Acts of the Apostles 3

At the Beautiful Gate

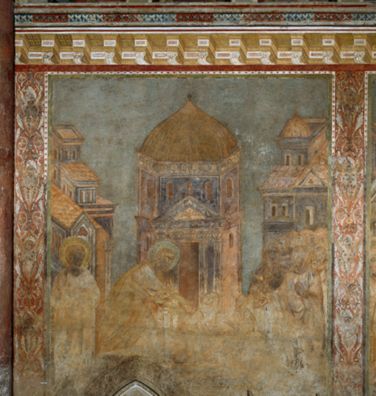

Cimabue

Saint Peter Healing the Lame Man, c.1280, Fresco, Sophie Lunn-Rockliffe; Scala / Art Resource, NY

What’s In A Name?

Commentary by Holly Flora

In the Upper Church of the Basilica of Saint Francis at Assisi, the early Renaissance master Cimabue (c.1240–1302) painted stories of the Apostles, beginning with this scene of Peter Healing the Lame Man from Acts 3. Peter, at the centre of the composition, strides forward, taking the hand of the man, while John stands looking on at left. The lower portion of the painting is damaged, but a second figure can be discerned sitting behind the lame man: probably another beggar. A crowd of bearded men stands to the right, expressing astonishment at the scene.

Cimabue structures and frames his composition via bold and precise renderings of architecture. Two sets of buildings with towers flank the scene, while the Temple in the centre serves to create a tripartite division of the composition. The diagonals of these buildings reach upwards to the outer frame of the image, effectively creating an inverted perspective that projects the figures towards the front of the picture plane. The world of the viewer and that of the Apostles become visually joined via this foregrounding of the protagonists.

This sense of physical place is further enhanced by the specific details that Cimabue includes. The Temple is presented as a hexagonal building with an onion-shaped dome and a pediment with four columns. At the centre of the pediment, Cimabue includes an eagle, the Roman emblem of Herod the Great, mounted on the door of the Temple. The artist therefore seeks to transport the viewer visually through this ‘authentic’ vision of the Holy Land.

In Acts 3:6, the disabled man begs for alms, but Peter states explicitly that he has no ‘silver and gold’, a point relevant to the strict Franciscan prohibition against the friars’ handling of money. Instead, like Peter, the friars for whom this fresco was painted were called to perform their deeds of healing and charity without the exchange of money, drawing only upon the power of the name of God.

Nicolas Poussin

Saints Peter and John Healing the Lame Man, 1655, Oil on canvas, 125.7 x 165.1 cm, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; Marquand Fund, 1924, 24.45.2, www.metmuseum.org

‘Turn again’

Commentary by Holly Flora

Nicolas Poussin (1594–1665) painted this episode from Acts 3 as part of a series of scenes (all showing biblical stories) created in homage to the art of Raphael (1483–1520). Poussin borrows many of the compositional elements and figure types from Raphael’s fresco of the School of Athens in the Vatican, as well as the Renaissance master’s tapestry cartoon of the same subject made for the Sistine Chapel.

Employing a one-point perspective, an artistic technique developed and used extensively during the Italian Renaissance, Poussin shows Peter, with John at his side, at the heart of the scene. They stand at the top of a flight of stairs, while groups of figures placed to the right and left help to create the illusion of three-dimensional space.

The result is a balanced and harmonious painting, yet the impending miracle is almost upstaged by the figures in the foreground. Most of the figures on the right—such as an old and a young man exchanging glances while passing each other, and a woman carrying her purchases in a basket on her head—don’t seem to notice what is happening at the centre. The plight of the poor and sick is seemingly such an everyday occurrence as to escape the notice of most.

Poussin's decision to place the miracle so far back in the composition might be a challenge to us. Is it possible that we might be like these passers-by—able quite easily to overlook the poor and sick (and even the miraculous) if we choose to? Our alternative could be to emulate the awareness of two more exceptional onlookers: the small boy who looks back toward the lame man, and the astonished-looking man just behind him. This man looks across to where, in the left foreground of the painting, a passing nobleman drops a coin into the hand of an emaciated widow, whose baby is shown playfully grasping his own foot.

The man marvels at an act of charitable help. But the fact that the Apostles will not simply help, but actually heal, the lame man means that the boy is about to see something even greater.

Masolino and Masaccio

Peter and John Healing the Lame Man, c.1427, Fresco, The Brancacci Chapel, Santa Maria del Carmine, Florence; Brancacci Chapel, Santa Maria del Carmine, Florence, Italy / Bridgeman Images

‘Look at us’

Commentary by Holly Flora

In the church of Santa Maria del Carmine in Florence’s Oltrarno neighbourhood, the Florentine master Masolino (c.1383–c.1447) and his younger and soon-to-be more famous collaborator Masaccio (1401–28) frescoed a chapel with scenes from the life of Peter. The cycle includes this scene of Peter Healing the Lame Man.

The story in Acts 3 recounts the first miracle that the Apostles perform after the death of Christ. Masaccio depicts Peter and John at the centre of a perfectly balanced composition; at left, the lame man sits with his back to the viewer, reaching up towards Peter, who extends his right hand towards him. As emphasized in the biblical text, John and Peter exchange powerful glances with the beggar (Acts 3:4–5); their eyes meet and the viewer of the fresco prepares to watch the impending miracle unfold.

