Revelation 19:11–21

The Rider on the White Horse

Unknown artist

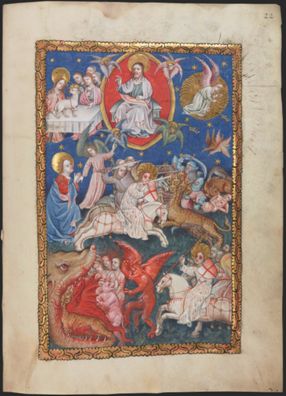

Adoration of Christ; Wedding of the Lamb; Angel calling birds; Fight against the beast; The beast and the false prophet in the fire, from The Flemish Apocalypse (Apocalipsis in dietsch), 1401–1500, Illuminated manuscript, 340 x 250 mm, Bibliothèque nationale de France, Département des Manuscrits, Paris; MS Néerlandais 3, fol. 22r, Bibliothèque nationale de France ark:/12148/btv1b10532634z

The Rider on the White Horse

Commentary by Natasha O’Hear

This striking image brings traditional elements from the visual history of the Rider on the White Horse of Revelation 19 together in a ground-breaking composition.

Hitherto, the narrative of Revelation 19 (the marriage of the Lamb, the descent of the Rider on the White Horse, and the defeat of the Beasts) had been depicted across three separate images. The Flemish Apocalypse devotes just one image to each chapter of Revelation. Each image thus includes several ‘scenes’. Here the marriage of the Lamb (Jesus Christ) to ‘Israel’ takes place in the upper left of the composition (Revelation 19:6–10). The Rider on the White Horse (also Christ in a different guise) adopts a prominent position in the middle register, waging war against the Beast and his army (19:11–19). Christ then returns in the lower register to pursue the Beast and his followers into the hell-mouth, an iconographic shorthand for the ‘lake of fire’ (19:20). John the seer appears to the left of the middle register, gently led by an angel towards these final visions.

This visualization of the Rider is noteworthy for its attention to the detail of the text. The Flemish Apocalypse is known for its use of a striking metallic white paint and this is used to full effect here on both the ‘white horse’ of the Rider and his robe. The robe is streaked with the blood of Revelation 19:13. In keeping with Revelation 19:12, his eyes are flaming and he wears a prominent crown of many diadems. In a visually awkward detail, his sword is held between his lips (19:15, 21; cf. Revelation 1:16).

Condensing the three main narrative blocks of Revelation 19 into one visual space gives this visualization of the closing stages of Revelation an energy and an immediacy lacking in earlier medieval manuscripts. The viewer is swept up into the visual drama unfolding across the three registers, an exciting and unstoppable precursor to the final destruction of Satan/the Dragon and the establishment of the New Jerusalem. This ‘simultaneous’ style of visualization (where what was, is, and will be are shown together) creates a powerful sense of inevitability.

The Many Faces of Christ

Commentary by Natasha O’Hear

The simultaneous style of visualization employed by this unknown Flemish artist not only evokes the deterministic nature of Revelation, but also helpfully allows the viewer to contemplate the different aspects of Jesus Christ that we are presented with in the text.

The dominant image of Christ found in Revelation is that of the Lamb. He is the archetype of passive resistance and of unlikely salvation, first introduced in Revelation 5 and recurring in Revelation 7, 14, and 21–22. The marriage of the Lamb to an ‘Israel’ here read as the Church is depicted in the top left-hand corner of the image. However, as in the central scene in this image, Christ also appears in Revelation 19 (and to an extent in Revelation 1:12–20) as a messianic warrior figure, trampling his victims underfoot. At other points in the text Christ and God use the same language to refer to themselves: ‘the Alpha and the Omega’, ‘the beginning and the end’ (Rev 1:8, 11; 21:6; 22:13), an indicator of Revelation’s very theocentric outlook whereby the distinctions between God the Father and God the Son often appear to have broken down.

