Exodus 35–40

The Tabernacle: Evolutions of Intimacy

Unknown artists

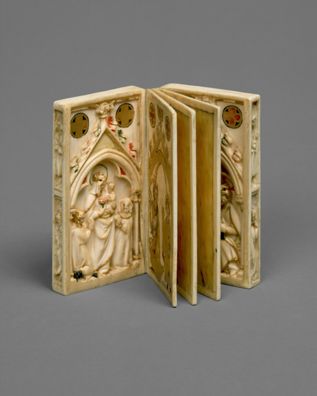

Booklet with Scenes of the Passion, c.1300–20, Elephant ivory, polychromy, and gilding, Overall (opened): 7.2 x 8.1 x 1.2 cm; overall (closed): 7.2 x 4 x 2.2 cm, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; The Jack and Belle Linsky Collection, 1982, 1982.60.399, www.metmuseum.org

Participating in the Story

Commentary by Xiao Situ

This medieval ivory booklet is no larger than the palm of one’s hand, yet it contains an elaborate collection of images, both carved and painted. The exteriors of the covers feature scenes in relief from Christ’s Passion; the interiors of the covers display representations of the Virgin, also in relief; and the first and last pages include paintings of angels and the Magi in Adoration. Even the vertical ends of the covers are carved with narrative figures from the last hours of Christ’s life.

In contrast to these highly decorated parts, the four central pages of the booklet are left blank. This unadorned space was meant for the application of thin layers of wax, on which personal prayers could then be inscribed using a stylus. The interactive nature of these blank pages enabled a bond to form between the devout owner and the religious events depicted on the booklet. The owner not only got to hold the story of Christ’s Passion in their hands, but also became a participant within that story by ritually inserting intercessory prayers.

According to Exodus, the craftspeople who built the tabernacle included carpenters and metalworkers, woodcarvers and weavers, embroiderers and jewellers, perfumers and engravers. With the exception of Bezalel and Oholiab, whom God designated as the project’s supervisors (35:30–36:3), the book of Exodus does not identify any of the artisans by name. And yet God’s detailed instructions for creating and installing the tabernacle’s components are repeated three times, suggesting the importance of their role in the story of God coming to reside among his people.

Just as the owner of the ivory booklet formed a bond with the events of Christ’s Passion by inscribing prayers onto the blank pages, so too the tabernacle’s makers formed emotional and bodily connections to the larger story of God coming to live among Israel. The artisans’ skill and labour counted as prayers. Stitched, gathered, and multilayered like the ivory booklet, the tabernacle symbolizes the enfolding of the makers’ embodied prayers into the larger story of God’s relationship with his people.

Julia Rooney

IMG_0320, 2020, Oil on linen, 5.08 x 5.08 cm, Collection of the artist; © Julia Rooney, Image courtesy of Julia Rooney Studio

The Tabernacle as Image

Commentary by Xiao Situ

By holding one of her original miniature paintings next to its online double, artist Julia Rooney stresses that although the two are related, they are not one and the same.

While the photo-sharing app Instagram faithfully conveys the original painting’s abstract geometric design and two-by-two-inch scale, it does not adequately show the painting’s three-dimensionality: the thick impasto warps the square into an irregular shape, giving it the semblance of a tiny found object.

In her right hand, Rooney tilts the painting slightly forward and to the right, making visible the upper and left edges of the canvas—she seems to want us to grasp the object’s tile-like density. In the app, however, the painting’s depth is somewhat diminished; only a thin shadow on the bottom suggests its bulkiness.

Rooney’s 2021 exhibition @SomeHighTide included one hundred of these miniature abstract paintings, each of which was also digitally reproduced on its Instagram page of the same title. The exhibition coincided with the global COVID pandemic. Tempered by health concerns and safety protocols, individuals who were unable to see the paintings first-hand at the Arts & Leisure Gallery in New York City could access digital reproductions of them on Instagram. The exhibition explored the gains and losses of visual experience when original works of art are photographically reproduced, digitized, and made widely available on social media.

