Revelation 13

Beastly Sights

Clarence Larkin

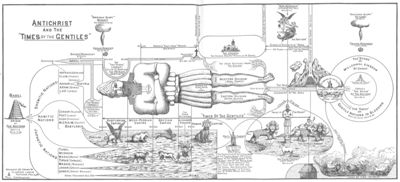

Antichrist and the 'Times of the Gentiles', from Dispensational Truth or God's Plan and Purpose in the Ages, 1920, Print; pp.115–16, Courtesy of the Australian Lutheran College Library

A Schematic of the End Times

Commentary by Andrew T. Coates

Clarence Larkin (1850–1924) was a mechanical drafter and Baptist minister from Pennsylvania. His prophecy charts (of which this is an example) became influential among conservative evangelicals in the twentieth century.

Larkin espoused a theological position called ‘dispensationalism’. Dispensationalists argued that the Bible was a single, coherent narrative of God’s action through time. To understand the hidden meaning of Scripture as a whole, they thought it was necessary to understand how all its smaller, interlocking parts fitted together.

Dispensationalists thought Jesus was going to return soon. While they usually did not set specific dates for the Second Coming, they agreed that it would happen shortly—probably within their own lifetimes. They considered biblical prophecy to be ‘history written in advance’ (Larkin 1920: 5). They used the details of biblical prophecy to understand when and how the world would end.

This chart appeared alongside hundreds of others in Larkin’s book, Dispensational Truth. Its interweaving lines, Bible verse references, and bizarre figures aimed to make Revelation’s hidden meaning visible to the eyes.

Toward the bottom right of the chart stands an image of the ‘man of sin’ (labelled 'Anti-Christ') mentioned in 2 Thessalonians 2:3–10. With small arrows, Larkin connects this image with two others: a horned creature bearing the caption ‘Daniel 7:7–8’ and a leopard-spotted, seven-headed, ten-horned image of the Beast of Revelation 13. In short, Larkin uses these images to argue that all three passages are describing the same figure: namely, the Antichrist, whose appearance on earth will occur just before Jesus returns. This ‘literal’ interpretation erases the distinctions between three very different parts of the Bible.

The chart presents a view of Gentile history from the time of the Tower of Babel to the future Millennial Kingdom of Christ. Its images, lines, and layout are precise—everything appears where it does for a reason. This chart creates a schematic view of the Bible’s relationship to history, and resembles a diagram of an early twentieth-century electrical device, such as a radio or phonograph. A visual map, the chart distills complex information into a densely coded, two-dimensional form.

References

Coates, Andrew T. 2018. What is Protestant Art? (Leiden: Brill)

Larkin, Clarence. 1920. Dispensational Truth (Fox Chase: Clarence Larkin Estate)

Pietsch, B. M. 2015. Dispensational Modernism (New York: Oxford Press)

Joshua V. Himes (printer); Designed by Charles Fitch

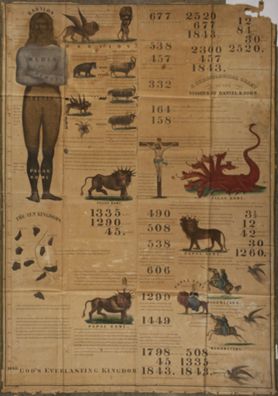

A Chronological Chart of the Visions of Daniel and John (first chart), 1843, Hand-tinted lithograph on cloth, 98 x 140 cm; Photo: Center for Adventist Research

The Mathematical Certainty of the Second Coming

Commentary by Andrew T. Coates

Joshua V. Himes (1805–95) was a publisher and evangelist based in New England. In the 1830s, he became enthralled by the teachings of William Miller, a self-taught Bible interpreter who preached that the world was going to end in 1843.

Miller’s approach to the Bible aimed to harmonize its apparent contradictions. He believed all the events mentioned in the Bible could be placed onto a single timeline. The Bible’s meaning, he insisted, was simple, clear, and straightforward. It seemed otherwise only if improperly interpreted.

As Miller harmonized events in Daniel and Revelation, he came to the startling conclusion that Scripture predicted the future with mathematical precision. Using complex maths and historical thinking in his reading of the biblical text, he calculated that the Second Coming of Jesus would occur between March 1843 and March 1844.

Himes disseminated this lithograph to convey Miller’s teachings as visual fact. Millerites considered the striking visual elements of the chart to be as integral to the meaning of prophecy as the text of the Bible itself. On Himes’s chart, the Beast appears on the far right, beneath the bright red dragon. The text of Revelation 13 surrounds it, reinforcing the notion that this is an obvious, authoritative rendering of what the prophet John saw in the future.

