Isaiah 55

Return Again

Random International

The Rain Room (as installed at Barbican Centre, London) , 2013, Installation, 100 sqm; Photo: Guy Corbishley / Alamy Stock Photo

Weathering the Word

Commentary by Harriet Neale-Stevens

Rain Room is an installation of perpetually falling water through which the viewer is invited to walk. 3D sensors monitor the whereabouts of participants and control the water valves in the ceiling accordingly so that wherever they walk, they remain dry. The viewer is given a false sense of importance, power, and control. In this room, rain responds to humanity.

Despite the playful nature of the experience of this work, Rain Room challenges our experience of rainfall out in the natural world: it questions our ability to control nature and our propensity to live in bubbles of isolated experience, untouched by weather and forces of nature.

This passage from Isaiah likens God’s word to the rain, which follows a continuous cycle of falling and watering. The prophet reminds us of water’s powerful proclivity to find its own course from the heavens to the sea, resisting human diversion and manipulation. The rain comes down from heaven and waters the earth. It enables the growth of crops, seed, and grain for bread before eventually flowing into the sea, and returning to the heavens. ‘My word shall not return to me empty’, says God, ‘it shall accomplish that which I purpose’ (55:11 NRSV); it shall succeed in doing what I sent it out to do. ‘God’s word is a word that does things’ observes Claus Westermann in his commentary on Isaiah 55; with both the rain, and with God’s word, ‘something is effected and achieves its purpose’ (1969: 289).

Some readings of this passage emphasize humanity’s agency in cooperating with God’s word, just as human cooperation is vital in bringing the rain’s work to fruition by harvesting the crops and turning them into food (Sommer 2014: 877). This kind of response and cooperation is simply not possible in Rain Room, where the presence of a human body actually stops the rain from falling.

In the real world, the power and energy of water will still ultimately find their way from the heavens, to the hills, to the sea, and back again, whatever we do to its natural course.

God’s word has that same power and energy. We can attempt to thwart that power. We can subvert its energy for our own gain. But it will always achieve its purpose before it returns to its source in heaven.

References

Sommer, Benjamin D. 2014. ‘Isaiah: Introduction and Annotations’, in The Jewish Study Bible, by Adele Berlin and Marc Zvi Brettler (Oxford: Oxford University Press)

Westermann, Claus. 1969. Isaiah 40–66: A Commentary, trans. by David M. G. Stalker (Philadelphia: Westminster Press)

Jackson Pollock

Summertime: Number 9A, 1948, Oil paint, enamel paint, and commercial paint on canvas, 84.8 x 555 cm, Tate; T03977, © 2020 The Pollock-Krasner Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Bursting Forth

Commentary by Harriet Neale-Stevens

Jackson Pollock took painting in a new and unexpected direction in the 1940s when he began to experiment with ‘drip’ painting. Breaking free from the constraints of the easel and the paint brush, he tacked his vast canvases to the floor of his studio and dripped, splashed, and poured paint onto them in a trance-like state, creating huge abstract patterns of colour and line.

The painting has a life of its own. I try to let it come through. It is only when I lose contact with the painting that the result is a mess. Otherwise there is pure harmony, an easy give and take. (Pollock 1947–48: 79)

As the prophet calls Israel to return to the Lord, he presents them with a picture of redemption: a picture of unbridled joy and freedom, peace, dancing, and song. ‘The mountains and the hills before you shall burst into song, and all the trees of the field shall clap their hands’ (Isaiah 55:12 NRSV). This vision of redemption is synonymous with what Israel’s return from exile will elicit in them—true joy and freedom.

This is the true freedom to which the faithful are called: a world where creation is summoned to a deeper level of communion, where the unexpected bursts forth, and the natural order of things is turned on its head; a Narnian vision of wholeness (Lewis 1955: 97–108) where all creation leaps and sings.

