1 Corinthians 3:12–15

Purgatory

Juan Cartagena

Ánima Sola (Lonely Soul), c.1900–50, Polychrome wood, 19.1 x 6.8 x 14.4 cm, Museo de Arte de Ponce, Puerto Rico; Gift of Dr Richard E. Nicholson, The Luis A. Ferré Foundation, Inc., 79.1131, Photo: Courtesy of the Museo de Arte de Ponce, Puerto Rico

Between Memory and Oblivion

Commentary by Pablo Perez d’Ors

This small figure conveys the sense of urgency which Paul expresses in his description of a purifying fire and a narrow escape from damnation—it represents a soul pining for release from Purgatory, hands clasped to its chest in a pleading attitude.

Wooden statuettes of a single soul in Purgatory are a typical product of Puerto Rican folk carvers or santeros, whose creations are known locally as santos de palo. Although examples of this iconographical variant from around the 1700s can also be found in the wider Spanish Caribbean, the Puerto Rican case is unique in that the tradition of depicting the ánima sola survived well into the twentieth century.

Objects of this type have often been characterized as folk art, in contrast with those made by professionally-trained artists, which were usually shaped to a greater extent by the weight of conventions and the scrutiny of religious authorities. Owing to the lack of contemporary documentation or artistic literature about them, it is difficult to establish the exact meaning which these carvings held for their original makers and owners.

Traditional santos de palo were made for a domestic context, in which the depiction of a single soul may easily encourage its identification with a departed parent, spouse, child, close relative, or friend. According to some studies in folk religiosity, however, the ánima sola was an invitation to imagine the most forsaken soul of Purgatory, that of an individual whom no one remembers, who is therefore most in need of the viewer’s prayers. Both possibilities attest to the role played by questions of identity in regard to the emotional appeal of images of this kind. In addition, ánimas solas subvert the usual order in that they represent someone to pray for, rather than gain favours from, unlike other intercessor saints and heavenly benefactors with which it may have shared a home shrine.

All in all, representations of the ánima sola evidence the variety and vitality of artistic responses to the idea of Purgatory generated within the context of a global religion.

References

Netto, Elizabeth, Calil Zarur and Charles Muir Lovell (eds). 2001. Art and Faith in Mexico: The Nineteenth-Century Retablo Tradition (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico) 2001, pp. 232–6, 325

Taylor, René, et al. 1993. Colección de arte latinoamericano/LatinAmerican Art Collection (Ponce: Museo de Arte de Ponce)

Unknown Spanish artist

Shrine of the Souls in Purgatory, c.1700s, Granite and wrought iron, Aedicule: 73 x 52 cm; Grille: 36 x 36 cm, Tui [Pontevedra], Spain; Photo by Pablo Perez d'Ors

A Multi-Layered Realm

Commentary by Pablo Perez d’Ors

The purifying fire discussed by Paul in 1 Corinthians 3, understood as an allusion to Purgatory, was often interpreted in connection with a passage in the Old Testament Apocrypha (2 Maccabees 12:38–45) in which prayers and offerings are made for the benefit of those who died having committed idolatry. In light of the latter passage, it was thought possible to reduce the time the souls of the departed spent in Purgatory by carrying out certain actions, which gave rise to a variety of practices and visual representations.

In Galicia, in the north-western corner of Spain, a particular type of economy between the living and the dead was focused on small wayside shrines dedicated to the souls in Purgatory, such as this one (known as petos de ánimas). Besides reminding passers-by to offer their prayers and votive candles, each peto was also a collection box in which alms for the poor could be collected on behalf of the souls in Purgatory, which also helped their ascent into Heaven. In return, souls liberated from Purgatory would afterwards vouch in Heaven for the good deeds of their benefactors on earth.

This reciprocal aspect of the beliefs surrounding Purgatory is reminiscent of the Roman cult of the di lares, just as, coincidentally or not, the peto de ánimas is similar in appearance to the lararium found in Roman households. A specific sub-type, the lares viales, to which wayside shrines were dedicated, were themselves a Roman translatio, or adaptation, of beliefs held by the local Celtic peoples. Thus, petos de ánimas may be regarded as a fascinating window into a multi-layered past made out of permeable categories, in which each successive belief system finds ways to cohere with its predecessor.

