Ezekiel 10

Great Wheels of Fire

Works of art by Jost Amman, Melchior Bocksberger, Unknown artist, Northern Italy and Unknown French artist

Jost Amman, after Melchior Bocksberger

Ezekiel's Vision of the Wheel and the Four Living Creatures, 1564, Letterpress, woodcut on paper, 110 x 154 mm, The British Museum, London; 1895,0420.240, © The Trustees of the British Museum / Art Resource, NY

‘Fire from between the Whirling Wheels’

Commentary by Sarah M. Griffin

The Neuwe Biblische Figuren is an early printed German Bible made up almost entirely of pictures. While many of the images are presented with short excerpts of text (four verses in Latin above and their German translation below), these function largely as marginal commentaries (Cramer 2005: 259). This format demands that the pictures tell the story where text is absent, requiring a high degree of detail in each.

To make the prints the artist, Jost Amman, carved the negative space from a woodblock which was then inked and printed onto paper. The resulting work has a linear dynamism, which Amman used to suggest the chaotic energy of the vision. Particularly striking are the finely incised rays of light that emanate from the enthroned God, the outward force of which is continued beyond the clouds in tongues of flame that lick forcefully down towards the earth. The cherubim below are captured in a swirling river of fire (Ezekiel 10:6–7), their wings spread to imply their movement.

The scene’s theatricality is further emphasized by the gestures of the human figures. As the group on the left look at one another in disbelief, Ezekiel, overwhelmed by the glory of God, has dropped to his knees in prayer.

All of this together gives the viewer a sense of the frightening majesty of the vision, which in its first occurrence (in Ezekiel 1) even caused him to ‘fall upon his face’ (v.28).

While the other two works featured in this exhibition focus on a particular part of Ezekiel’s visionary experience, this print represents most of the book of Ezekiel and thus refers to details from other passages. Earlier in the book, God commands that Ezekiel eat his scroll so that he can ‘speak to the house of Israel’ (3:1). Here, Jost Amman shows the scroll flowing from a celestial hand into Ezekiel’s partially opened mouth.

In this world of airy energies, it is as if he is breathing in the words of God.

References

Cramer, Thomas. 2005. ‘From the World of God to the Emblem’, in Visual Culture in the German Middle Ages, ed. by Kathryn Starkey and Horst Wenzel (Springer: New York), pp. 251–71

Unknown artist, Northern Italy

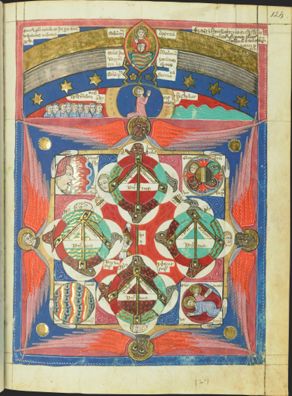

Descriptio Rote secunde iuxta vitulum. Et secunda pars secunde dispositionis, from Henricus de Carreto's 'De Rotis Ezechielis', c.1313–15, Manuscript illumination, Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris; MS Lat. 12018, fol. 124r, Bibliothèque nationale de France: https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b10025464s

The Entirety of Scripture

Commentary by Sarah M. Griffin

The wheels of Ezekiel do not only represent one man’s visionary experience; they signify the entirety of Scripture (perfecta sacre scripture). So wrote Henricus de Carreto in the dedication of his manuscript, the De Rotis Ezechielis (‘On the Wheels of Ezekiel’), of which only two copies exist. This image is found in the original copy of the manuscript: a lengthy theological text illustrated with twenty-five diagrams. These show the wheels in various stages of movement and different degrees of scale, to guide the reader through their multiple layers of symbolism.

This particular image is one of the first in the series and depicts Ezekiel’s visionary experience in astounding detail, bringing the strangeness of the descriptions to life before the readers’ eyes. Taking the description of the wheels as its model, each wheel has the four faces of the four creatures (Ezekiel 10:14) and all have eyes (v.12). Framing the wheels are the cherubim, who have ‘the form of a human hand under their wings’ (v.8).

By following the biblical description exactly, the image maker’s intention was evidently to capture the vision as precisely as possible, with the consequence that both the schematic structures as well as the figures upon them were laden with scriptural meaning.