By juxtaposing an original painting with its digital copy in this photograph, Rooney revives a central premise made by John of Damascus in his eighth-century apologia for holy images:

An image is a likeness of the original with a certain difference, for it is not an exact reproduction of the original…. Let us understand that there are different degrees of worship. (John of Damascus, On Holy Images)

The Israelites’ idolatrous worship of the golden calf (Exodus 32:1–20) was still recent history when God gave Moses the tabernacle instructions. By engaging the Israelites in the building of the structure, God was perhaps impressing upon the people through their embodied work and artisanal labour that the tabernacle was a crafted object—not divine in itself, but an ‘image’.

Exodus repeats the tabernacle directions three times, perhaps to emphasize the structure’s material and human-made nature. By involving the Israelites in the construction, God may have been honing their ability to distinguish between what is original and what is image; between the divine and a reflection of it.

References

John of Damascus. 1898. St John Damascene on Holy Images, trans. by Mary H. Allies (London: Thomas Baker), pp. 10, 13

Mary Roberts

Hester Middleton, c.1752–58, Watercolour on ivory, 3.8 x 2.5 cm, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; Purchase, Dale T. Johnson Fund and Jan and Warren Adelson Gift, 2007, 2007.64, www.metmuseum.org

The Intimacy of Distance

Commentary by Xiao Situ

This portrait miniature of Hester Middleton is one of five that artist Mary Roberts painted of a group of cousins—the children of brothers William and Henry Middleton—in the mid-eighteenth century. The brothers and their children were separated by transatlantic distance: William lived in Charleston, South Carolina, while Henry resided in Suffolk, England.

The commission of this set of portraits symbolizes the Middleton family’s affirmation of the strength and intimacy of their kinship across a vast ocean. By virtue of their diminutive size and delicate artistry, the portraits ask to be cradled in one’s palm, held close to the beholder’s eyes. Through the intensity of their gaze and the feelings of affection these objects inspired, the beholder and the beheld might momentarily transcend the barrier of distance.

The installation of the tabernacle in their midst can also be interpreted as the Israelites’ affirmation of intimacy through simultaneous closeness and distance. The materials offered for building and furnishing the tabernacle were the people’s most cherished possessions: gold jewellery, silver and bronze tableware, linens and animal skins, stones and gems, oils and spices. By offering their prized belongings for the communal construction of the tabernacle, the Israelites traded in their closeness to personal objects for closeness to God.

Likewise, the craftspeople who made the tabernacle’s furnishings spent a great deal of time forming visual and tactile bonds with the materials they handled. Imagine the fingers of the weavers and embroiderers as they worked the linen, coloured yarns, and goats’ hair into curtains and coverings; the jewellers and engravers knitting their brows in concentration as they cut and set the stones for the priestly garments; the arms of the carpenters and metalworkers swinging arcs in the air as they hammered wood, silver, bronze, and gold into pillars, posts, basins, and lamps.

Once the completed work was handed over to Moses, only he and the descendants of Levi—God’s chosen priests—could enter the tabernacle. Hereafter, the Israelites were confined to seeing their former possessions and the creations of their hands from the entrances of their tents and in altered form. And yet, this new physical distance heralded a new spiritual and relational intimacy with their God. With God residing in the sanctuary, the Israelites were assured that the divine spirit would accompany them at every stage of their wilderness journey.

Unknown artists :

Booklet with Scenes of the Passion, c.1300–20 , Elephant ivory, polychromy, and gilding

Julia Rooney :

IMG_0320, 2020 , Oil on linen

Mary Roberts :

Hester Middleton, c.1752–58 , Watercolour on ivory

Intimacy and Idolatry

Comparative commentary by Xiao Situ

The installation of the tabernacle marked a new phase in the relationship between God and the Israelites. Formerly, Moses alone spoke with God among the cloud-covered peaks of Mount Sinai, while the rest of the congregation remained encamped below. Through Moses, God communicated his laws and promises to Israel.