Beneath the Beast appears the caption ‘Papal Rome’. Thus the Beast of Revelation 13 is explicitly equated with the Roman Catholic Church. The calculations and small text beside the image explain how the Beast’s ‘forty-two months’ of blasphemy (Revelation 13:5) referred to 1260 years of uncontested Catholic rule in Rome (a longstanding Protestant assumption). What makes the chart unique is that by connecting the aforementioned 1260-year span to specific historical dates, then applying a mathematical formula, it aims to prove that the Bible predicts Jesus’s return will occur in 1843.

Himes printed thousands of copies of this chart. It became part of the standard kit of Millerite evangelists, who used it while preaching to explain their harmonizing system of interpretation. They thought if people saw this image, they would realize visual truth and find salvation before it was too late.

References

Boyer, Paul. 1992. When Time Shall Be No More (Cambridge, MA: Belknap)

Morgan, David. 1999. Protestants and Pictures (New York: Oxford University Press)

Basil Wolverton

Daniel 7: The Beast with Ten Horns, 2009, Print, Wolverton Bible, Published 2009; Fangraphic books; Image created by Basil Wolverton; Courtesy of Fantagraphics Books (http://www.fantagraphics.com)

The Grotesquery of Literalism

Commentary by Andrew T. Coates

Basil Wolverton (1909–78) was an influential twentieth-century cartoonist. He created some of the most iconic images in the early issues of MAD magazine by rendering the human body in outlandish, bizarre, and warped visual forms.

In the 1940s, Wolverton became active in Herbert W. Armstrong’s Worldwide Church of God. Started as a radio ministry in Oregon and eventually establishing congregations around the world, the denomination became popular for its apocalyptic teachings and ‘plain sense’ approach to the Bible. Armstrong said Jesus would return after a nuclear war between the United States and the Soviet Union.

Wolverton’s creative approach to rendering the human form proved a perfect fit for a form of Christianity convinced of an imminent nuclear apocalypse. His Bible illustrations revel in the melting, twisting, chomping, and other destructive effects that he thought the nuclear end times would have on the human body.

This image of the Beast was first published in the Worldwide Church of God’s denominational journal Tomorrow’s World. It was part of a series of illustrations that accompanied Bible stories for children. The image originally appeared as an illustration of Daniel 7, but in the Worldwide Church of God’s interpretation this was thought to be the same Beast described in Revelation 13 (Armstrong 1952: 6–7).

This image of the Beast permits no abstractions or metaphors. In Wolverton’s reckoning, the prophet travelled to the future and saw a horrible Beast. This image depicts that Beast as a hulking, grotesque lizard-monster. Unconventionally, its ten enormous horns protrude from its back instead of its head. It has four legs on one side of its body, a heavy tail, huge nostrils, and threatening teeth.

This image of the Beast is meant to terrify the viewer. The Beast devours those who are not prepared for the end times. Body parts protrude from the Beast’s teeth. People run away from it with pained, anguished faces. These victims were assumed to be people who had not undergone Christian conversion—those who had not ‘accepted Jesus’ as their personal saviour in an emotional conversion experience. The image suggests that to avoid becoming the Beast’s next victim, a person must accept Jesus right away.

References

Armstrong, Herbert W. 1952. ‘Who is the Beast’, Plain Truth, 17.1: 5–7, 11

Coates, Andrew T. 2018. ‘The Bible and Graphic Novels and Comic Books’, in The Oxford Handbook of the Bible in America, ed. by Paul Gutjahr (New York: Oxford University Press), pp. 451–67

Clarence Larkin :

Antichrist and the 'Times of the Gentiles', from Dispensational Truth or God's Plan and Purpose in the Ages, 1920 , Print

Joshua V. Himes (printer); Designed by Charles Fitch :

A Chronological Chart of the Visions of Daniel and John (first chart), 1843 , Hand-tinted lithograph on cloth

Basil Wolverton :

Daniel 7: The Beast with Ten Horns, 2009 , Print

Seeing Revelation… Literally!

Comparative commentary by Andrew T. Coates

Behold! A Beast with seven heads and ten horns. A horrible Beast who devours. A Beast that looks like a leopard and a lion and a bear. A blasphemous Beast who receives worship from the whole world.

Scholarly consensus holds that in many early Christian communities, Revelation 13 operated as a metaphor, describing contemporary Roman emperor worship as sacrilegious. Informed by this scholarship, many contemporary Christian readers interpret the passage as a warning about the perils of nationalism (DeSilva 2019): a warning against putting loyalty to earthly governments above one’s loyalty to God.