Described as like wheels within wheels (cf. 10:10), the potential of the wheels to be represented as concentric circles made them a fitting foundation upon which to represent the complex-yet-simple wholeness of the scriptural canon. Through them, Henricus attempted to picture their detailed description whilst explicating their theological and cosmological significance, discussed at length in the patristic texts that were in circulation during the Middle Ages (Dow 1957: 273–79).

Yet the schematism of a diagram, however geometrically constructed, cannot tame the unsettling strangeness of this theophany, whose energy also radiates from the page. As Origen exclaimed: ‘what could be more glorious and exalted than these things?’ (Commentary on The Gospel of John 6.23).

References

Dow, Helen. 1957. ‘The Rose-Window’, Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes, 20.3: 248–97

Unknown French artist

A panel from the Book of Ezekiel Window, c.1246–48, Stained glass, Sainte-Chapelle, Paris; Bridgeman Images

A Cage of Colour and Light

Commentary by Sarah M. Griffin

At the very core of Ezekiel’s visionary experiences, the first described in Ezekiel 1 and the second in Ezekiel 10, is the appearance of the four cherubim and the wheels of God’s chariot throne. These features come to represent Ezekiel’s visions in this stained-glass window panel in the Sainte-Chapelle, Paris.

Built as the royal chapel of the residence for the Kings of France, the Sainte-Chapelle was commissioned by King Louis IX around 1238 to house the precious relics he had recently acquired. A literally brilliant feat of Gothic engineering, the walls of the upper chapel are almost completely given over to vibrant stained glass, creating a cage of colour and light that tells the story of Christian salvation history from Genesis to the Last Judgement.

Near the east end of the chapel, an entire window is dedicated to the book of Ezekiel. The panel is just one of thirty scenes that form a rich and carefully constructed narrative, designed to be meditated upon by the king but also enjoyed by the poorest inhabitants of medieval Paris (Cohen 2015: 148).

Ezekiel stands in the centre of this quatrefoil-shaped panel with a book in his left hand that probably contains his prophecy. He looks upon the four cherubim, who appear here as the winged symbols of the Evangelists: John as an eagle, Mark as a lion, Luke as an ox, and Matthew as an angel. This depiction had become common as Christian tradition read the cherubim via the book of Revelation (4:7). Above and behind him are waves of blue that disappear into the top of the frame, representing the firmament that appears ‘something like a sapphire’ (Ezekiel 10:1).

While the composition of the scene is simple, some details show its medieval makers grappling with the complexity of the description of the wheels, which were ‘as if a wheel were within a wheel’ 1:16; 10:10). Depicted twice in the panel, they are visualized as multicoloured concentric circles on the left and as a vertical line of four overlapping circles above Ezekiel’s raised right hand.

References

Cohen, Meredith. 2015. The Sainte-Chapelle and the Construction of Sacral Monarchy: Royal Architecture in Thirteenth-Century Paris (Cambridge University Press: Cambridge)

‘The Book of Ezekiel, Sainte-Chapelle’, The Medieval Stained Glass Photographic Archive. Available: http://www.therosewindow.com/pilot/StChapelle/w10-scan-Frame.htm [accessed 3 March 2020]

Jost Amman, after Melchior Bocksberger :

Ezekiel's Vision of the Wheel and the Four Living Creatures, 1564 , Letterpress, woodcut on paper

Unknown artist, Northern Italy :

Descriptio Rote secunde iuxta vitulum. Et secunda pars secunde dispositionis, from Henricus de Carreto's 'De Rotis Ezechielis', c.1313–15 , Manuscript illumination

Unknown French artist :

A panel from the Book of Ezekiel Window, c.1246–48 , Stained glass

‘As if a Wheel were within a Wheel’

Comparative commentary by Sarah M. Griffin

The visualization of Ezekiel’s visions of the chariot throne demands a powerful imagination. It is fantastical and bordering upon contradictory in its description of natural phenomena and cherubim, and even more so in its account of the wheels.

Their appearance was ‘as if a wheel were within a wheel’ (Ezekiel 10:10), they moved ‘in any of their four directions without turning as they went’ (v.11), and their rims were ‘full of eyes’ (v.12). The interrelation of the wheels and their movement required visualization beyond two-dimensional representation, challenging their illustrators to experiment with a variety of circular forms.

