, c.1260, Oak base covered with silver, gilt, and a rock crystal plaque, 25 x 25 cm; Donated by the Sisters of Notre-Dame de Namur, coll. King Baudouin Foundation, entrusted to the Société archéologique de Namur and on view at the TreM.a – Musée des Arts anciens, Namur, Belgium, Photo: © Guy Focant

The Foot after Christ

Commentary by Michael Banner

Some early reliquaries were simply quite practical means of housing relics being kept for personal use—relatively plain boxes, or small pendants. Later, however, reliquaries were developed for the display of relics to pilgrims or congregations, evoking the meaning of the objects they contained so to elicit devotion (Hahn 2012). In this process, as this reliquary shows, even the lowly foot could become freighted with meaning, and an object of beauty and inspiration.

The finely wrought artwork comprises a wooden core, the upper part of which is covered with sheets of silver. Gilded copper is used for the sole, for the plaque on the top which caps the foot at the ankle, and for the decorated frame of the small rock crystal window through which relics of St Blaise could be viewed. On the plaque, Blaise is depicted standing in the splendour of his episcopal robes, a canopy over his head. But the carved foot itself possesses its own dignity, with its fine modelling, gentle and graceful arch, and elegant toes.

St Blaise was bishop of Sebastea (present day Sivas in central Türkiye) and was martyred around 316 CE. He had reputedly been a physician prior to becoming a bishop, and continued a ministry of healing to humans and animals, right up to his death. Notwithstanding his relative obscurity, he gained considerable popularity in the later Middle Ages as someone whose help could still be sought for bodily ailments (Farmer 2011) and his relics were so prized as to be deemed worthy of costly casing in this and many other instances.

Whether this reliquary contained his whole foot, one or more of its bones, or even some other body part, is unclear. What is clear however (as well as noteworthy) is that a representation of a human foot—base body part that it is—could be conceived as worthy of reverence, rather than of disgust, and a fitting object of prayerful meditation. How does the foot become such an object?

At the close of the foot-washing scene in John, Jesus connects what he has done with the sending out of the apostles—‘he who receives any one whom I send receives me’ (John 13:20). The feet of those whom Jesus sends have been made beautiful. For ‘how beautiful are the feet’—even the feet—‘of those who preach the gospel of peace’ (Isaiah 52:7; Romans 10:15).

References

Farmer, D.H. 2011. The Oxford Dictionary of Saints (Oxford: Oxford University)

Hahn, Cynthia. 2012. Strange Beauty: Issues in the Marking and Meaning of Reliquaries, 400–circa 1204 (Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State University Press)

Ford Madox Brown

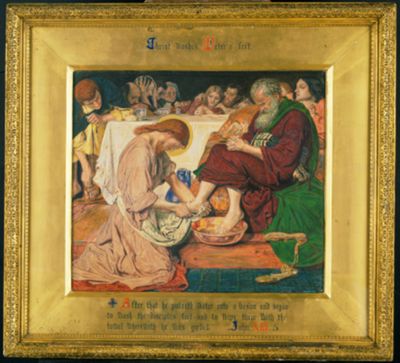

Jesus Washing Peter’s Feet, 1852–56, Oil on canvas, 117 x 133 cm, Tate; N01394, © Tate, London / Art Resource, NY

Intolerable Humility

Commentary by Michael Banner

Peter accepts the washing of his feet, but he does not seem to do so comfortably. His tightly clasped hands, furrowed brow and troubled visage, suggest an uneasy state of mind, even if his initial demurral (‘Lord, do you wash my feet?’; John 13:6) has been overcome. Judas to the left (identified by a bag of coins, being the one who kept ‘the money box’; John 12:6, and his traditional red hair) looks on coolly—but the other disciples seem as unsettled as Peter, and the one with his head in his hands especially so.

What is discomfiting to Peter is presumably just that Jesus should take on a task usually performed by a slave (to use the proper translation). And from the low, close up perspective Ford Madox Brown has chosen, we focus on these two main ‘actors’, but also appreciate that the job of washing a dozen pairs of dusty feet is no mean feat—or rather is a distinctly mean feat. The kneeling Christ, however, bends intently to his task, with the determination which will lead him quite shortly to go out to sacrifice his life. This act of humility and service is both the opening scene and a prefiguration of that later one.

In accordance with ideals championed by some members of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood with which he was associated (albeit not as a member), Brown portrays the scene with a naturalness of action and emotion—and in his first attempt at the work, Christ, who ‘laid aside his garments’ to wash his disciples’ feet (v.4), was depicted in a loin cloth, his legs and torso as bare as they would be at his crucifixion.

But as Peter could barely tolerate that the one he called Lord should so humble himself, no more could Brown’s contemporaries tolerate the depiction of Christ as a naked servant, and so—bowing to public taste—Brown added to the composition the much fuller green robes which Christ now wears. The utter humility of the servant Lord was as intolerable to his later as to his earlier followers.

Unknown artist, Ancient Egypt

Base and feet of a colossus in the name of Amenophis III, c.1391–53 BCE, Granite, 1.57 x 1.44 x 2.25 m, Musée du Louvre, Paris; A 18, Photo: Franck Raux, © RMN-Grand Palais / Art Resource, NY

Feet before Christ

Commentary by Michael Banner

Two vast feet on a pedestal are the remains of what would once have been a monumental statue. This colossus depicted Amenhotep III, who ruled Egypt for nearly 40 years in the early fourteenth century BCE when it was at the height of its power, prestige, and cultural achievement.

The statue would have stood about 8m tall, but for all its monumentality, it was but one small element in Amenhotep’s vast funerary temple at Thebes (Smith 1998: 154–56).