The consensus of scholars is not, however, something that influences the Bible interpretations of millions of Christians today. Many conservative American evangelicals are convinced that the Beast described by Revelation 13 is so bizarrely and horribly explicit that it cannot possibly be metaphorical. To them, this passage of Scripture describes a simple, visible, future reality. Revelation’s Beast is literally a Beast seen by the prophet John in a detailed vision.

Modern scholars often dismiss biblical literalism as the simplistic hermeneutic of the unlearned. This way of interpreting the Bible, however, is much more complex and imaginative than it first appears. It takes significant mental work to put together a coherent vision of the Beast from Revelation’s patchy descriptions. It also takes imagination to apply these ‘literal’ views of the Beast in a way that speaks to everyday concerns.

Since the nineteenth century, an influential segment of American evangelicals have lived as if Jesus will return to earth very soon. These Protestants have outlined the many supernatural events that will precede the Second Coming, such as wars, famines, and earthquakes. They have considered the appearance of the Beast in Revelation 13 to be one moment in this broader sequence of supernatural events leading up to Jesus’s return. Because they have believed that Jesus is coming back very soon, these evangelicals have felt a great urgency to convey their message as quickly and as widely as possible. To help with this, they have often created images of the Beast that appeared in popular charts, journals, and cartoons.

The diagrams and illustrations in this exhibition come from three very different strands of conservative American evangelicalism. Joshua V. Himes (1805–95) followed the teachings of a self-educated prophet named William Miller, who used the Bible to convince thousands of Americans that the world was going to end in 1843. Clarence Larkin (1850–1924) explained how Scripture worked like a machine, believing that if one could understand how the interlocking parts of its timelines fit together, the meaning of the whole would become clear. The cartoonist Basil Wolverton (1909–78) became a follower of a radio preacher who said the world was probably going to end before 1999 in a nuclear war.

American evangelicals were not the first Christians to depict Revelation’s Beast in such visual detail. Christian artists—and Protestants in particular—have a long history of visualizing it. During the Protestant Reformation, for example, Lucas Cranach placed a three-tiered papal tiara on the Beast’s head in his woodcut illustrations of Luther’s German translation of Revelation, turning the Beast into a visual polemic against the papacy (O’Hear 2015: 131–54).

But it is because the three images in this exhibition are not deploying visual art in this metaphorical way that they reveal important features of ‘literalist’ imaginations.

Far from being simplistic or unlearned, these ‘literal’ images are striking not only for their grotesquery, but also for their visual complexity and internal coherence. The works demonstrate the interpretive difficulties evangelicals have overcome by creating pictures of scriptural texts—texts that frequently baffle ordinary thinking.

It takes surprising artistic skill and imagination to create ‘literal’ renderings of the creatures described in the Bible. Those visual renderings then take on immense significance for the interpretive process of these Christians. For them, John really saw a Beast whose physical characteristics conveyed important information about the future apocalypse. So the visual details of artistic renderings mattered. Drawing and viewing these literal images rendered truth for evangelicals so they could see the world through the prophet’s eyes.

While these works reveal much about ‘literalist’ Bible interpretation, it is also important to recognize how they functioned in their original contexts. Nobody contemplated the visual creations of Himes, Larkin, or Wolverton in the disinterested space of a fine art gallery. These images were made into posters, printed in magazines, projected onto church walls, and circulated hand-to-hand as cheap tracts. They served a clear evangelistic purpose. Their goal was to convince viewers to find salvation visually before time ran out.

These three illustrations attempted to convey absolute truth. They were meant to make doubters realize that Jesus was coming back very soon. They were meant to clarify the meaning of a complicated passage of Scripture by making it visible to the eyes. They were meant to scare the hell out of the viewer—literally.

References

Crapanzano, Vincent. 2001. Serving the Word: Literalism in America from the Pulpit to the Bench (New York: The New Press)

DeSilva, David. 2019. ‘Sign of the Beast (Rev 13:11–18)’, www.bibleodyssey.org, [accessed 13 March 2020]

Morgan, David. 2007. The Lure of Images (New York: Routledge)

O’Hear, Natasha and Anthony O’Hear. 2015. Picturing the Apocalypse: The Book of Revelation in the Arts over Two Millennia (New York: Oxford University Press)

Sutton, Matthew. 2017. American Apocalypse (Cambridge, MA: Belknap)

Commentaries by Andrew T. Coates