These three depictions of Ezekiel’s visionary experience, all in different media, demonstrate the diversity of representational strategies used by medieval and early modern artists to capture the appearance of the wheels. Despite their variety, all of them reveal an impetus to visualize a complicated, moving, three-dimensional structure upon a two-dimensional plane.

The stained-glass panel shows two different methods of picturing the wheels: the first as multicoloured concentric circles, and the second in a smaller and less obvious grisaille window fragment, placed above Ezekiel’s extended right hand, as if he is presenting them to the viewer. In this smaller depiction, the wheels form a vertical line of interlinked circles, echoing the columns of roundels that form the whole of the Ezekiel window.

In the manuscript illuminations of the De Rotis, the wheels provide the structural foundation for the diagrams. In this particular image, the four wheels are arranged within a diamond formation. Tied together by golden lines, their interconnectedness is emphasized by their eyes, all of which look toward the wheel they are linked to. The diagram is then repeated three more times on separate pages, though in each case the diamond structure has been rotated ninety degrees, showing the movement of the wheels as described in Ezekiel 10:11 (Stones 2014: 143–50).

In the printed German Bible, the wheels become a three-dimensional structure, not dissimilar to the scientific instruments used at that time. Faced with the same issues as the makers of astronomical diagrams and models that illustrated the structure and movement of the cosmological spheres through circular rings, it is not surprising that this later image looks like an armillary sphere (a model of the universe in which a framework of concentric rings represents the movement of celestial bodies around the earth). Looking closely, it becomes something of an impossible object, entangling the viewer’s gaze within its overlapping rims and spokes.

Placed in chronological order—from stained glass to manuscript diagram to woodcut print—these works show a growing awareness of three-dimensional space: from simplified circles that engage one another in different ways, to repeated schematic structures whose slight variation implies movement, to the use of perspective. Like Ezekiel’s reports of his mystical visions, these visualizations become increasingly complex.

Yet it is not only the complicated descriptions of wheels within wheels that make Ezekiel’s visions so difficult to represent. Their interpretative history in Christian tradition makes them part of a dense typological network that draws different stories from the Old and New Testaments into relationship in order to reveal further and potentially deeper meanings.

All three of the artworks are part of larger visual programmes. The print portrays most of the book of Ezekiel within a collection of images that covers the entire Bible, while the panel of stained glass is a snapshot from the book of Ezekiel, which makes just one window in an entire building of images that tell the story of Christian salvation history.

Meanwhile, the diagrams of the De Rotis focus on the descriptions of the wheels in such detail that they become symbols of the entirety of Christian Scripture. Through the diagrams, Henricus and the illuminators who worked on his text unlock a further theological meaning of the wheels, the typological and cosmological implications of which are explored in patristic commentaries on Ezekiel. According to Jerome, the four wheels were analogous to the Evangelists and to various fours within the natural world—the elements, seasons, and cardinal directions—demonstrating how Scripture informed humankind’s understanding of the world (Dow 1957: 274). In Henricus’s manuscript the wheels are a biblical instrument, used to demonstrate the many layers and interconnectedness of Scripture.

References

Bergeron-Foote, Ariane. 2016. ‘The Wheel of Ezekiel: The Preeminence of the Face of the Lion’, Dr. Jörn Günther Rare Books: 1–9

Christman, Angela. 2005. What did Ezekiel See? (Leiden: Brill)

Dow, Helen. 1957. ‘The Rose-Window’, Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes, 20.3: 248–97

Neuss, Wilhelm. 1912. Das Buch Ezechiel in Theologie und Kunst bis zum Ende des xii. Jahrhunderts, mit besonderer Berücksichtigung der Gemälde in der Kirche zu Schwarzrheindorf (Münster)

Stones, Alison. 2014. Gothic Manuscripts 1260–1320, Part 2, vol. 1 (London: Harvey Miller)

‘The Book of Ezekiel, Sainte Chapelle’, The Medieval Stained Glass Photographic Archive. Available: http://www.therosewindow.com/pilot/StChapelle/w10-scan-Frame.htm [accessed 03 March 2020]

Commentaries by Sarah M. Griffin