From the earliest medieval examples, depictions of Purgatory often show men and women belonging to different social groups to signify the levelling aspect of death. In its proper context, the small cathedral town of Tui, this shrine is a powerful and somewhat subversive reminder that nobody is free from sin, as the soul in the middle prominently sports a bishop’s mitre.

References

Abad, Rosa Brañas. 2007. ‘Entre mitos, ritos y santuarios: los dioses galaico-lusitanos’, in Los pueblos de la Galicia céltica, ed. by F. J. González (Madrid: Akal), pp. 77–443

Sofroniew, Alexandra. 2016. Household Gods: Private Devotion in Ancient Greece and Rome (Los Angeles: Getty Publications)

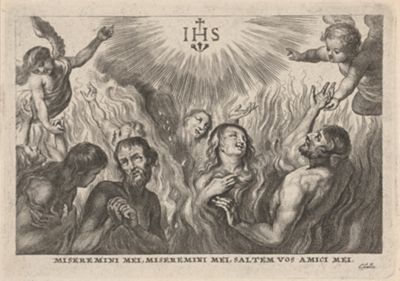

Cornelis Galle I

Purgatory; print after the lower part of the painting by Peter Paul Rubens 'St Teresa of Avila interceding for Bernardino de Mendoza', 1610–50, Engraving, 91 x 128 mm, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam; RP-P-OB-6609, Courtesy Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

Doing Time (after Death)

Commentary by Pablo Perez d’Ors

The several naked men and women in this engraving are depicted as immersed in a fire that ‘will test what sort of work each one has done’, as Paul puts it in 1 Corinthians 3:13.

The lapping flames become confused with the women’s long locks of hair, creating the impression of an indeterminate multitude. Still, each figure has distinctive facial features, indicating that it corresponds to a different individual’s soul. Rather than suffering from the flames, the souls seem to pine for Heaven, represented in the print by the monogram IHS (‘Jesus, Saviour of Mankind’) surrounded by a burst of rays. Two winged children on either side point at the monogram, while simultaneously extending a hand to hoist a soul out of Purgatory and up into Jesus’s presence in Heaven. The souls are literally saved ‘through fire’ (1 Corinthians 3:15).

Flemish engraver Cornelis Galle (1576–1650) envisioned this print after a detail from an altarpiece painted by Peter Paul Rubens between 1630 and 1633, which depicts St Teresa interceding for the souls in Purgatory. The altarpiece, which was originally destined for the church of the Discalced Carmelites in Antwerp and is now in the Koninklijk Museum voor Schone Kunsten, Antwerp (inv. no. 299), was designed to act as a powerful reminder of the ability of certain saints to channel the prayers of the devout and help the ascent of souls from Purgatory into Heaven.

Galle adapted the image by cropping out the figures of Christ and St Teresa and focusing only on the lower section with the souls in Purgatory. On the bottom he added a Latin inscription taken from Job 19:21, which in this context reads as if it were addressed to the viewer by a soul in Purgatory: Miseremini mei, miseremini mei, saltem vos amici mei, ‘Have mercy on me, have mercy on me, at least you, my friends’. This was an image designed to elicit compassion, prayer, and good deeds from those who saw it.

References

Voorhelm Schneevoogt, C. G. 1873. Catalogue des estampes gravées d'après P. P. Rubens (Haarlem: Les héritiers Loosjes)

Juan Cartagena :

Ánima Sola (Lonely Soul), c.1900–50 , Polychrome wood

Unknown Spanish artist :

Shrine of the Souls in Purgatory, c.1700s , Granite and wrought iron

Cornelis Galle I :

Purgatory; print after the lower part of the painting by Peter Paul Rubens 'St Teresa of Avila interceding for Bernardino de Mendoza', 1610–50 , Engraving

Purged Through Fire

Comparative commentary by Pablo Perez d’Ors

A preoccupation with death, divine judgement, and the afterlife has been a characteristic feature of Christianity throughout its history, from its very beginnings. Paul likens death to a fire that comes to test the quality of a building, here a simile for the deeds of the believer. If any of it is found lacking, the builder ‘will suffer loss, though he himself will be saved’ (1 Corinthians 3:15). But (the passage goes on) he will be saved ‘only as through fire’. This fiery imagery opened up a number of enticing theological, as well as visual, possibilities.