Though merely a fragment, the feet are extraordinarily eloquent of the essence of kingship. To be placed on a pedestal seems to belong to the vocation of rulers, conceived as standing between heaven and earth as guarantors of the good order of their realms. But to guarantee this order, rulers’ feet are essential equipment—they must be ready to put a foot down from time to time, to stamp out any trouble, and even, if it comes to it, to put the boot in.

On the pedestal beneath Amenhotep’s elegant feet, hieroglyphic names of the nations south of Egypt are carved in relief. Around the pedestal’s base are busts of prisoners, hands tied behind their backs. They are linked one to another by the stem of a plant (papyrus) symbolic of Upper Egypt, which winds around their necks.

The statute was made for one of his predecessors, and has simply been reinscribed for Amenhotep. Yet although his standing atop the subjected people of the south does not represent his own direct achievement, but rather an inherited role, it reasserts his readiness to fulfil that role.

Pharaohs are usually depicted without sandals, but used sandals have been found in their tombs, and they surely wore them beyond the confines of palaces and temples. And such is the use to which human feet, especially kingly feet, are put, that even sandaled feet need washing. So too the feet of the disciples. When James and John had requested of Jesus that he ‘grant us to sit, one at your right hand and one at your left, in your glory’ (Mark 10:37), the others were ‘indignant’, not on account of the request, but because James and John got in first. The disciples may have sought thrones not pedestals, but they still needed to learn that sharing in Christ’s Lordship consisted in washing the feet of others, not in putting these others under their own feet.

References

Smith, W.S. 1998. The Art and Architecture of Ancient Egypt, 3rd edn rev. by W.K. Simpson (New Haven. Yale University Press)

Workshop of Hugo d’Oignies :

Foot reliquary of Saint Blaise, c.1260 , Oak base covered with silver, gilt, and a rock crystal plaque

Ford Madox Brown :

Jesus Washing Peter’s Feet, 1852–56 , Oil on canvas

Unknown artist, Ancient Egypt :

Base and feet of a colossus in the name of Amenophis III, c.1391–53 BCE , Granite

His Feet on Earth

Comparative commentary by Michael Banner

The placing of grandiose statues of Pharaohs and other potentates on plinths and pedestals means that the lowly viewer meets the figure not face to face but face to foot. The rituals of monarchy (and of course, of papal monarchy) sometimes demanded the deference of kissing of royal feet with the lips; the positioning of the statues demands the deference of our eyes. The statue of Amenhotep III underlines the demand by placing his subject people beneath his feet—the feet which stand ready to stamp out any trouble from those who would disturb the order over which he presides.

In Ford Madox Brown’s rendering of a scene from John’s account of the Last Supper, the one whom the disciples correctly address as ‘Lord’ (so his nimbus testifies) is nonetheless not raised above the ground, but firmly on it, serving those who are seated on a step above him. Even in his humility, however, as he abases himself by performing the task of a servant with lowered head, there is no humiliation, for Christ is an authoritative and powerful presence.

While the Peter in this painting seems uncertain or troubled at accepting Christ’s ministrations, and the disciples seem variously perplexed, Christ applies himself with solemn assurance and conviction, firmly clasping the front of Peter’s foot with his right hand, and the heel with his left. And the cleansing of the heel surely deserves this attention, for when the foot is used in anger, it is the heel which comes down with particular force—and in fulfilment of the scripture, ‘He who ate my bread has lifted his heel against me’ (Psalm 41:9; John 13:18). Judas, who will shortly slip out into the night, rather sullenly removes or replaces his sandal as he witnesses Christ’s purposeful washing of his disciples’ feet.

Certainly Christ sets an example of humility for his disciples to follow, and so he commands them: ‘you also ought to wash one another’s feet’ (v.14). But his actions also prefigure his death, for as Jesus here ‘lays aside’ his garments, so (in John 10:11, 15, 17 and 18), the Good Shepherd lays aside, or lays down (the very same word), his life. And that greater act of service and humility toward which Christ is now determinedly set, will—like this washing—cleanse those who receive it and even give them a ‘part’ (v.8) in the Lord’s ministry as those whom he has ‘sent’ (v.20).

The foot is a base part of the body—literally so because it connects us to the earth by which is it therefore very likely to be soiled. And just because it is so lowly a part of the body, it can serve as a euphemism, as in the Old Testament, for less mentionable body parts. Thus the seraphim (Isaiah 6:2) are said to use one set of wings to cover their feet (meaning here, as elsewhere, e.g. Exodus 4:25 and Isaiah 7:20, the genitals). But the foot is also base in a different sense, for rulers may have their populations under their heels. Twice over then, the foot needs washing.

But washed, the foot can become an object of great beauty and a source of wonder as Blaise’s reliquary, and countless other finely crafted and bejewelled examples of foot reliquaries, testify. For the foot need no longer be the instrument of oppression, but the harbinger of peace. As Augustine puts it, Christ our head is in heaven, his feet on earth, and his feet are the apostles and all preachers of the gospel ‘for through them the Lord travels among all peoples’ (‘Exposition 2 of Psalm 90’).

Though Ford Madox Brown aspired after a certain historical realism in his painting, he rather casually places some wholly incongruous blue and white china in front of the disciples. His meaning in doing so is by no means clear—but perhaps these modern-day objects serve to suggest a connection between this ‘once upon a time’ washing of a particular set of feet with the here and now, and with the feet of later, and even modern day, apostles.

References

Boulding, M. (Trans.). 2002. Expositions of the Psalms vol. 4: 73–98, The Works of Saint Augustine: A Translation for the 21st Century, part 3, vol.18 (Brooklyn, NY, 2002), p. 340

Commentaries by Michael Banner