No attempt is made by Revelation’s author to synthesize these varied aspects of Christ (that of victim, victor, and God) and broadly this is reflected in this image of the Lamb, God/Christ, and the Rider on the White Horse. The White Horse is more prominent in this image, due to the artist’s faithful adherence to the text but elsewhere in the series the Lamb is clearly the dominant figure. We, the viewer, are therefore left to puzzle over the inconsistences inherent in this trifold presentation of the Christ figure, inconsistencies that the author of Revelation and the Flemish artist were apparently untroubled by.

Meditating on this image could thus become an exercise in contemplating not only the scriptural text, but also the differences between our contemporary interpretative outlook (with our desire to impose rigorous consistency on text and images) and those of our forebears, who were seemingly content to allow the many faces of Christ to exist happily alongside each other.

Irene Barberis

White Horse: And I Saw Heaven Opened (Panel 13), part of The Tapestry of Light, 2017, Tapestry, 304 x 408 cm, On a world tour; © Irene Barberis

The Unstoppable White Horse

Commentary by Natasha O’Hear

In this fluorescent re-envisioning of the fourteenth-century Angers Apocalypse Tapestry, the Rider on the White Horse is given a prominent role. Or to be more precise, the White Horse is prominent and the Rider himself is a more ephemeral figure.

The fourteen-panelled tapestry from which this image is taken (the only known rendering of an entire Apocalypse cycle by a woman) involves the viewer in a multi-sensory experience. As well as encountering the tapestry in a variety of states (via a rotating sequence of ambient light, UV light, and darkness), the viewer is presented with a multi-layered interpretation of Revelation via motifs from many different historical visualizations of the text, as well as from Irene Barberis’s own oeuvre.

Panel 13 is no exception.

Here we see a huge rendering of the White Horse beckoned forth by Sandro Botticelli’s Gabriel (bottom right) and followed by the archangel Michael (Revelation 12). The Rider’s presence is captured solely by his pointing hand (to the left of the Horse’s back) and the blood dripping down the Horse (a reference to Revelation 19:13). Perhaps there is a sense in which the male Rider of Revelation 19 has been unseated or rendered obsolete by the female creator of this series.

While the militaristic male Rider no longer speaks to many of Revelation’s readers, the Horse remains a symbol to which a wide audience can attach hopes and expectations. Thus the vast Horse steps out onto tiny tanks, military jeeps, parachutists: a miniature Armageddon. It is as if they are being swept towards the Hell-Mouth motif in the bottom left-hand corner of the image (taken from the Angers Apocalypse Tapestry).

The texts of the relevant chapters of Revelation are written above the image and when the tapestry is seen in darkness the words glow with phosphorescent light. This is presented as the moment when the heavenly breaks through into the earthly realm, thus ushering in the countdown to the establishment of the New Jerusalem. The comparatively huge White Horse is presented as an irresistible force, flanked by angels, against which human military might is powerless.

Max Beckmann

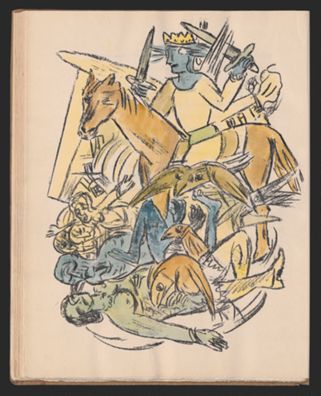

The Apocalypse (Revelation 19:11–16), from Apokalypse, Executed 1941–42; published 1943, Coloured lithograph, 390 x 300 mm, The National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC; Gift of Mrs. Max Beckmann, 1984.64.66, © Max Beckmann Estate, Artist Rights Society, New York/VG Bid-Kunst, Bonn

The Birds and the Bodies

Commentary by Natasha O’Hear

The figure of Revelation 19’s Rider and his Horse is the focal point here. This is fairly typical of Max Beckmann’s approach to Revelation in his series Apokalypse. Throughout his coloured lithographs, Beckmann picks out one or two verses or figures from each chapter to focus on.