Praise the Lord from the earth … mountains and all hills, fruit trees and all cedars … let them praise the name of the Lord. (Psalm 148:7–13)

In Summertime Number 9A, black figures appear to dance and leap along the length of the canvas, whilst thinner grey lines of paint trace the figures’ exuberant, looping movements. The bright primary colours add to the mood of joy and celebration. This is ‘summertime’ after all; the time for rejoicing and making-merry, the time for carnivals and fairs.

Pollock’s canvas is 5.5 metres long; it hangs like a frieze depicting a great event, and its shape encourages its viewers to walk its length, taking in its energy and rhythm, joining the procession of dancing figures. Pollock gives us a vision of the new creation that the prophet Isaiah longed for God’s people to see; a creation that dances with abandon and bursts with life in the communion and harmony of its creator’s love.

References

Lewis, C.S. 1955. The Magician’s Nephew (London: Fontana Lions)

Pollock, Jackson. 1947–48. ‘My Painting’, Possibilities 1: 78–83; reprinted in Jackson Pollock: Interviews, Articles, and Reviews, ed. by Pepe Karmel (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 1988)

Varnedoe, Kirk. 1999. Jackson Pollock (London: Tate)

Camille Pissarro

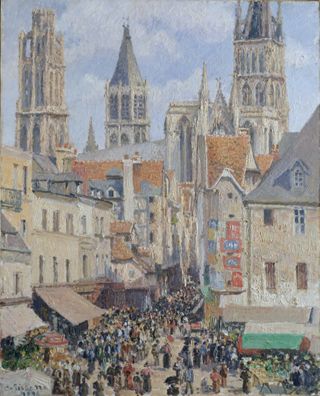

Rue de l'Épicerie, Rouen (Effect of Sunlight), 1898, Oil on canvas, 81.3 x 65.1 cm, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; 60.5, www.metmuseum.org

The Economy of God

Commentary by Harriet Neale-Stevens

Anyone who’s ever been to a busy city market knows the lure of the stalls: rich fare, eye-catching displays, coloured awnings, the smell of food, and the call of the sellers: come and see, come and buy!

In this painting of late-nineteenth-century Rouen in France, crowds gather at the weekly market, held in the streets and square in the shadow of the great cathedral. Engrossed with the toing and froing of city life, local people go about their business, answering the cries of the market sellers with their purchases of food and goods for the week ahead.

The cathedral bells call the crowds to a different economy, however.

Ho, everyone who thirsts, come to the waters; and you that have no money, come, buy and eat! Come, buy wine and milk without money, and without price’. (Isaiah 55:1 NRSV)

A strange cry; and so contrary to the cry of the poor marketeers who need to sell for a good price to make their livelihood. God calls out to the shoppers, in the words of Isaiah, ‘why do you spend your money for that which is not bread, and your labour for that which does not satisfy?’ (Isaiah 55:2 NRSV). True satisfaction and true sustenance lie in God.

Will the crowds make their way through the narrow way to the cathedral to receive God’s free gift of mercy? Will they come to know their place as God’s beloved children, held in the promise of his covenant with David? This chapter of Isaiah reminds the people that when they return to the Lord in penitence they will be empowered: ‘you shall call nations that you do not know, and nations that do not know you shall run to you’ (55:5 NRSV).

Israel will be an agent of the Lord, a voice in the marketplace, calling the people to the delights of God’s rich fare.

Random International :

The Rain Room (as installed at Barbican Centre, London) , 2013 , Installation

Jackson Pollock :

Summertime: Number 9A, 1948 , Oil paint, enamel paint, and commercial paint on canvas

Camille Pissarro :

Rue de l'Épicerie, Rouen (Effect of Sunlight), 1898 , Oil on canvas

New Thoughts and Ways

Comparative commentary by Harriet Neale-Stevens

Isaiah 55 begins with a call to repentance; a call from God to his people Israel to come to him, to listen to him, to return to him. The purpose of this return is so that God can pardon his people, assure them of his faithful promises, and bring them out of exile and back to their homeland, to a place of freedom and joy.