Within the Catholic Church, the idea that lesser sins may be purged by fire after death has traditionally been interpreted as support for the doctrine of Purgatory. Though criticized by Protestant Reformers as a superstition with origins outside of Scripture and Christianity, Purgatory enjoyed considerable purchase in Catholic countries, probably owing to its psychological appeal as a plausible intermediate option in the face of Christian eschatology: few people would seem to be so utterly faultless as to go straight into Heaven, or evil enough to deserve eternal damnation in Hell. For that same reason, believers may also have regarded Purgatory as a welcome second chance. It is therefore not surprising that artists and artisans explored this halfway realm in a plethora of different ways across centuries and continents; so much so that images of Purgatory in Western art are arguably as numerous and conspicuous as those of both Heaven and Hell.

A detail of a painting by Peter Paul Rubens, popularized through prints by Cornelis Galle, depicts Purgatory’s most salient feature: its temporary character, which is demonstrated by a human figure, representing one soul in Purgatory, being hauled up into Heaven by an angel. Traditionally, Catholicism also presented this realm in the afterlife as allowing some form of interaction with the living. Through prayers for the souls in Purgatory, which were often addressed to specific saintly intercessors, the devout could effectively help the souls of the dead reach their final resting place in Heaven. By presenting the viewer with this hopeful possibility, the print by Galle helps cement a powerful bond with the dead—the same psychological bond which turned images of Purgatory into desirable commodities.

Neither Scripture nor the teachings of the Catholic Church provided artists with a great wealth of detail as to the state of souls in Purgatory. But the lack of greater definition left open a fertile field for the imagination of artists to thrive, expanding the meaning of Purgatory in different directions.

Rubens and Galle’s Purgatory emphasizes communality, inviting the viewer to envision a multitude of souls scattered in a seemingly vast space. This mass of souls may be reminiscent of another similar thronging multitude in the Christian imaginary—the Communion of Saints.

By contrast, a small Galician shrine made of stone shows only three souls crammed into a tiny aedicule. Rather than its negligible flames, this vision of Purgatory is particularly apt at conveying a sense of the souls’ claustrophobic confinement, which is enhanced by the decorative grille set in front of them.

Finally, across the Atlantic, in Puerto Rico, traditional wood carvers emphasized a completely different aspect by depicting a single soul, suggesting not only individuality but also a sense of isolation that adds an original, psychological, dimension to the soul’s penance.

In Puerto Rico, small carvings of a single lonely soul were kept in the home on a dedicated wooden shelf, often in the company of other statuettes of saints, and would be the focus of their owners’ prayers and candle offerings. The same functionality is apparent in the Galician shrine, in front of which are fixed two wrought iron prongs for sticking and lighting thick (and formerly expensive) wax tapers of the kind normally found in a funerary context. However, unlike the domestic setting of its Puerto Rican counterpart, the Galician example is placed outdoors, at a crossroads.

Details such as these could have an unforeseen effect in the ways in which an image (and therefore Purgatory, in our case) was thought of and interacted with.

In its domestic context, Puerto Rican carvings of a single soul seem to invite a sense of ownership as well as identification with an individual—perhaps a close relative who is sorely missed. Nevertheless, Catholic orthodoxy prefers that prayers should be directed at the souls in Purgatory as a group, since it is generally thought impossible to know the fate of individuals (including the viewer) after death. And death is a crossroads for all souls, not just some.

References

Cuchet, Guillaume (ed.). 2012. Le Purgatoire: Fortune historique et historiographique d’un dogme (Paris: Éditions de l‘École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales)

‘The Final Purification, or Purgatory’. 1993. Catechism of the Catholic Church (Vatican: Libreria Editrice Vaticana) http://www.vatican.va/archive/ENG0015/__P2N.HTM

Commentaries by Pablo Perez d’Ors