Here the Rider is surrounded by his human victims and the birds that devour them (Revelation 19:21). The birds, something of an aside in the text itself, are especially prominent due to their disproportionately large black eyes and angular beaks.

In some aspects, these birds recall an earlier work of Beckmann’s, Bird’s Hell (1937–8), a searing critique of the hellish society created by the Nazis. In Bird’s Hell the birds represent Nazi torturers. Thus, although in this Apokalypse lithograph image the birds appear to be in league with the Rider on the White Horse, there is an ambiguity about them of which the viewer would be wise to be mindful. This intuition is compounded by the fact that the bird at the front centre of the image is possibly feasting on the body of the Whore of Babylon. The semi-nude female certainly bears a resemblance to Beckmann’s ambiguous visualizations of this figure earlier in the series. Perhaps picking up on Revelation 17:16, which deals with the grisly death of the Whore at the hands of the Beast and has given rise to interpretations of the Whore which explore her own victimhood, Beckmann’s half-naked Whore appears to be a victim of sexual violence at the hands of three men.

The potential identification of the Whore of Babylon as one of the Rider’s victims allows the viewer to sense a continuity in Beckmann’s visual narrative which, as here, often seems to dwell on those whom Beckmann perceives to be the text’s real victims.

Necessary Death?

Commentary by Natasha O’Hear

Revelation presents a Satanic consortium which is destroyed by the Rider. However, here we see no sign of the Beasts whom the Rider defeats in Revelation 19:20. In their place are a pile of distorted human bodies, the forgotten collateral damage of the battle of Armageddon. It seems as if the ‘real’ victims are not the members of the Beast’s evil consortium but rather ordinary humans. In terms of Revelation, their deaths are necessary for the establishment of the New Jerusalem but it is fascinating that Max Beckmann draws such attention to them.

The Rider himself bears some of the features of the original text: light radiates from the sides of his eyes, he wears a multi-pronged crown, and he brandishes two swords (although they do not emanate from his mouth). But overall he seems hollow-eyed and rigid, especially in comparison to the fleshly bodies upon which his horse tramples. Is this then a critique of the militaristic side of Revelation? This would hardly be a surprise given Beckmann’s own traumatizing experiences in both the First World War as a soldier and during the Second World War as an exile from his native Germany. His own image of the New Jerusalem, in which an angel wipes tears from John’s eyes, privileges a future reality based not on militaristic victories but on human relationships.

Thus, in some ways this is a confronting image (especially when placed in the context of the entire series) in which viewers are asked to question not only their reading of Revelation but also their own self-understanding, and their own sense of the victim/perpetrator dynamic that this book of the Bible harnesses even while seeking to transcend it.

Unknown artist :

Adoration of Christ; Wedding of the Lamb; Angel calling birds; Fight against the beast; The beast and the false prophet in the fire, from The Flemish Apocalypse (Apocalipsis in dietsch), 1401–1500 , Illuminated manuscript

Irene Barberis :

White Horse: And I Saw Heaven Opened (Panel 13), part of The Tapestry of Light, 2017 , Tapestry

Max Beckmann :

The Apocalypse (Revelation 19:11–16), from Apokalypse, Executed 1941–42; published 1943 , Coloured lithograph

Renderings of the Rider

Comparative commentary by Natasha O’Hear

These three artworks, spanning a time period of over six hundred years, are all taken from Apocalypse cycles. That is, each is part of a rendering of the whole text of Revelation. The Flemish Apocalypse takes a more narrative approach to the source-text, while Max Beckmann focuses in on a few discrete verses from various chapters, and Irene Barberis juxtaposes her own visualizations of elements of Revelation’s text with inherited historical images.

Interestingly, for two images produced in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, both Beckmann and Barberis retain the very text of Revelation as an integral part of their work. Similarly, in The Flemish Apocalypse, each of the twenty-two images appears opposite the corresponding chapter of text.