Over time, however, the people seemed to yearn for more intimate signs of God’s commitment and constancy, and for more active roles in this divine-human relationship. Perhaps looking to the examples of other kingdoms, the Israelites appeared to long for sturdier structures and greater communal involvement as they struggled to feel like a legitimate nation in the formless wilds of the desert. Their fervent singing and dancing around the golden calf (which they pressured Aaron to sculpt) may have been an expression of their urgent need to relate to the divine in more immediate, embodied, and concrete ways. They wanted to feel nearer to God.

God’s instructions for building the tabernacle answered to this desire. While God supplied the structure’s pattern, all the raw materials used for constructing the sanctuary came from the people’s personal belongings. The making of the tabernacle’s furnishings and utensils required the skill and labour of numerous artisans and craftspeople. In short, the Israelites’ time, talents, and possessions were integrated into this communal structure—the offering of parts of themselves made the structure possible.

The names of the twelve tribes were engraved on the stones set within the priestly breastplates (39:14), ensuring that each time the priests entered the sanctuary, the whole people would be represented upon their chests. The tiny gold bells attached to the hems of the sacred garments tinkled whenever the priests walked, enabling the congregants to hear their movement within the sanctuary. The cloud that hovered over the tabernacle during the day and the fire that lit it up through the night made God’s abiding presence visible throughout the camp. In all these material, sensory, and embodied ways, God ensured that the Israelites felt perpetually connected and engaged in this divine-human relationship.

The three works in this exhibition convey the human desire not only for objects to represent relationships, but also for personal participation in shaping those bonds through embodied ritual or practice. Assurance that one is a meaningful part of a relationship, and that that relationship is substantive and real, seems to require more than spoken promises or symbolic thought—it needs material expression, physical involvement, and creative investment.

The young Middleton cousins probably never met each other—never heard each other’s voices or spent time playing in each other’s company. By commissioning a set of portrait miniatures of the cousins, their parents equipped their children with objects that solicited visual and tactile expressions of attachment and sentiment.

For its owner, the medieval ivory booklet concretized relationship in a slightly different way. Rather than a family member, the relationship offered here was to a communal story, still ongoing, and to a sacred community into which one could be folded through one’s prayers.

Both of these artworks have particular virtues—virtues which the eighth-century monk and defender of icons John of Damascus might have recognized. They draw us into relationship with, rather than being substitutes for, their subjects. Holy images can be useful, John argued, for although they are not divine in themselves, they help people recollect and bring honour to the divine.

This, though, requires discernment. ‘We know what may be imaged and what may not’, wrote John of Damascus (On Holy Images).

Perhaps Julia Rooney was undertaking a comparable sifting in @SomeHighTide. Real and virtual versions of her exhibition coexisted. Both of them offered modes of closeness and connection (the often whimsical locations of the tiny paintings in the gallery space—some nestled above electrical wall outlets near ground level, for example—encouraged visitors to scrutinize them up close). But there seemed a substantial loss in the Instagram version, as the app’s grid format and the strict frontality of the photographs flattened and diminished the paintings’ material bulkiness and organic character.

‘We have passed the stage of infancy’, John of Damascus proclaimed to his eighth-century readers (On Holy Images). We know the difference between what is divine and what is simply a representation of the divine. But the Israelites who had newly arrived in the Sinai Peninsula did not seem to have passed that stage of infancy. And God—having witnessed the people’s worship of the golden calf—knew it. Although Moses had already received the tabernacle plans prior to Aaron’s creation of the golden calf, that tragic incident may have underscored for both God and Moses the importance of the Israelites’ material and physical engagement in constructing the tabernacle. The process would be an object lesson in idolatry, a way to help the Israelites discern the difference between deity and image.

References

Brubaker, Leslie. 2012. Inventing Byzantine Iconoclasm (London: Bristol Classical Press)

John of Damascus. 1898. St John Damascene on Holy Images, trans. by Mary H. Allies (London: Thomas Baker), pp. 8, 19

Commentaries by Xiao Situ