The whole of the passage hinges upon the line, ‘my thoughts are not your thoughts, nor are your ways my ways’ (v.9). God will do something new, something beyond human imagining. The prophet implies that the world’s patterns of thinking and acting could not possibly conceive of God’s methods, which are not constricted by worldly convention, but open up new visions and new possibilities beyond it.

By taking the familiar call of the market seller, who sells his bread for a price, and turning it into God’s call to priceless riches, the prophet Isaiah highlights this incongruity of human and godly thinking.

Pissarro’s painting of the market at Rouen helps us to see the contrast. The cathedral, if read as representing the ways of God, dominates the scene and the vertical draw of its spires and towers lifts our eyes to the sky and to heaven, to things above. The people at the market are tiny in comparison, busy with their buying and selling, enmeshed in their own economic system, unable to break away because they have money to make and mouths to fill. The height of the buildings and the narrowness of the street to the cathedral create the effect of a deep gully which suggests the extent to which humanity is embedded in its own social and economic structures. And yet the presence of the cathedral speaks a different message: that God oversees the market, and continues to call out, offering his own wine, milk, and bread to satisfy the human soul, with no price tag attached.

Isaiah 55 begins a theological reflection in verse 10, showing us that God’s way and his will are to be found in his word. God’s covenant promises are encountered in this word, which goes out from his mouth to achieve its purpose of drawing God’s people back to their creator. The word is like rain—falling and watering the earth and returning to heaven. This is the same water that the prophet calls us to at the beginning of the passage: ‘everyone who thirsts, come to the waters’ (v.1).

Rain Room invites us to come to its waters, but instead of being refreshed we remain dry. The installation plays with our expectations. It gives us a surprise sense of control. We can have authority over the water. Perhaps we enjoy this temporary power that the room grants us. Yet we might wonder how our lives outside the Rain Room are also constrained by our tendency to control. How much of that tendency works in contrary motion to the mission of God’s word? (Humanity’s desire for control was, after all, the problem that emerged in the Garden of Eden, when paradise was lost and humanity’s desire for potency cut it off from God.)

God’s call in Isaiah is to paradise regained (Barton & Muddiman 2012: 479), whether that is of a literal Eden or an Eden-like restoration of Israel’s homeland, city, Temple, and relationship with God. It is a call to a place of beauty and freedom and joy, unmarred by human sin and short-sightedness. Here the mountains will sing and the trees will clap their hands: who could have imagined? The thorn will be replaced by the cypress and the brier with the myrtle—signs of new life in the wilderness, the beginnings of the restoration of the Garden of Eden.

Pollock’s Summertime Number 9A can be seen as a picture of this new life: the paint dances around and about the canvas, in places going off its edge. It was, at its time of execution, a completely ‘new’ sort of image. Pollock’s technique of ‘drip painting’ enacts a freedom comparable to that imagined in Isaiah. Pollock’s subversion of the received order of painting gave rise to a new form of expression and artistic freedom, where the process of painting was as important as the finished product (see Rose 1979).

Pollock famously said of his painting technique, ‘on the floor I am more at ease. I feel nearer, more a part of the painting, … I can … literally be in the painting’(Pollock 1947–48: 79). As he broke with tradition and experienced this new sense of freedom and wholeness in his artistic process so Isaiah’s picture of redemption breaks through human convention, human weakness, and human structures, and envisions a world more lively and true. A world where the unexpected happens, and creation sings God’s word.

References

Barton, John and John Muddiman. 2012. The Oxford Bible Commentary (Oxford: Oxford University Press)

Rose, Barbara. 1979. ‘Hans Namuth’s Photographs and the Jackson Pollock Myth. Part one: Media Impact and the Failure of Criticism’, Arts Magazine 53.7: 112–16

Pollock, Jackson. 1947–48. ‘My Painting’, Possibilities 1: 78–83; reprinted in Jackson Pollock: Interviews, Articles, and Reviews, ed. by Pepe Karmel (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 1988), pp. 17–18

Varnedoe, Kirk. 1999. Jackson Pollock (London: Tate)

Commentaries by Harriet Neale-Stevens