However, the relationship between text and image differs in each case. The Flemish image serves more as a straightforward illustration of Scripture. This is less a visual commentary and more a visual parallel, with hardly any textual detail left un-visualized, no matter how awkward the result. Such ‘compressed’ visual narrative does nevertheless give rise to an exegetical question, in that it gives the viewer the opportunity to reflect upon the different aspects of Jesus Christ that John presents us with in Revelation (the Lamb, the messianic figure, and the conflation with God the Father). In this image, all three aspects of Christ are unabashedly placed side by side. They are perhaps necessary counterparts to one another, although it is worth noting that it is the Lamb alone who is depicted in the final image of the Flemish series, the New Jerusalem, thus indicating an ultimately privileged position for this figure.

In contrast, Beckmann prioritises particular aspects of the final verses of Revelation 19, and possibly just 19:21. Although the Rider, his horse, and the birds are striking figures, their victims (especially the possible Whore of Babylon figure) are equally visually arresting. Beckmann identified himself with John the seer and also with Revelation’s victims to explore the human cost of Armageddon—something only implied by the text itself—and to further his long-standing critique of the futility of war. In many ways this series therefore represents a questioning—welcome for some—of the rigid certainties of Revelation, with its ‘black and white’ view of the world and of good and evil. Similarly, if the figure at the front of the image is to be interpreted as the Whore of Babylon, then Beckmann is also encouraging us to consider (as some feminist critics of Revelation have done) whether she is as much a victim as a beneficiary of the ‘Beasts’ (she is said to be destroyed by them in Revelation 17:16). Once again, Beckmann appears to be ‘complicating’ Revelation in ways that will be embraced by some and which others will find troubling.

Barberis offers something different again. Although in a very different medium, her work is like the fourteenth-century Angers Apocalypse Tapestry, in that it must be experienced physically, by walking alongside its three-metre-high panels. The experience is less one of intense contemplation in which one is drawn deeply into one image at a time (as with the Flemish and Beckmann images) and more one of full-body immersion in the narrative and themes of Revelation, a sensation compounded by Barberis’s use of different types of light during the viewing experience. Thus, one is asked to consider not just the Rider on the White Horse, here depicted mainly as the White Horse, but how this figure fits within the overall narrative of Revelation. Just as the rendering of Sandro Botticelli’s Gabriel functions in this panel as a forerunner to the White Horse, so the Horse is presented as a necessary forerunner to the New Jerusalem (shown in the final panel), trampling easily over its earthly opponents. Ultimately, it is not the Horse that matters but the reality for which it clears the way.

Just as the Rider himself has been ‘unseated’ by Barberis, so the force of the messianic figure motif (so prominent in the Flemish image) has been erased. Neither the White Horse nor the Rider are really the agents of the establishment of the New Jerusalem; they are merely symbols of its coming. As Barberis herself has said, her Horse and ephemeral Rider represent the breaking of the ‘division of the heavenly and the earthly’ (Barberis and Brown 2017). While in some ways Berberis’s tapestry represents a radical and highly personal reading of Revelation, in this sequence the agency is placed firmly back with God. Albeit in a very different, more provocative way, the deterministic character of Revelation brought out so forcefully in the Flemish images is upheld here too.

References

Barberis, Irene, and Michelle P. Brown. 2017. ‘Tapestry of Light: Intersections of Illumination’. Exhibition booklet.

Camille, Michael. 1992. ‘Visionary Perception and Images of the Apocalypse in the Later Middle Ages’, in The Apocalypse in the Middle Ages, ed. by Richard K. Emmerson and Bernard McGinn (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press), pp. 276–89

Carey, Frances. 1999. The Apocalypse and the Shape of Things to Come (London: British Museum Press)

O’Hear, Natasha, and Anthony O’Hear. 2015. Picturing the Apocalypse: The Book of Revelation in the Arts over Two Millennia (Oxford: Oxford University Press)

Commentaries by Natasha O’Hear