Masaccio depicts this scene within what would have been for him a contemporary cityscape. Solomon’s portico is shown as a Renaissance loggia; in the background we see palaces with their crenellated walls, wooden balconies, and terracotta roofs. Signs of Florentine everyday life abound: two noblemen strut nearby, their lush brocades and fashionable hats contrasting with the bare feet and heads of the Apostles. A young woman leads her toddler by the hand, laundry hangs drying, and even an intrepid cat prowls outside a window.

Masaccio stages the scriptural narrative clearly and boldly, yet the viewer cannot help but be distracted by the vibrant vignettes of Renaissance urban living throughout the painting. Such a setting would help the viewer to imagine biblical history as part of a continuum with his or her present reality, and serve as a reminder that miracles happen every day, sometimes right under our noses. Or, to echo Peter’s words, ‘in the presence of us all’.

Cimabue :

Saint Peter Healing the Lame Man, c.1280 , Fresco

Nicolas Poussin :

Saints Peter and John Healing the Lame Man, 1655 , Oil on canvas

Masolino and Masaccio :

Peter and John Healing the Lame Man, c.1427 , Fresco

Sensing Salvation

Comparative commentary by Holly Flora

The senses are key to acts of healing as described in the Bible, and in Acts 3, sight and touch in particular are highlighted. The text states that Peter and John first looked at the lame man, and demanded that he look back at them, as a prelude to his healing (v.4). Medieval and Renaissance Christians considered sight the most powerful and primary of the senses, fundamental to the pursuit of knowledge and a prerequisite to belief (e.g. Augustine On Free Will 2.14). Vision was linked to faith in biblical exegesis; therefore, exegetes were naturally drawn to the fact that the cripple is asked to ‘see’ before he is touched by Peter, and only then can he walk. All three paintings of this subject thus underscore the power of the senses.

Via his visual focus on the pairing of John and Peter, Cimabue reinforces the idea that sight and touch are emblematic sensory aspects of the vita mixta practised by the Franciscans, the patrons of this work. Their way of life is a blending of the vita activa (the active life of preaching and service to the poor) with the vita contemplativa (the contemplative life of prayer). John, traditionally read as the visionary Apostle who saw and recorded his vision of the Apocalypse, is frequently cited in Christian exegesis as a model of the vita contemplativa (e.g. Augustine Harmony of the Gospels 1.5; taken up by Aquinas in his prologue to Commentary on the Gospel of Saint John). Sight—including visionary capabilities that take the idea of sight beyond the physical—is therefore John’s purview, and accordingly, Cimabue presents the figure of John to the left of the composition, standing still with his gaze fixed firmly on the eyes of the lame man. Peter, as the Christ-appointed founder of the early Church, was instead emblem of the vita activa, associated with the work of one’s hands, via touch. Cimabue’s mural thus shows Peter, in contrast to John, in motion, striding forward in the act of taking the man by the hand, lifting him up as he is healed.

In Masaccio’s version of the story, our attention is drawn to the mesmerizing gazes of Peter and John by giving them exceptionally wide, dark eyes. Peter stretches his hand toward the lame man and the man returns this gesture, but their hands do not yet touch. We are left to imagine what will happen in the next moment; the viewer therefore becomes a firsthand witness to the precise moment of the miracle. Such a dramatic yet personal presentation is in perfect harmony with the contemporary Florentine setting in which Masaccio sets this scene: an event of the past becomes an event of the present.

The sense of touch is also central to Nicolas Poussin’s rendition of Acts 3. Here, Peter is at the centre of the composition, stretching his open hand toward the lame man, who reaches up with his hand in response, palm down and first finger outstretched. Their gestures intentionally recall the Creation of Adam scene in Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel in the Vatican in Rome. Beyond the artist’s homage to that legendary Renaissance image, this portrayal links Peter’s healing gift to the life-giving power of God. Invoking the senses of sight and touch, John draws our attention to the divine source of the miracle, grasping the lame man’s arm while pointing to heaven.

That all this takes place ‘in the name’ of Jesus Christ (Acts 3:6) suggests that the risen and ascended one is nevertheless still intensely present. But he cannot now be seen except in the forms of the Apostles who speak the words and do the deeds he did. Hence their summons to the lame man to ‘look at us’ (v.4).

And then, in these painted works, a further transposition occurs. The Apostles (and the Jesus they made present at the Beautiful Gate) are made present all over again—this time in paint. This time the summons to the lame man in verse 5 becomes a summons to us, to ‘fix our attention upon them’.

References

Augustine. Harmony of the Gospels. 1888. St Augustine: Sermon on the Mount, Harmony of the Gospels, Homilies on the Gospels, Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers: First Series, Vol. 6, trans. by Philip Schaff (New York: The Christian Literature Company)

______. On Free Choice of the Will. 1993. Trans. by Thomas Williams (Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing), p.57

Thomas Aquinas. 2010. Commentary on the Gospel of John: Chapters 1–5, trans. by Fabian Larcher and James Weisheipl (Washington: Catholic University of America Press)

Commentaries by Holly Flora